Alone in Landscapes: Kara Stanton in Conversation with Kai Conradi

Kai Conradi, whose story "Every True Artist" appears in the Malahat's Autumn 2018 issue, discusses the aliveness of desert landscapes, the importance of alone time, and Lander, Wyoming, in their Q&A with Malahat Review volunteer Kara Stanton.

Kai Conradi is a queer and trans writer from Cumberland, B.C. Kai has been published in Grain and has work forthcoming in Poetry. “Every True Artist” is their first published story.

The desert is all over this story — “flat and colossal.” Have you been before? How did it appear to you as a central figure for the story?

You know, when I wrote that story, I had never really been to the desert. Actually, I rode my bike down the west coast of the states four or five years ago and when I got to San Diego I biked east into the desert briefly, but it was rather creepy and I turned around after a few hours. I had forgotten about that until recently.

When I wrote this story I was feeling a little obsessed with the desert and I think it’s because I saw this photo in the New Yorker of a desert full of blooming flowers and I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I think the article was about how there had been huge wildflower blooms because of some weather thing, and all these people flocked there, and I thought that was an interesting idea—this desert pilgrimage—and I wanted to write about it but because I hadn’t really been to the desert and had never seen desert flowers, I didn’t know if I could do it. When I thought about the desert, I imagined it as being alive and buzzing with energy, and that’s kind of where the story came from. Yula imagines the desert as being alive and when she gets there it seems to not be alive at all, and I thought maybe that could be an experience I would have—that I would go to the desert only to find it flat and dead.

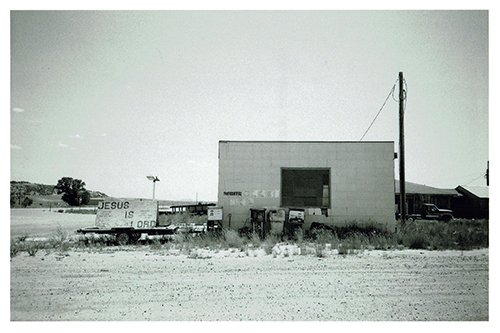

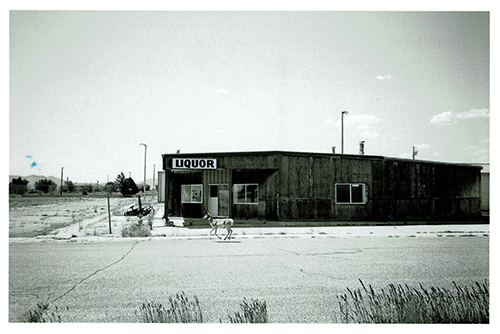

A pretty strange thing happened to me about six months after I wrote this story. I got a job working in the mountains near Lander, Wyoming, and so I drove down there in the spring, and when I got to Lander I felt like I had arrived in the town where "Every True Artist" takes place. It wasn’t quite in the desert but it was very much an old cowboy town with one main street and ranchers walking around in cowboy boots and the buildings looked like something out of a Western. There was this movie store on the corner near the supermarket and on Fridays they would put a karaoke machine out on the sidewalk and if you walked by they’d try to convince you to come sing.

I worked in the mountains for a couple months, leading backpacking trips for teenagers, and then when my contract finished and I got back to town I spent a bit of time staying in this old historic hotel owned by the school I had been working for. The hotel had huge taxidermied cougars and mountain goats and a black bear in the lobby, and the rooms were all different with old Western-style furniture and little mirrors with cacti on the frames and things like that. It was excruciatingly hot outside and I was feeling a bit washed-up and unsure what to do next and I spent some some days sitting around on the carpet of my room in my underwear because it was too hot to do anything, and I thought, “Maybe I should make this into an artist residency.” Only after I had that thought did I realize that I was literally living out the story I had written and that I was becoming Yula! It felt like this strange reversal of “write what you know,” in that in some ways I only came to know the things after I wrote them, but they still turned out to be mostly true. I never did meet a man with a motorcycle out on the highway at night. I got out of Lander pretty soon after my realization.

The poetry infused throughout the piece is totally mesmerizing; it wraps you in a kind of thrumming protective bubble even when the landscape and situation feel pretty desolate. Is that attention to detail and ability to refract it through poetry something you take with you as you interact with new environments? Does it have the power to buffer your experiences?

I’m not sure about the ability to refract environments through poetry, because often I feel like I have no poetry in me, or at least not any that I can put on paper. But I do think that I pay attention to detail wherever I go, and I spend a lot of time looking at the textures of things. When I was in Wyoming, I spent some time in the desert. And it did feel alive, in a way that I found incredibly calming—it is desolate, in a way, but there is also sagebrush everywhere, and you can smell it, and there are tiny cacti with red and yellow flowers and you can hear crickets chirping and sometimes birds calling out. I camped for a few weeks in the desert and I’d get out of my tent early and see the sun rising over this vast flat landscape, and all that dry dirt really did have a kind of energy to it.

I think looking at the textures of any environment—and by that I guess I mean looking at things really closely and for long periods of time and seeing more than just the general outline of a landscape—can be a kind of “protective bubble.” Except that maybe the bubble encompasses the whole landscape and me in it, rather than separating me from the landscape. I think about how I exist in a landscape, or how I absorb any given landscape, and in the desert in particular there is so much dry open space and I have to do something with that space in order to understand it. And most often that something is moving slowly and looking and touching things and just existing with intention. I would also say that this is how I deal with the loneliness that I often feel when I am alone in landscapes that are new and unknown to me: by existing in that loneliness and really trying to take in my surroundings. And often that makes the loneliness feel less lonely and more comforting.

The story presents many different types of portraiture—and failures of portraiture (if that’s not too rude to say)—from Yula’s attempt to draw Doreen, to the unfortunate picture taken of Yula by Rich at the fair, the photos Ribs takes of Yula and Doreen, the ways she tries to capture the desert, and the way in which the story itself depicts Yula. What can we learn from the process of failing to capture someone's image?

I don’t think I know the answer to this question because I don’t know if it’s possible to successfully capture someone’s image. Or rather, I think any image captures something of someone at some point—even Yula’s drawing of Doreen captures something of Doreen, or of that moment, and I’m not sure it’s possible to say whether that attempt is a failure or a success because even if her drawing came out perfect, like a photograph, would that be a success?

Generally, I feel that if I knew the answers to the questions in my stories, then I wouldn’t have to write the stories in the first place. That’s what I like about writing: even after I’ve written out all my questions, their mysteries remain largely unsolved.

In contemplating the desert, Yula reflects that "landscape possesses a kind of aliveness that sometimes shows itself, if you pay close enough attention.” As a writer largely based on the west coast, what does that aliveness feel like here? How is it different?

I would say that the aliveness here is maybe more obvious, in the sense that the “natural” environment is louder, fuller, the trees are bigger and they take up space, the ocean and the wind are noisy and they throw things around and it’s often hard to ignore the landscape. Whereas, to me anyway, landscapes that are more arid and flat and wide-open show that aliveness in different and perhaps subtler ways. The change of the seasons on the west coast also feels very obvious and hard to ignore, whereas I imagine that in places where seasons are less noticeable one might interact with or exist in space in a different way, or maybe at a different rate.

The desert in this story creates the sense of a kind of emptiness that feels so different from the incredibly saturated, technologically-mediated landscapes I move through on the day to day. It makes me think about the quiet we need to create—at first, a space that can feel totally bare and overwhelming, but which can eventually hold a stillness (in the motel’s case, a literal vacancy) that gives us space to focus our attention.

Is this a romanticization of the rural? How do you carve out physical and mental space to focus on your work?

I try not to romanticize the rural in my work though, I think, inevitably I do, because I do feel very attached to the rural. The city, to me, is an exhausting place, and I definitely struggle with the lack of stillness. I think I carve out space by finding places where I can exist in relative stillness. I walk a lot. I spend a lot of time at the beach. And I spend a lot of time in my own head and try to at least find quiet places there, which is difficult sometimes because there is usually a lot of clutter in my brain. I do get out of the city often, and I find that helps. I spend a lot of time alone.

You’re finishing up your undergrad at the University of Victoria. You’re getting published in The Malahat Review & Poetry Magazine. What’s up, bud? What’s next—how’re you feeling?

I feel good! I’m not sure what’s next but I’m also not too stressed about it (yet). I’d like to do an MFA eventually. I’d like to spend more time traveling and existing in unfamiliar places, and put myself in unexpected situations and meet more strange people so I can keep writing stories!

Kara Stanton

* * * * * * * *