Reviews

Nonfiction Reviews by Andrew Lesk

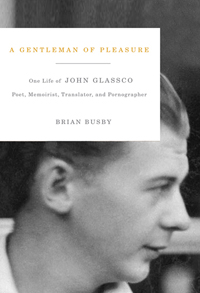

Brian Busby, A Gentleman of Pleasure: One Life of John Glassco: Poet, Memorist, Translator, and Pornographer (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s, 2011). Hardbound, 340 pp., $39.95.

Carmine Starnino, ed., John Glassco and the Other Montreal. Canadian Masters Series, v. 2. (Victoria: Frog Hollow, 2011). Paperbound, 88 pp., $40.

It is nothing less than thrilling—if I may use a word not often associated with Canadian literature—to have two excellent works on (and by) John Glassco appearing in the same year. Is this the (or, another) beginning of a Glassco revival? Let’s hope so. Brian Busby’s remarkably

complete and very readable biography of a somewhat idiosyncratic man of letters brings to the fore Glassco’s many talents, on display not only in his celebrated (and notorious) Memoirs of Montparnasse but also for his less well-known (but equally important) work in the fields of poetry, translation, and pornography. Alongside Busby’s handsomely presented volume, Carmine Starnino focuses on selections of Glassco’s poetic works, which he prefaces with a brilliant and concise introductory essay. For the reader new to Glassco—and to those unfamiliar with his other work—the two books will definitely reward and delight.

Canadian literature—to have two excellent works on (and by) John Glassco appearing in the same year. Is this the (or, another) beginning of a Glassco revival? Let’s hope so. Brian Busby’s remarkably

complete and very readable biography of a somewhat idiosyncratic man of letters brings to the fore Glassco’s many talents, on display not only in his celebrated (and notorious) Memoirs of Montparnasse but also for his less well-known (but equally important) work in the fields of poetry, translation, and pornography. Alongside Busby’s handsomely presented volume, Carmine Starnino focuses on selections of Glassco’s poetic works, which he prefaces with a brilliant and concise introductory essay. For the reader new to Glassco—and to those unfamiliar with his other work—the two books will definitely reward and delight.

But how could someone who writes poetry as (often) defeatist as Glassco’s enchant?  Starnino puts it this way: “Glassco was one of the first Canadian poets to show a sincere interest in decay.” Not for Glassco was the gentle pastoralism evinced by his contemporaries; rather, what he saw evoked, as Starnino rightly puts it, “semidystopian narrative[s].” “A Point of Sky,” “The Burden of Junk,” “The White Mansion”—these, reprinted here along with seventeen others, are “psychodramas” more twisted than Atwood’s survivalist poems; but more so, they herald a new strain in Canadian poetry that turns “pain into art.” What saves Glassco from dismissal is what Starnino calls “a music unfazed by its bleak content.” I wholly agree. Glassco’s theme of a life not wholly lived because it may have passed by is distilled in “A Point of Sky,” where he writes “And you thought there would always be time / …But there is no time.” Yet the poem itself, as a contemplation on missed opportunity constantly pulls away from the murk of pessimism to reveal that indeed there has been time: it is being used to write this very poem which, while it forgoes “the choice of a meadow / Drowsing in a white light of happiness”—a gentle stab at Archibald Lampman’s “Heat”?—embraces words that “burst like blisters in the face of the law / Asserting always it was not made for you.” Starnino, capping an essay that should stand as emblematic of how to write perceptively about a selection of poems, concludes that, with Glassco, “[y]ou came for the style, but stayed for woe.”

Starnino puts it this way: “Glassco was one of the first Canadian poets to show a sincere interest in decay.” Not for Glassco was the gentle pastoralism evinced by his contemporaries; rather, what he saw evoked, as Starnino rightly puts it, “semidystopian narrative[s].” “A Point of Sky,” “The Burden of Junk,” “The White Mansion”—these, reprinted here along with seventeen others, are “psychodramas” more twisted than Atwood’s survivalist poems; but more so, they herald a new strain in Canadian poetry that turns “pain into art.” What saves Glassco from dismissal is what Starnino calls “a music unfazed by its bleak content.” I wholly agree. Glassco’s theme of a life not wholly lived because it may have passed by is distilled in “A Point of Sky,” where he writes “And you thought there would always be time / …But there is no time.” Yet the poem itself, as a contemplation on missed opportunity constantly pulls away from the murk of pessimism to reveal that indeed there has been time: it is being used to write this very poem which, while it forgoes “the choice of a meadow / Drowsing in a white light of happiness”—a gentle stab at Archibald Lampman’s “Heat”?—embraces words that “burst like blisters in the face of the law / Asserting always it was not made for you.” Starnino, capping an essay that should stand as emblematic of how to write perceptively about a selection of poems, concludes that, with Glassco, “[y]ou came for the style, but stayed for woe.”

Busby refashions such woe into an account that reads like the best fiction: it’s that shopworn but appropriate cliché, “un-put-downable.” Who knew that Glassco’s life could be so interesting? But it is. Quite plainly, as Busby states, Glassco was “[n]o trifler, no dilettante, no petit-maître.” His was, and remains, “a most eclectic and unusual body of work.” It is all here: Harriet Marwood, Paris, Kay Boyle, Robert McAlmon, En Arrière, The Journal of Saint-Denys-Garneau, The English Governess, the Foster Poetry Conference, the controversy around Under the Hill, the reworking of Being Geniuses Together. A reading by Margaret Atwood in Montreal results in Glassco’s confession to her that she gave him “a great big erection.” I suspect that many of the delights of Glassco’s life are not known to most Canadians. These two very fine works will, I hope, reintroduce Glassco to a more prominent place in Canadian letters.

—Andrew Lesk