Reviews

Fiction Review by Matthew Rutchik

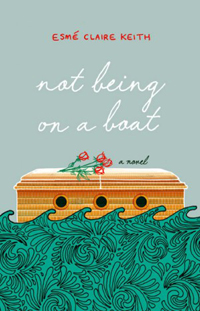

Esme Claire Keith, Not Being on a Boat (Georgetown: Freehand, 2011). Paperbound, 347 pp., $21.95.

Esme Claire Keith sets the tone and pace of her book in the first paragraph:

“There was the press and the crowd and the celebration, like

there should be when a major event is underway, and the launch of a

big new ship is an event.” She introduces her passenger-narrator, Mr.

Rutledge, aboard the Mariola as the ship prepares to set sail, and gives

us a taste of Rutledge’s mostly deadpan tone, modulating from monotonous to emphatic, from blunt to droll. Through this kaleidoscope,

she shows us the atmosphere around the adventure. The people

on the pier “oohed and aahed” at the “luxury and technical achievement”

the ship represents and at the “teams of two, three, or four girls

[who] launched themselves like fireworks” while Rutledge “held his

position at the rail against competition.” Though Rutledge admits he

is “tense and jumpy,” he’s in for a ride.

Esme Claire Keith sets the tone and pace of her book in the first paragraph:

“There was the press and the crowd and the celebration, like

there should be when a major event is underway, and the launch of a

big new ship is an event.” She introduces her passenger-narrator, Mr.

Rutledge, aboard the Mariola as the ship prepares to set sail, and gives

us a taste of Rutledge’s mostly deadpan tone, modulating from monotonous to emphatic, from blunt to droll. Through this kaleidoscope,

she shows us the atmosphere around the adventure. The people

on the pier “oohed and aahed” at the “luxury and technical achievement”

the ship represents and at the “teams of two, three, or four girls

[who] launched themselves like fireworks” while Rutledge “held his

position at the rail against competition.” Though Rutledge admits he

is “tense and jumpy,” he’s in for a ride.

Once the voyage begins, Rutledge is certainly comfortable in his skin. He knows who he is, what he wants and how to go about getting it. “A responsible person,” he says, “checks out his options and test drives people and groups. A good policy is to seek out like-minded people for company and pleasure, although other options are worth considering, like finding people with scarce and valuable goods and services, or better social connections and status.” And Rutledge certainly heeds his own advice. He restrains himself from outlining his concerns to Bud—whose wife, Bailey, “took the right approach” to drinking and waste, and “had a fine ass”—because he doesn’t “like to come off like a rube.” In the Captain’s Mess Rutledge admits he “like[s] to have a personal relationship with the people in charge since [he] always find[s] that keeps service sharp.” When asked by the friendly, opinionated McHughs to spend the day with them at the first port of call, Rutledge thinks of the big picture and appearances: “I was polite and careful not to call him McHuge by mistake. But I said no, obviously, because I didn’t want to be seen with them.”After hearing rumours about the contest winners aboard, he meets them and is “relieved to find out they had money, because if they were poor like people said at Maromed, [he] would have had to cut and run, because it is complicated when you try to be friendly with people from a different tax bracket.”

Though the reader is only privy to what Rutledge discusses, we’re certainly able to see through many of his stories, no doubt because the author leaves no pixel of the picture to the imagination. Around ship staff, Rutledge is the cranky or confrontational consumer who expects satisfaction. Even when his service technician, Raoul, who he warmly refers to as the guy who scrubs the toilet, goes out of his way to make the best of a bad situation, Rutledge manages to lodge complaints. Around fellow passengers, he is the reticent and determinedto- be-agreeable dealmaker. Although his friends are prepared to eat dinner without him, he brings them into his negotiated sweet spot at the captain’s table “to show them what a class act looked like.” The rest of the time Rutledge is in his own head. There, he is crass, candid, and colourful.

Not Being on a Boat is a character-driven book. Much of what Rutledge says and thinks is hard, meant to affect a response. He is a consumer with service expectations in a market economy. He takes for granted that cash is king and feels as if he is the only one who gets this, although, he comes to understand his mistake. When things take a turn for the worse, Raoul arranges a place for him to take cover. There, from inside his spider hole, Rutledge overhears and empathizes with a customer who, when staff want to bring him back to a secure area, stands his ground, saying, “It isn’t what I call all-inclusive.”

—Matthew Rutchik