Issues

Our Back Pages

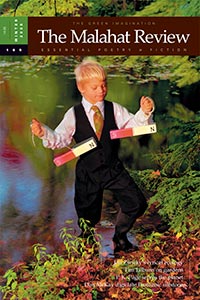

Issue #165

Issue Date: December 2008

Editor: John Barton

Guest Editor: Jay Ruzesky

Pages: 151

Number of contributors: 35

Buy Issue 165: Print Edition

This themed issue of Malahat, The Green Imagination, was co-edited by John Barton and Jay Ruzesky. In his introduction, Barton says the original idea was that it be a celebratory tribute to how writers engage with the British Columbia environment. As submissions began to arrive, however, they realized the overarching vision was more elegiac, more dark than light, and, like the land, did not observe provincial boundaries.

They open with a dedication to Constance Rooke who had recently passed away. She was Malahat’s editor for ten years from 1983 to 1992. Since publication, two of the contributors have also left us—both Connie’s very good friends. P. K. Page, interviewed by Ruzesky in “Serve Your Planet,” and Mike Matthews, a frequent contributor to the Reviews section, and whose review of Laurie Ricou’s, Salal: Listening for the Northwest Understory, is the final one of the issue. So, elegy seems right. Loss is prevalent throughout but there is much to inspire us to action.

Ruzesky’s introduction, “The Y Tree,” recounts a visit he and Tim Lilburn (interviewed in the issue, “The Horse Hitting Its Stride”) had with WSANEC poet Philip Kevin Paul on the lands his family has occupied for generations. Instead of inviting them into his house, he takes them out onto the land and along the ocean shore where he tells them stories and points out plants that continue to be used in traditional ways. Paul makes a comment that sticks for Ruzesky, “You don’t walk in a place when it’s healing.” This is an idea that makes sense and underscores the lack of connection many of our species experience on a daily basis, whether we are aware of this or not. The following lines from Paul’s poem, “Descent into Saanich,” illustrate this well:

The mornings are black well into the steady whir

of traffic—sad machines carrying people,

many who stopped going anywhere long ago.

John Harley’s piece, “Circle of Lakes,” further reminds us, this time with humour, how far some of us have strayed from anything like a close relationship with the natural world. A confirmed urbanite, he finds himself on a canoe trip through the Bowron Lakes. In preparation he “read all the books,” including one called Bear Attacks. And predictably, guess who shows up. Until that point, he had thought of wilderness as vaguely benign, but in the moment experienced it as “malevolent,” and a place with “beasts that want to eat you.” He concludes that wilderness “is a place of many possible places,” both literal and metaphorical.

Carol Matthews, in “The Shadehouse, the Canopy, and the Earthworm,” looks at the idea of transformation in the work of two artists, Emily Carr and Al McWilliams, and the need to go beneath the surface of things. In their work, “we find a quality of interiority that hints at a kind of change that will likely involve not only the transformation of our ‘materials’ but also the transformation of ourselves.” In her essay, “Lyric Realism: Nature Poetry, Silence, and Ontology,” Jan Zwicky posits that “the natural world is an inexhaustible source of meaning, and that, “When we pay attention, we can tell that the world is awake, that it means, hugely and richly, all the time.” In order to “transform” as Matthews suggests, we need “meaning.” In the interview Ruzesky conducts with Zwicky, she refuses “a counsel of despair…. The world, even under threat, is a lyric whole; and opening ourselves to perception of this can heal our culturally fractured psyches.”

Coming back to art and writing and a green imagination, Don McKay (with Ruzesky in “O, The Whole Shebang: An Epistolary Interview with Don McKay”) talks about the fact of human language and our need to “name,” or give a face to things,” which at its best, can be “an act of homage rather than appropriation.” Ruzesky asks him why we bother to write poems about nature, “when none are required for its aesthetic impact to be felt.” McKay responds:

I think this is like asking why silence would not be a more appropriate response than language, in any form. And I guess that my answer is that it would be, especially if we were full-time mystics. But being full-time linguoids, having evolved, since Australopithecus, into big brains with this amazing multi-dimensional, super Swiss Army Knife, it is pure animal pleasure to say something in response to presence. If we say it in poetic, rather than analytic or, possessive modes of language, we’re more likely to be honouring that presence. To be envisaging rather than routinely naming.

Over the course of the issue, certain words or ideas reoccur: attention, presence, meaning, transformation, envisage, imagine. Each contributor to the issue offers insight into how we might imagine our individual and collective transformation. In her poem, “Snowy Owl on a Suburban Street,” Cynthia Woodman Kerkham speaks of, “my bruised home,” and circling back again to “The Y Tree,” and Paul’s understanding that “You don’t walk in a place when it’s healing,” suggests we can use language to heal ourselves and the planet. And as Zwicky says,

The praise song and the elegy are two sides of the same thing and they are annealed. We speak elegies when the thing that materially draws praise from us is gone. It is in this praising and mourning—really experiencing what is, and what is happening—that we begin the reconstructive work of changing the culture.

—Lucy Bashford