Interviews

Like Showing a Stranger your Self-inflicted Bruises: Tony Tulathimutte on Life after Winning our 2010 Novella Prize

In the spring of 2010, Tony Tulathimutte won our 2010 Novella Prize with his novella, “Brains” (published in issue #171, Summer 2010). His novella was chosen from 196 submissions, and was described by our judges as “not only a compelling, unpredictable story, gripping from beginning to end, but one in which the writer brings authority and authenticity to his use of medical jargon while sending up the protagonist’s sense of her own superiority. The story’s tongue-in-cheek, satiric wit was a welcome change. Above all, the characters are utterly original and stay with the reader after the story ends.” Malahat volunteer Heike Lettrari caught up with Tony recently to question him on life post-win, and his thoughts on the novella.

In the spring of 2010, Tony Tulathimutte won our 2010 Novella Prize with his novella, “Brains” (published in issue #171, Summer 2010). His novella was chosen from 196 submissions, and was described by our judges as “not only a compelling, unpredictable story, gripping from beginning to end, but one in which the writer brings authority and authenticity to his use of medical jargon while sending up the protagonist’s sense of her own superiority. The story’s tongue-in-cheek, satiric wit was a welcome change. Above all, the characters are utterly original and stay with the reader after the story ends.” Malahat volunteer Heike Lettrari caught up with Tony recently to question him on life post-win, and his thoughts on the novella. Where are you now? You recently entered the Iowa Writers’ Workshop—how is that experience impacting your writing? On your website, you state that you’re working on a novel. Is that still the case?

I’m in my second year at the Workshop, living in a second-floor apartment that several of my friends say smells like gas (I can’t smell it). Iowa City is a good place to write, a walkable-drinkable town with weather patterns violent enough keep you indoors and working. I’ve been focusing single-mindedly on my novel since 2008, after finishing “Brains,” an experience that got me comfortable with the idea of writing at somewhat narcissistic lengths about autobiographical material. Right now my novel seems to be running long, but with my deflationary tendencies, I might end up with another novella, who knows.

What did winning The Malahat Review’s 2010 Novella Prize mean to you? Did it change your perception of your own work? And what do you think is the value of a writing contest such as the Novella Prize, which in part seeks to revive and revitalize the quiet form of the novella, as well as promote/reward the writers composing the best of these stories?

The dormancy of the novella form led me to assume that “Brains” wouldn’t see any kind of print, which is fine, since publication should always be an afterthought to the writing itself. Learning that the Malahat Review contest existed was a great surprise, and it struck me as both very generous that a magazine would champion an obscure form, and also very shrewd—after all, there are lots of good novellas looking for publication, and the few places that offer those opportunities are apt to receive a gold-rush of ambitious submissions. You can probably guess how lucky I felt when I learned that I’d won. It’s encouraging and flattering whenever you can convince yourself that other people actually want to read your work, which otherwise feels sort of like showing a stranger your self-inflicted bruises.

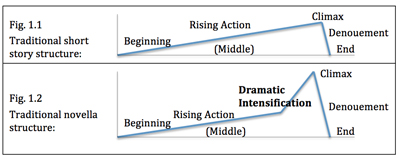

A direct question on form: what, in your opinion, makes the novella? I’ve learned that the classic description of basic short story structure would be something with a beginning, middle, and end, the middle being composed of rising action and a climax, and the end being composed of a denouement or falling action and the end of the story (Fig. 1.1). The traditional novella structure follows a similar pattern, except its middle is notably defined by a sharp rise in dramatic intensification before the climax (Fig. 1.2), arguably to help sustain momentum across the length of the piece. The dramatic intensification is a twist or amplification of tension given the previous array of events. (In comparison to both, novels can potentially go crazy on all form fronts—not that novellas or short stories don’t break from their traditional forms, too). Does this feature make the novella? [Diagram inspired by Steven Price]

I hope I don’t sound wry when I say that the only thing that defines a novella is its length. Length is a complicated topic in fiction, being hazily but strongly bound to what could be called a story’s “size”— i.e., the number of characters, storylines, settings, themes, and the elaborateness of same. This entails a few constraints, but I think narrative forms are generally too broad and malleable to qualify with any specific structure. “The Metamorphosis” is a novella that begins with its climax, for instance. (A lot of Kafka is denouement, actually; flip your novella chart upside-down, that’s a Kafka story.)

Certain trends in publishing are turning in the novella’s favour. It seems that with the industry-wide humbling of big publishers, a lot of boutique publishing houses are getting attention. Melville House is a clear example, and other places like Mark Armstrong’s Longreads site are promoting the 7,500 – 20,000 word length (though I’m irritated that they, like Opium, patronizingly boast the reading durations upfront—7,500 words = 45 minutes, etc., as if we’d only bother reading if it fit neatly into our schedule). And whatever your opinion of e-readers, they have opened up a way to price and publish writing irrespective of length. I hear that Amazon does very well on its sales of longform fiction through the Kindle. Of course, people are going to steer clear of the unhip word “novella,” with its rarefied and suspiciously continental overtones—“longreads” appears to be the term with the most momentum behind it right now, though I sort of hate it, and it also raises the question of why a novel isn’t called a “megalongread,” or an “interminableread,” or whatever.

When writing novellas, what determines an idea’s best length in form? How do you (or did you, for “Brains”) figure that the “appropriate” form for a story is a novella, as opposed to a short story or something much longer? Did the story come first, and form follow? Or form first, and the story expanded into it? Brains is structured in 8 numbered and titled parts – did it start that way, or was this a more superficial addition in later drafts that assisted the story-as-novella in form?

Unfortunately I don’t feel like I have any control at the outset over how long a story will be or what shape it’ll have. What comes first is the idea or the motivation to write something, and when I’ve written a certain amount the form usually becomes obvious. “Brains” was a short story that blimped out to a 200-page novel and then averaged itself out to a 65-page novella. (The novel I’m working on is a compensatory-sounding 800 pages at the moment, and if it doesn’t get shorter I’ll throw myself out of the window I’m staring out of right now.) I gave it the structure it has for a few reasons. Chapterizing a story lets you snip out lots of the dramatically pointless connective tissue that might be expected out of a continuous linear narrative, which was useful for “Brains” since it spans such a long stretch of time. Keeping a stiff focus on Diana’s experience, instead of wandering afield into other characters, also helped keep things brief.

As I mentioned in my post-win Malahat interview, I did have my favourite novella in mind while I was writing—Tolstoy’s “The Death of Ivan Ilych.” Not only is it divided into chapters and structured around the development of a single character’s life and hamartia, but it takes the same bottom-heavy approach to scenic development: the early life is abbreviated, and later events decelerate into long, intense scenes, which may be what you referred to above as Dramatic Intensification. I wasn’t consciously aping Tolstoy, though I suppose that doesn’t mean that I didn’t.

What’s your top tip for anyone embarking on writing a novella, whether this is a first attempt at the form itself, expanding into a longer form, or challenging themselves to the parameters of a shorter word count?

I think it’s good to have as few preconceptions about your work as possible while you’re writing. Being dead-set on writing a novella before you’ve written anything feels to me like being dead-set on having a male baby—you might end up disappointed for no good reason. The present reality that a novella is by far the hardest form of fiction to commercially publish probably dissuades a lot of people from writing them, which is lame. Stories should be as long as they need to be and as short as they can be.

Then again, I may be legislating from my own shortcomings, because like I said, I don’t know how to bullseye a word count. Before “Brains” I’d never written any fiction longer than 35 pages. To be honest, a lot of times writing just feels like aiming an Uzi in some vague direction and then squeezing the trigger for a year or longer. (How’s that for an American simile.)

* * * * * * * *

The deadline for our 2012 Novella Prize is February 1, 2012.

Check out the guidelines for our 2012 Novella Prize.