Issues

Our Back Pages

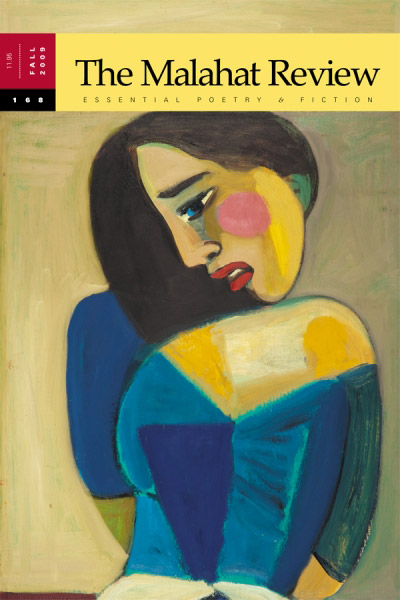

Issue #168

Issue Date: Fall 2009

Editor: John Barton

Pages: 126

Number of contributors: 28

Buy Issue 168: Print Edition

Writers are obsessed with metamorphosis. Moments that transform, moments in which the before is split from the after, in which a life is riven irrevocably. The determination or despair or ambivalence with which characters meet these moments is the meat of a narrative; their reaction is what we as readers relate to, or don’t. A long life is likely to undergo many severings. A short story often undergoes only one.

The fall 2009 issue opens with the winner of the Far Horizons Award for Short Fiction, Eliza Robertson’s “Ship’s Log,” which, in 2014, was published in her critically acclaimed debut collection Wallflowers. In Robertson’s story, the severing has happened even before the first sentence. The death of Granddad is the void at the story’s centre, a hole expressed both symbolically and literally by Oscar’s efforts to escape his grief and the grief of his grandmother by digging his way to China. Oscar’s is one of the usual delusions of anyone who has experienced loss: that perhaps it can be left behind by trading one landscape for another.

Other writers in this issue explore the ways in which living involves a kind of violence: often we have no choice but to be changed. After undergoing a transformation of especial brutality and abruptness, the protagonist in Jackie Gay’s story “The World for a Girl” looks out her window at the landscape of her childhood and considers it “back then in the used to be.” The “used to be” of childhood is evoked more gently, in Ali Blythe’s poem “And the Loons to Haunt and Dive,”by the discovery of an old shirt. In Jeffrey Donaldson’s poem, “Foetal,” an entirely deleted childhood—that of the speaker’s stillborn twin—transforms into a lesson for the living.

Repeatedly, we are reminded that, sometimes, the “before” finds its way into the “after,” and sometimes the imaginary finds its way into reality. In her poem “Road to Viaração, Northeast Brazil,” Jamella Hagen writes, “Present perfect, I say / is for the past whose location in time is / irrelevant.” Time is messy. Eve Joseph imagines the exploits of poems she will never write in “White Camellias”; Susan Gillis describes a storm that closes “the gaps between things”; Ross Leckie observes, “Nothing is in the details because they’re not there” in “On the Porch at the Moment Between Day and Night.” Priscilla Uppal, who died in September of this year, alludes to this disorderliness in her poem “Fortress”: “The universe is up / in a thither, the planets keep slamming / their doors.”

Sometimes we are riven, but more often we are simply cut a little. As readers, we accept this. In the words of Rachel Rose: “I am willing. Wound me.”

—Alana Friend Lettner