Mapping a Woman's Life: John Barton in Conversation with P. K. Page Biographer Sandra Djwa

On January 10, 2013, Sandra Djwa, professor emerita at Simon Fraser University in Burnaby, B.C., will deliver a talk on P. K. Page to mark the third anniversary of the late Victoria poet’s death in 2010. Djwa’s talk, “Finding a Map: Writing a Biography of P. K. Page,” which is presented by The Malahat Review, is UVic's Faculty of Humanities’ first Lansdowne Lecture of 2013. Djwa will speak in Rm. A110, a lecture hall in the A wing of the Social Sciences and Mathematics building on the University of Victoria campus. Doors open at 7:00 pm, with the lecture beginning at 7:30.

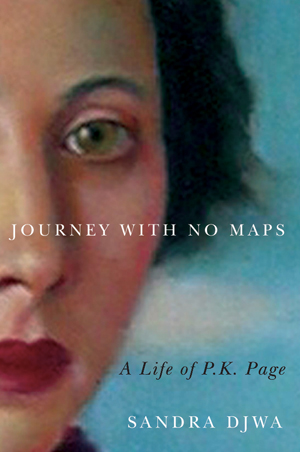

Journey with No Maps: a Life of P. K. Page is Sandra Djwa’s third biography of an important Canadian modernist. This revealing portrait of the late Victoria poet appeared with McGill-Queen’s to wide acclaim in October 2012, and it has recently been long-listed for the 2013 Charles Taylor Prize for Literary Non-Fiction. The UVic Bookstore will have copies of Journey with No Maps for sale at Sandra Djwa’s Lansdowne Lecture.

John Barton, editor of The Malahat Review, interviewed Sandra Djwa by email in December 2012 about biography-making and her fascination with P. K. Page.

What drew you to P. K. Page as a subject for biography? Can you outline in broad strokes the steps you followed to write her book?

I loved her poetry in the old Klinck and Watters Canadian Anthology (Gage, 1955, 1966), especially “Adolescence,” “The Stenographers,” and “Portrait of Marina.” Then, when I began to teach Canadian writing at Simon Fraser University, she gave her first public reading to my students in April 1970. We became friends. Occasionally I would drive her about when she was reading in Vancouver or visit her in Victoria where she once brought me to meet Alan Crawley, the founder of Contemporary Verse.

In December 1996 she invited me to write her biography. The process involved establishing a chronology of her life, collecting her letters and journals from Library and Archives Canada and various other archives, interviewing Page and her friends and relatives, transcribing some early diaries and journals, attempting to establish the chronological order of her poems, and assemble reproductions of her visual art. Detailed studies of her poems, journals, and art soon funneled into an editorial project, The Collected Works of P. K. Page, with general editors Zailig Pollock, Dean Irvine, and Sandra Djwa.

P. K. Page is one of the preeminent poets of her generation. Why do you think this is the case? Can you identify a few poets in later generations whom you feel she’s influenced? How relevant do you think she is to poets starting out today?

She is a fine poetic craftsman with enormous control over the shape, sound, and thought of a poem. Michael Ondaatje once suggested that she is a “poet’s poet” in that many poets look to her for direction. Modernist writers like Margaret Atwood, Phyllis Webb, and Eli Mandel have acknowledged her influence as have a large number of younger writers including Marilyn Bowering and Patricia Young. Between 2000 and 2010 she had a rich correspondence with a wide variety of a new generation of poets, writers, and translators including Susan MacRae and Jaspreet Singh, which suggests they found her work relevant.

You’ve chosen maps—or the lack of them—as a way to understand P. K. as a writer and artist, as a woman, and as a pilgrim on a spiritual quest. Writing a biography is also a kind of journey. How did you come to this understanding of her life?

For a biographer every life is uncharted territory. The usual procedure is to map the terrain with a basic chronology of the life and start from that. But P. K. had something of a phobia about dates and many of her family papers were lost during World War II. This made it essential that I try to sort out the various events and locales of her life.

As I began to put the events of her life in chronological order by searching through various English repositories and her correspondence at Library and Archives Canada, I was struck by the fact that the young Page was continually moving and continually questing—first in New Brunswick when she was first attempting to write (but didn’t know quite how), then in Montreal when she was developing her poetry (she learned by doing), and still later in Brazil when she began to paint (first she worked alone and then she studied with several art teachers). It was in Mexico that her quest for meaning became a life quest with spiritual overtones—she was searching for “a way.” She herself came to believe that the “map” was the right metaphor for her life journey and wrote in 1970, “I am a traveller. I have a destination but no maps.”

Sometimes when writing about or approaching the lives of others, crucial aspects of their stories feel out of sync with our own. As someone with little formal education in spiritual matters beyond Sunday school, I am struck by how fully you’ve investigated P. K.’s attraction to Sufism. Was her spiritual quest something you had to warm to, so to speak, in order to represent it faithfully to readers? Were there any other aspects of her life that you found foreign?

Looking back at my two earlier biographies (The Politics of the Imagination: A Life of F. R. Scott [1986] and Professing English: A Life of Roy Daniells [2002]) it seems to me that both Scott and Daniells, at certain points in their lives, had religious concerns and even spiritual quests. This otherworldly aspect must have resonated with me because otherwise I might not have written about it. But I was brought up as a Newfoundland Methodist and the Sufism of Idries Shah, one of P. K.’s spiritual guides, was far out of my orbit. Nonetheless Sufism was central to her life and work. I was heartened to hear that one reader felt that the structure of the biography reflected a Sufi life because it showed Page making difficult choices based on her inner sense of direction. Similarly, the diplomatic life was foreign to me, as it would be for most readers. Biographers frequently have to move into new territory to present a subject’s life in full.

I understand you are co-editing P. K.’s letters as part of a larger Collected Works of P. K. Page project at Trent University? At what point are you at with this?

I am working with Dean Irvine, the senior editor in this project. We are at the initial stage of checking and adding to the database that I compiled for the biography, approximately 2,000-plus letters. P. K. Page’s letters present real problems because the young Pat tended not to date her letters and the contents of the letters themselves don’t always provide clues for dating. As a result we sometimes have to work with the files of her correspondents that are dated. In addition to scholarly editing, the work yet to be done includes searching for further Page letters. We would be grateful for any Page letters that your readers might be able to contribute.

Journey with No Maps is the third biography you’ve written about an important figure in the Canadian literary world, the other two being on F. R. Scott and Roy Daniells. Are you contemplating writing another biography? If so, who would it be about, and why?

If I wrote another book it might be autobiography. Last month at a launch in Toronto when introducing me, Zailig Pollock suggested my next book should take as subject a young woman who left Newfoundland at nineteen. He had a title as well, “From Sea to Shining Sea,” perhaps only slightly parodic. To some extent I have a unique perspective as I came to B.C. when I was fairly young and established a career that was off-center for the time. Also, I was lucky enough to meet and interview many of the last generation of the older literary figures. The academic profession was still a man’s world—perhaps it still is, to some extent—the new feminism had not quite arrived, and I was teaching at a new university, Simon Fraser, in 1968, two years after it had been founded and before Canadian literature had won respect. It was a rollercoaster for a woman, a Canadian, and a Canadianist.

Most writers acknowledge that writing their books changes them as people, either because their books led to new insights or because they allowed them to articulate a worldview. Is writing a biography any different? How do you feel Journey with No Maps has changed you?

This is my first biography of a woman writer. Writing Page’s life has made me aware of just how difficult it was for a young woman to forge her own path and become a woman of letters in Canada. To some degree she was one of our first real moderns. Writing her life, up to and including her illness and death, has also given me a new sense of the nature of a woman’s life and female solidarity. P. K. Page, artist Jori Smith, Florence Bird (better known as Anne Francis as Commissioner on the Status of Women), and Jean Fraser (wife of journalist Blair Fraser) had a long and nurturing correspondence. Margaret Atwood recognized Page as a progenitor and edited and published her poetry and Page, to some degree, mentored a number of younger writers and scholars including Rosemary Sullivan, Constance Rooke, Marilyn Bowering, and Patricia Young.

John Barton

* * * * * * * *