Reviews

Fiction Review by Brandon McFarlane

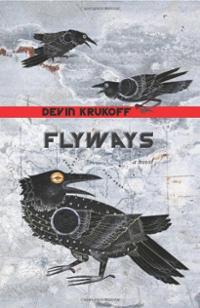

Devin Krukoff, Flyways (Saskatoon: Thistledown, 2010). Paperbound, 267 pp., $19.95.

When one describes fictional characters as “leaping off the page” the cliché generally invokes one of two ideas: either the characters, through their sheer force of presence, leave the reader desiring transcendence, or that the characters are so realistically portrayed that they could seemingly steal your cab or be seen sipping an americano at the local café. The former approach relies upon hyperbole and the reader’s desire that reality should imitate its fictional counterpart. The latter summons the mimetic illusion, manipulating the text’s form to make everything seem realistic. To be successful, both approaches demand a great deal of skill. What astonishes about Devin Krukoff’s Flyways is that it manages to do both. His characters do not “leap off the page,” they reach out and slap you in the face. And this is a good thing.

Flyways can be insufficiently described as a short-story cycle. The text includes thirty-five chapters. Each tells a brief story about a character’s day in an unnamed city. As the narrative progresses, the stories become convoluted as previously mundane acts have an impact upon

other characters. For example, a girl modernizes her grandfather’s farm—installing electricity, a phone, and a TV—and later two hunters caught in a snowstorm seek refuge in the newly renovated house. Similarly, two skydivers who land in the wrong place rescue the third lost and nearly frozen hunter. The joy of coincidence unifies the vignettes advancing the text’s two primary events: the aforementioned blizzard and a domestic terrorist attack on a local Denny’s restaurant. But these plot arches are just that; the events are relatively unimportant. Krukoff’s prose is devoted to his characters.

Flyways employs an interesting conceit: each chapter begins with a flash story about a species of bird. The brief passage and the bird’s implicit characteristics create an elaborate metaphor comparing bird and protagonist. For example, the red-winged blackbird—a creature notorious for thieving shiny-objects—introduces a chapter concerning an autistic boy; the domestic chicken connects to a lady who manically believes in “blue magic.” The blue jay—a bird that devotes itself to a single mate—ironically foreshadows a woman’s gambling addiction. The device is as efficient as it is playful, for it often instantly establishes a character’s essence while also inviting the reader to ponder the metaphor for the chapter’s duration. Some are more successful than

others. I confess that a couple left me confused even after consulting the Internet, which may be a failure of my own imagination rather than the author’s, or may be a geographical constraint, as all the birds are residents of British Columbia.

Krukoff’s delicate balancing of hyperbole and psychological realism is the book’s greatest achievement. Flyways is thematically reminiscent of Zsuzsi Gartner’s All the Anxious Girls on Earth, but without the moral didacticism. While Krukoff’s stories share Gartner’s sense of humour, they elicit the reader’s sympathy rather than condemnation. Many of the characters are extreme: a pregnant teenaged girl tries to abort her child by convincing a stranger to push her down an escalator; a fraudulent therapist prescribes extreme sports to his clients to support his own adrenaline addiction; two ex-cons plan a domestic terrorist attack to unsettle Canada’s commodity fetishism. Despite these sensational situations, Krukoff’s stories remain surprisingly

plausible. He sustains this illusion by manipulating the prose to reflect a character’s psychological state. Indeed, each chapter’s diction and structure mirrors the protagonist’s mental state—a strategy that creates a cast of fully developed individuals. If the character is simple, the sentence structure is simple and the diction limited. If the character becomes horny, sexual innuendo begins to saturate the prose. For example, an ad-man imagines a more successful future while leering at teenaged girls. The italicized words are my emphasis: “Not that his job was without benefits. He was well-liked in the office. He could surf the internet all day long, he imagined, and his position would have still been more secure than some of the executives’. But, at times, he could not help craving more. He wanted to spearhead a winning campaign, to not only be liked but respected by his colleagues, to see his framed portrait hanging outside the boardroom above the Employee of the Month placard.” The device becomes even more tantalizing when Krukoff has the ad-man dismissing the company’s approach that embedded “an ad with innuendo that was not always meant to be consciously detected,” preferring instead ads that are “blatant and crude.” The subtly self-reflexive scene is not only hilarious, but suggests Krukoff’s aesthetic preferences. A realist can get away with fanciful stories if the prose is slyly crafted.

Devin Krukoff won the 2005 Journey Prize for his short story, “The Last Spark.” Flyways affirms his place among Canada’s leading stylists.

—Brandon McFarlane