Reviews

Poetry Reviews by Jay Ruzesky

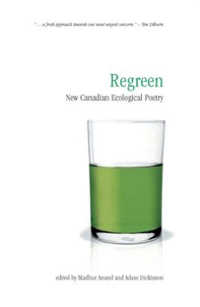

Madhur Anand and Adam Dickinson, Regreen: New Canadian Ecological Poetry (Sudbury: Your Scrivener Press, 2009). Paperbound, 142 pp., $18.00.

Stephanie Bolster, Katia Grubisic, and Simon Reader, Penned: Zoo Poems (Montreal: Signal, 2009). Paperbound, 150 pp., $21.95.

On the train to graduate school through Woodstock in 1988, I realize that what makes the southern Ontario landscape so different from the geography of British Columbia is how purposeful the features of the land are in Ontario. Every tree is planted. Hills have been moved for the highway. Rocks are blasted out of the fields and turned into long stone fences around tony farm houses on the edge of town. Compared to Toronto, what I’m looking at might be “nature” or at least pastoral, but it is not “wilderness” because nothing is “wild.” It is this train tripthat gets me thinking about the relationship between literature and environmentalism.

I arrive in Windsor and the city bus takes me along the edge of the Detroit river. I am fascinated by the flowing water, just as I am fascinated by Detroit. The river is opaque, blue-white like Milk of Magnesia, and rushes by carrying tons of heavy metals from smelters upstream to Lake Erie and beyond. It smells like melted plastic, and fish, what fish there are, reportedly glow. Detroit is a poster boy for the American post-industrial wasteland—T. S. Eliot soaked in battery acid.

These are the early days of acid rain, and in a way, they are also the early days of Canadian Literature. There’s a class in criticism entirely on Margaret Atwood’s Survival. In our writing, the landscape is still something that we either tame or succumb to.

Decades later, the Detroit River is a little cleaner, Acid Rain is a heavy-metal band from Luxembourg, there are courses in environmental studies, and in Canadian literature there are still “progressively insane pioneers,” but now there are also writers who approach the environment and wilderness from diverse perspectives. The compilation of an anthology of Canadian poetry that addresses “nature,” or “wilderness,” or “the environment” is more complex and more urgent.

Madhur Anand and Adam Dickinson, the editors of Regreen: New Canadian  Ecological Poetr have "attempted to interpret the idea of environment broadly.” In his introductory notes, Dickinson points out that the “physical, social, and linguistic environments are all sites of inquiry.” The book is divided into three sections. The first “collects poems overtly engaged with specific landscapes, objects, or phenomena” like Armand Garnet Ruffo’s poem “Ethic” which is a portrait of modern Sudbury:

Ecological Poetr have "attempted to interpret the idea of environment broadly.” In his introductory notes, Dickinson points out that the “physical, social, and linguistic environments are all sites of inquiry.” The book is divided into three sections. The first “collects poems overtly engaged with specific landscapes, objects, or phenomena” like Armand Garnet Ruffo’s poem “Ethic” which is a portrait of modern Sudbury:

The newspaper shows men the size of ants

hanging from scaffolding

as the world’s biggest stack goes up brick by brick.

Proclaiming an end to Sudbury’s infamous reputation

as the dead city of the north, an end to INCO spewing

its yellow poison over the local landscape turning it black.

It is only when we learned the term acid rain

and saw the fish floating belly-up in lakes

hundreds of kilometres away

that we knew the death

had not vanished into thin air

as eagerly announced,

knew it would take a new kind of thinking

that was actually old

ancient.

This poem is at once meditation and argument. It warns against the public-relations spin of industrial companies that have been telling us for years that they’re looking after our interests, and I like the way Ruffo includes his readers in awareness so the poem remains a clear indictment of INCO. He gently hints at the idea that the knowledge of the First Nations was in harmony with the environment. “We knew” the kind of thinking that change requires which means that in some way, we still know.

Also in this section is an excerpt from Don McKay’s “The Muskwa Assemblage.” McKay suggests that the idea of wilderness is “an uninhabited place” within us where “we sense ourselves to be, not masters of creation, not technological wunderkinds, but beings among beings”—a perspective quite at odds with early CanLit theory.

Part two of the book includes poems that are “more actively concerned with the social and built environment” like Sina Queyras’s song to the expressway: “Cloverleaf, Medians & Means” in which she writes:

Beautiful, beautiful the road stretching, birdlike,

yawning from its nest, not all caught up in itself, not

googling itself admiringly, just being its daily self, how we

all ride its coattails.

Section three “collects poems directly engaged with questions of significance and signification in the context of reading and writing the environment.” These are issues that are often at the heart of ecopoetics and emerge out of a fundamental questioning of the practice of writing poetry in the midst of an ecopolitical crisis. Much of this thinking has been addressed by Canadian poets like Tim Lilburn, Jan Zwicky, and Don McKay so it seems curious that they are not included in this section.

One of the qualities of Regreen that I admire is also one of its drawbacks. The book has an agenda—to fill a recognized need for “an anthology of new nature poems” from English Canada, but such a project is, of necessity, a partial answer to a problem. There are too many poets, too many ways of imagining the natural world and argu-ing about what it is to make any one anthology definitive. Regreen is, however, a valuable contribution to the conversation.

Penned: Zoo Poems takes an exploratory approach. The collection hopes simply to  gather poems in English that focus on our “captivation with the worlds inside the cage and out.” The limits the anthologists have set to make the book behave itself are: no prose, just poetry and then only poetry originally written in English; no gardens, just zoos; and no going back too far, just to the opening of the Regent Park Zoo in London in 1828.

gather poems in English that focus on our “captivation with the worlds inside the cage and out.” The limits the anthologists have set to make the book behave itself are: no prose, just poetry and then only poetry originally written in English; no gardens, just zoos; and no going back too far, just to the opening of the Regent Park Zoo in London in 1828.

The result is a quirky and thoroughly interesting collection of poetry that is remarkably diverse given that each of the poems is in some way about the idea of the zoo. One of this book’s strengths is that the poems come from different countries and ages, which makes for curious juxtapositions like Marianne Boruch’s poem “Lunch”:

I was saying consider the metal bars. To keep

such wonders in, to keep us—small wonders—out.

Almost noon, some uniformed someone

turns up with bananas, seeds

fetal pigs, apples, the works. How not

to love this guy?

Opposite Jeni Couzyn’s “Yellow Baboon” which begins:

The yellow baboon

his organ a pink dying stalk

masturbates, legs spread wide

without interest—as one would casually

peel a banana

Another strength of this book is that although it includes some very familiar names: Elizabeth Bishop, Sylvia Plath, Margaret Atwood, Gwendolyn MacEwen, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Wallace Stevens, and dozens of others—the poems represented are often not their most anthologized works so readers can look forward to surprises like e. e. cummings’ “30” with its “little blue elephant” which is “jumbled / to queer this what that a here and / there a peers at you.”

—Jay Ruzesky