Interviews

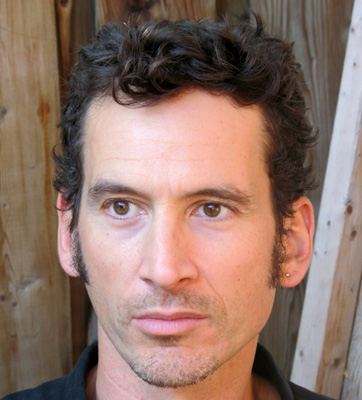

Back Through the Ear’s Narrowed Estuary: Richard Cole in Conversation with Steven Heighton

Steven Heighton talks with Malahat volunteer Richard Cole about "Jetlag" (#171, Summer 2010), winner of the 2011 Malahat Review P. K. Page Founders' Award for Poetry

Steven Heighton talks with Malahat volunteer Richard Cole about "Jetlag" (#171, Summer 2010), winner of the 2011 Malahat Review P. K. Page Founders' Award for Poetry“Jetlag” is set in Arkhangel’sk. What is your connection to this Russian Province that inspired your poem?

The connection is purely imaginative. I've never been to Arkhangel'sk, the city or the province, and I doubt I'll ever go. I did get the idea for "Jetlag" and wrote the first draft while teaching a poetry course in St Petersburg, Russia, and I wrote a second draft on an overnight train heading further north to the small city of Petrozavodsk. But Arkhangel'sk was another night's journey north, just shy of the Arctic Circle, and though I wanted to go, I ran out of time.

So why did I "place" my finished poem, by means of that italicized subtitular line, in Arkhangel'sk in June? To confuse things further, the June part is true--I did experience St Petersburg's annual White Nights fever, squads of revellers roaming the twilit streets at 1 a.m., brandishing magnums of awful Crimean champagne. The setting didn't feel quite right for the poem, so I shifted it two nights' journey north. Mostly it was an intuitive move, but I know I must have been thinking of how the White Nights effect would be even more dramatic up in Archangel--to give the city its anglicized name. Also, Archangel is on the White Sea and I'd have wanted the phantom blankness of that place-name to be an implicit part of the poem's geography. But mainly I think I set the poem there because I've wanted to travel to Archangel ever since seeing it on a map of the Soviet Union in the massive atlas in my father's study.

Like any poet, I love words, and place-names are words with their own inherent poetry--a fact Al Purdy exploited in one of his last poems, "Say the Names," which simply lists, or chants, a string of evocative Canadian place-names. In "Jetlag," the name "Arkhangel'sk" is simply part of the created text--one of those minor creative fibs which, if it works, deepens the truth of the poem or fiction.

And now, in a way, I've been to Archangel.

The poem’s structure reflects the ill effects of transcontinental tourism on the body. Slant rhyme and enjambment, for instance, emulate the speaker’s “body clock” operating out of joint at a “skewed / latitude.” Do you have a philosophical position on poetry’s capacity to facilitate such unique ways of seeing?

Not so much philosophical as technical. What I'd say is that re-enactive techniques--the little tricks and torques by which a poem's word-music and rhythm, punctuation, structure, and layout all embody and re-present their subject matter instead of just describing it--are at the very heart of poetry. They're its staple strategy. When Eric Ormsby describes a rooster's "dark, corroded croak" you hear the bird; when Robert Fagles translates Virgil's evocation of horses whose "galloping hoofbeats drum the rutted plain with thunder," you see them run; in Eunoia, when Christian Bök describes Ubu and Lulu getting it on, the huffing and puffing monosyllables and all the hard and soft "u" sounds serve to . . . well, you get the idea.

These techniques can also be used to represent mental and emotional states--and especially changes in those states, which, I see now, is what "Jetlag" tries to do about halfway through, where the initial structure of repeated quatrains breaks down and the lines and rhythms of the poem open up and loosen.

Like most poets, I use re-enactive prosody partly by instinct in my first drafts, and then in later drafts I elaborate the effects more consciously--or pare them back, if I feel I've gone too far.

The question of travel has been prevalent in your work since your first collection, Stalin’s Carnival. How has your understanding of global mobility advanced as a resource for your writing?

I did most of my growing up in a standard middle-class Toronto suburb, so in a sense I come from nowhere. I have no real--or at least deep--roots in any place that has a distinctive historical identity, culture, or smell. My travels, I see now, have been part of an effort to locate and claim roots elsewhere. It hasn't worked. It never could have. If you're not rooted in a place by a certain (early) age, you'll always be somewhat adrift. I've loved many places where I've lived or travelled, but I'm not truly rooted in any of them. And that's not necessarily a bad thing--not for a certain kind of contemporary writer. (Here I'm going to paste in a few short "memos" that develop this idea; they're part of a collection of memos and short essays coming out in a small edition this fall.)

--27 A scattered, discontinuous life is the postmodern norm; most of us, raised in generic suburbia, come from nowhere; writers of this drifting cohort seek to root themselves in language.

--28 Each book is a room in the home that the rootless writer, the deracinado, seeks to build out of words, images, ideas and narrative.

--29 Deracinados—bred in suburbia, atopia, the generic North American milieu—might as well have been born in cyberspace and raised in the foodcourt of an international airport. Or an Old Navy outlet. If they’re writers, they have one authentic subject: rootlessness. They’ll never have the deep south of Flannery O’Connor, the midcentury "Souwesto" of Alice Munro, the working class New Jersey of Bruce Springsteen, the seething Victorian London of Dickens. Pretending to have a true place they know in a radical, intimate way can result only in frantic mimicry. Their life is a postmodern patchwork and they have no native soil. They can write only of their exile, create books that will be their one home.

“Jetlag” also appears in your most recent collection, Patient Frame. How does the poem fit within the larger conceptual scope of that poetic project as a whole?

Good question. Hard question. I think an objective reader would be better qualified to say what my "conceptual scope" in that book involves. But as I re-enter "Jetlag" now--trying to read it as an outsider--I can see it concerns that search for affiliation that I mention in answer #3. Who feels more uprooted than a jetlagged traveller alone in a mirrorless room in a remote city where few speak his language? So the traveller takes inventory of those things that "rudder [him] / in the real." And he doesn't just list them, he sings them, in the lyric sense of the word: tries to frame them in sensually re-enactive language. So it's not just the cited memories that make a haven for him, it's the actual words used to summon them back: a spell or mantra conjuring a kind of halfway house for lost travellers.

How does that fit into the larger scope of Patient Frame? I can't say for sure, but if I were to read through the book again (don't ask me to do it), I think I'd find many poems trying to trace that same trajectory: from a no-place of disaffiliation to a real place of interconnection.

As both an accomplished poet and novelist, what do you find most demanding and distinctive about your writing process in each genre?

Mostly I funnel my narrative impulses into fiction and my lyrical impulses into poetry--which probably sounds like an obvious point, but I make it to emphasize that I'm not the kind of poet/fiction writer whose novels are as much poem as story, or whose poems are as much narrative as lyric. (Nothing against that stuff--I just don't do it myself.) Still, there is spillover, especially on the level of language. Which brings me to your question.

What's most demanding about the genres? In both cases, getting the words right. But there's a big difference in scale. Poets usually work on the level of the word or syllable, and fiction writers at the level of the sentence, but poets who also write fiction, like me, are saddled with their sensitivity to verbal acoustics; they can't help lugging their loaded poet's-toolbelt into the atelier where they build their stories. So as fiction writers too they work at the level of word or syllable--and they work in that re-enactive micro-manner I describe in answer # 2. Bummer. There are ten thousand syllables in the average story and a few hundred thousand in the average novel.

In a 1997 essay from The Admen Move on Lhasa, you deftly assert, for a new generation of writers, “maintaining a sense of reverence in a world poisonous with chemical and moral toxins demands courage and a kind of inspired obstinacy.” Fourteen years later, does your poetic voice still maintain this tension between skepticism and reverence, between the expanding virtual world and a nostalgic urge to emulate the sensibility of a previous era?

I think it's for a reader to say whether my poems still toy with that tension; I suspect they do, but, again, I'm not the best qualified to comment. What I can tell you is that, yes, I still agree with what I wrote in that essay--though if I expressed the idea now, I'd phrase it in a less pious and self-important tone. I'd also try to be more precise, more specific; "moral toxins" strikes me as a high-minded rhetorical generalization that could mean any number of things.

Two years before that essay collection came out, I published a book of poems called The Ecstasy of Skeptics. It has occurred to me since, while trying to find titles for my two subsequent poetry books, that that first title could work for almost any of my books. (An aside: I suspect that for most poets there is, somewhere out there, a single title that could be applied to most or all of their work.)

I mention the name of that book because of the point you make about maintaining a tension between skepticism and reverence. To me, that's still important--my key balancing act, and not just in the writing but in my life. But I should give a definition of "reverence" in the sense intended in that quote, because it's a risky word to use, a baggage-laden word--a word that many see as a synonym for "piety." I probably shouldn't have used it but I liked the riskiness of the choice, I wanted to be provocative, I wanted to reclaim and rejuvenate the word. In my mind "reverence" still suggests the sense of awe that life should induce in anyone who's remotely attentive; the grateful amazement of those atheists and materialists (some of them great scientists) who are nevertheless essentially religious; the cultivation of a receptive, sensual connection to the physical world.

In part, reverence is what Erich Fromm first called "biophilia."

A last thing. One way of seeing artists is as people who are striving through their work not to be zombified, not to let the daily world transform them into spectres--the spectre being someone whose engagement with life is primarily virtual, objective, mediated, self-conscious. As CBC interviewer Adrian Harewood said recently to a writer who told him his approach to writing was wholly schematic and conceptual, "I think you need to listen to more jazz."

I hope that's what I'm still saying. You need those concepts, but you've got to have the jazz.

* * * * * * * * *

Rich Cole

The P. K. Page Founders’ Award for Poetry recognizes the excellence of The Malahat Review’s contributors by awarding a prize of $1000 to the author of the best poem or sequence of poems to have appeared in the magazine during the previous calendar year. The winner, selected by an outside judge, is announced prior to the publication of The Malahat Review’s Spring issue.