Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Roger Knox

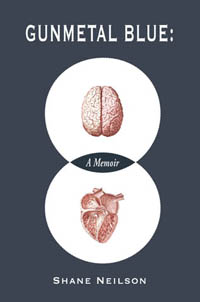

Shane Neilson, Gunmetal Blue: A Memoir (Kingsville: Palimpsest, 2011). Paperbound, 198 pp., $19.50.

Gunmetal Blue is a remarkable memoir of recovery and career development. Author Shane Neilson is a doctor and a poet; from the prologue onwards the two professions intertwine. Somehow the image of Hermes’ staff with two encircling snakes seems a better fit than the onesnaked caduceus of Aesculapius, the symbol of medicine. Medicine is an art as well as a science; nowadays a number of medical journals include poetry. Though their relationship is tricky at times, Neilson makes a compelling case for this pairing.

The opening narrative is a hair-raising account of the author’s

descent into mental illness. While working as an emergency-room

physician, Neilson was concurrently—and obsessively—writing

poems about his alcoholic and abusive father, but was in denial of his

own advancing condition. The crux came with his suicide attempt that

landed him in the same emergency ward where he worked. Now he

observed, as a patient, the modus operandi of his former supervising

doctor. Indeed, occasions for reflection when the tables are turned

pervade this story: doctor as patient, poet as doctor, patient as poet.

The chapter’s title, “Uncle Miltie and the Locked Ward,” alludes to the

latter combination, Miltie being his fellow Maritimer, Milton Acorn.

Acorn’s biography and poetry became Neilson’s comrades in recovery,

on account of Acorn’s honesty, his refusal of electroconvulsive

therapy, and such defiant poems as “I’ve Tasted My Blood,” in which

he vows to surmount dire circumstances, and “I Shout Love,” where

love becomes powerful, abrasive. Neilson came to realize “… that I

was borne aloft by the love I felt for my wife, for my daughter, for

poetry—and something was interfering with the expression of that

love. I was being diverted, I was misguided.” He then writes, “The

best advice is falling away; I’ve fallen / into this fatherhood, able-bodied

but a mind / given to the riven, to the hardy, spare rock / and

peat-black moss” (“Letter to My Daughter”). He needed to get away

from the stark “gunmetal blue” walls of the hospital, and then a timely

parcel arrived: his first published book of poetry; “… years had been

building to this, to the book, and the immediate impact was the cover,

the colour of rusty blood, an earned colour, a colour that also brought

home where paths lead.” He realized that the book “was a portal out

of here.”

Neilson reflects on his gradual recovery in taut, finely-wrought

prose conveying tough-minded thoughts without dwelling on ironies

or gazing in a hall of mirrors (though he does recommend journalling).

He describes his medical residency in an intensive care unit, and his

private practice in a small town. His wife has been an enormous support

to him; family becomes the anchor as he rebuilds his life and

develops a successful career. The chapters become shorter and more

diverse as various pieces of home life, medicine, and poetry are put into

place. Although the pace slackens, this non-linear assembly of elements

gives a more realistic sense of recovery than does, say, the continuous

drama of a TV movie. It reminds us that this is a personal—and literary

and medical—memoir, not straight autobiography.

I am full of admiration for Nielson’s accomplishments, yet at a certain point my views are tested. The author’s outlook is one of intense personalization, needed in recovery when vague generalizations and good intentions are not enough. It involves taking a good look at oneself, building self-acceptance, developing the will to change, and carrying through the recovery process in an ever-widening circle of family, colleagues, and activities. Yet, hard experience shows him that many patients fail to surmount their problems by controlling bad habits or addictions, following diets, or exercising; perhaps because they lack motivation, or a sense of responsibility. My concern is that the author insufficiently acknowledges social factors that may have a negative impact on recovery: lack of income, poor education, decent housing or home care. But maybe that acknowledgment will come, since Neilson does approvingly cite fellow physician-poet Ron Charach’s “Failure to Thrive,” a litany of socio-economic ills and their effects on a baby’s health. One of my favourite chapters is “Letters to Nowlan.” Here Neilson, in the role of a kindly physician, addresses Alden Nowlan, acknowledging the socio-economic woes that Nowlan faced—inadequate medical care, lack of schooling, and poverty— while also pleading with him to stop drinking. Toward the end, a riveting chapter entitled “Profiles” becomes a kind of counterpart to the opening account of Neilson’s own illness, as he applies his insights to a diverse roster of patients. There is a great deal in Gunmetal Blue to recommend, for health professionals and educators as well as a literary readership.

—Roger Knox