Hearing Your Own Story:

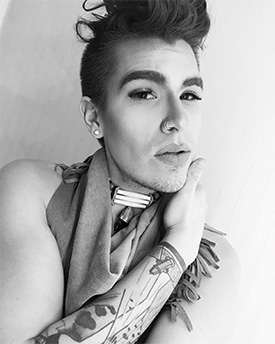

Jake Byrne in Conversation with

Joshua Whitehead

East Coast poet Jake Byrne discusses Indigiqueer identity, community, and non-linearity with Joshua Whitehead, whose short story, “Jonny Appleseed,” appears in the Malahat’s recent Indigenous Perspectives issue.

Joshua Whitehead is an Oji-Cree member of the Peguis First Nation. He identifies as two-spirit (niizh manitoag). He lives in Calgary.

“Jonny Appleseed” opens with the titular character discovering his sexuality through the mediator of HBO’s Queer as Folk, but rejecting that particular vision of queerness sometime after. “You know lattes and condominiums,” Jonny says, “—you don’t know what it’s like being a brown gay boy on the rez,” and it’s true: Jonny isn’t the version of gayness (white, probably monogamous, double-income-no-kids) that you’re likely to see on television. Was the story born with this notion in mind? I know no story has a single ‘seed’ from which it germinates, but was a desire to provide alternatives to this dominant narrative part of your motivation for this story?

Jonny’s birth is an unfortunate one, I think he carries too much with him: anger, hate, loneliness, servility, and perhaps even a dash of sycophancy, but necessity is the most energizing segment of his structuring. He began from a game I used to play reading YA novels, I called it “Where’s We’Wha” and made it my task to find the vanished Indian in every novel. And there is almost always one signifier of Indigeneity in each one, a signifier that worked to transform white settlers into beings with a genealogy, it takes a prehuman to make a posthuman, no? it takes an Indigiqueer to settle queerness. In fact, Robert Bittner wrote about this invisibility in an essay titled “Hey, I Still Can’t See Myself: The Difficult Positioning of Two-Spirit Identities in YA Literature,” He had one thing right: I couldn’t see myself. Not in those YA texts, not in the canon, not in the great majority of books I read through two degrees; hell, even in our own calls for reconciliation there is nothing direct for Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer livelihoods, sexualities, health, hi/stories. Difficult is a precarious word—what’s difficult is not our ontologies, our genealogies, nor our histories; what is difficult is our enforced invisibility from both settler and Indigenous cultural nationalisms. Now I can’t place these into the same camp, for surely they differ for their reasoning, but to say that Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer Young Adult novels are accessible is an understatement. Jonny was born with this weight shackled onto his back. He tells his story unapologetically because he has no other choice, because there is no other story, because there is no other way for him to live. Sex, sexuality, survivance—he is, as Chris Finley wrote in “Decolonizing the Queer Native Body,” bringing “sexy back,” He thinks about sex, he has sex, he is sexed—he makes love to make live—hell, this could be a dinner-time story. If I couldn’t see myself, I thought, well, I’ll write myself into story. I hope you see yourself in there too.

The story seems concerned with fluidity. Every boundary seems just a little bit porous. Lucia, Jonny’s alter-ego, “dies” in the second section, but she is alive and well by the fifth. The chronology of the story itself is a bit slippery. Jonny’s mom swears she’s “not the drink,” as if the drink is a person who takes up residence in her body (which is a sentiment many would recognize, but I digress). Writers tend to spend a lot of time in others’ heads: do you think Jonny’s mom’s advice to find ourselves “a rock and a whole lotta medicine”—something to steady yourself by—holds water for us, too?

The segments I’ve published all dwell around fluids: blood, semen, urine, sweat. Water is ceremony, water is life—we are water. I think of Margaret Laurence here, of old Morag divining on the prairie, her river flowing both ways. Time is like water: fluid, temperamental, lazy at times, charged at another. Time is an NDN too, and “Jonny Appleseed” seeks to play with that—his story is told in Indian Time; every piece of land he sets foot on tells three stories: past, present, future. Jonny cares little for linearity, he lets his body talk every time he fucks; sex is ceremony too. Us NDN’s say “holy hell” a lot and we defer settler colonialism’s fatalism by telling stories aslant, by throwing words into old Morag’s river and saying, “Well ain’t you gonna fish em out?” Jonny’s mom gifts him this strength, if he carries all this weight he needs to stiffen himself like a little NDN-Atlas, for surely he is charting territory too, no? He needs to be like water to fit between the cracks of tectonic plates and canonic borders—that’s how he found you. And that’s the funny thing about rocks, they break apart in the water and in them you find time sediments. Land is ceremony. While “Jonny Appleseed” may not fit one’s expectations of what an Indigenous story sounds like, feels like, looks like—this too is a hi/story of ceremony. Break your rocks, or get them off, and I promise you’ll find medicine.

There’s this notion in many queer circles of “chosen families” —people you aren’t related to by blood but might as well be—and how they can be necessary for a lot of folks in LGBT+ communities. One aspect of this story I found charming is how seamlessly Jonny’s chosen and biological family integrates – the character of Tias is not quite a lover, not quite a brother, the two drawn together because they are “both haunted by ghosts.” Is Tias the rock Jonny needed?

Jonny has beautiful friends who are full of such ugly stories. And perhaps, as you point out, friends is a term that doesn’t work here. His family is large, make-shift, a bricolage even. Tias is a kin who sticks around even as Jonny leaves home, moves away from the rez, as he comes into him self. Jonny needs Tias more than he can know. I’d say that home, for Jonny, is a series of feelings that are sensed through his organs, from tongue to toe and every appendage in between. I wouldn’t say Tias is Jonny’s rock but he is one amongst his rubble—perhaps Tias is more of a rock breaker? He’s the one that breaks Jonny—but he’s the one who ground him, ground him into a medicine.

Let’s talk about the second section. I know in my own work I can struggle to write what I really want to out of fear of reprisal or pushing the envelope too far, but you’ve written about some “difficult” topics in this story and made it look effortless. Any tips for Malahat readers for fearlessness in writing or reading?

Both you and Richard Van Camp have called “Jonny Appleseed” fearless—I’m sure he’d be serving you both some Herbal Essence hair-flip realness right about now. I write this story as a primer on how to have good sex like an article in Cosmo. To be honest, this story terrifies me for two reasons; one, because it’s written in blood; and two, it’s written about blood. I hurt myself writing “Jonny Appleseed.” I write because I need to—because I haven’t ever seen or heard this story before; a story about an Indigiqueer boy who loves himself enough to gift it to others like a medicine bag. I write it because I have queer kin who need stories like this to see themselves within—we need to see ourselves in order to know ourselves. And I write difficultly because I’ve listened fiercely—a good story can reclaim the troubling. I write because I am not an infallible NDN, because Indigeneity is not indemnity, I am not stoic, savage, or noble—though perhaps I’m those adjectives in varying fusions: I can be enduring, aggressive, or proud. I write for the next generation, of which my cousins and niece are a part of, I want them to hear this story, a story of sex-positivity, of sex/uality, of the vivacity and the viciousness of Indigiqueerness, I want them to say “this is enough, this will do, at least for now” during moments of hardship, depression, isolation, seclusion. I write this because I need my Two-Spirit/Indigiqueer kin to survive until the day we build a world for us.

You’ve numbered the sections of this story, which suggests to me there’s more to Jonny’s story than what we’ve seen so far. Do you have plans for a longer work, a novel or novella, continuing Tias and Jonny’s (mis)adventures?

If my long ruminations haven’t been enough, yes! I have been working on “Jonny Appleseed” for the better part of 1.5 years now. He, like Eden Robinson’s Son of a Trickster, began as a short story, then became a novella, and now is nearly formed into a Young Adult novel. The Malahat Review was kind enough to accept the early fibres of this work. Another segment will be published in Prairie Fire this spring. Meanwhile, I am working diligently on finishing this manuscript and letting Jonny prance about the publication industry looking for a home.

Jake Byrne

* * * * * * * *