Reviews

Fiction Review by Jamie Dopp

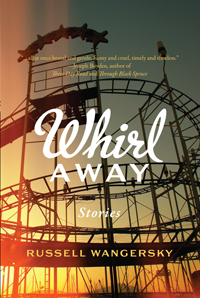

Russell Wangersky, Whirl Away (Toronto: Thomas Allen, 2012). Paperbound, 207pp., $21.95.

Russell Wangersky’s Whirl Away offers twelve stories about characters whose lives are spinning out of control. The stories depict the disorder and grief that results from this and the attempts by the various characters to cope. A number of stories deal with failing marriages. In “Sharp Corner,” we meet John and Mary, a childless couple who live at a sharp bend in a road at which there are a series of car accidents. The story hints early on that there are problems between them. Instead of dealing with these, John becomes progressively more obsessed with the accidents. Talking about them garners him attention at social events and becomes his way of coping with feelings of emptiness. Mary, meanwhile, is revolted. Near the end of the story she says, “I don’t think I can do this anymore,” and it is clear that she is referring to both John’s obsession and to the marriage.

Two of the strongest stories, “Family Law” and “Open Arms,” deal with the failing marriage of a lawyer named Michael Carter. “Family Law” is told from Carter’s point of view. He’s having an affair with a woman in his office and is fearful that his wife has found out—a fear that is realized, in the end, by the delivery of divorce papers.“Open Arms” explores the same situation from Carter’s lover’s viewpoint, and reveals a shocking secret about the origin of the divorce papers.

Other stories examine the coping strategies characters employ in the face of life’s unravelling. Dave, in “The Gasper,” has recurring panic attacks that have him on familiar terms with the 911 dispatcher and ambulance crews. In “McNally’s Fair,” Dennis copes with loneliness by working maintenance at a decaying amusement park, globbing on paint to cover the rust and broken bolts of the park’s main ride, a roller coaster called The Thunder. Like a number of other stories in the collection, these two are told from a slightly detached, thirdperson point of view, which focuses events through the consciousness of the central character while creating an ironic detachment. The effect is to heighten the pathos, I think, for the reader is left to fill in the true horror that the characters themselves are unable to acknowledge.

I was particularly moved by “Echo,” which concerns a five-year-old boy named Kevin, who copes with his abusive father by echoing his father’s abusive language. This is a risky story. Any story from the point of view of a child always risks sounding false or precious—and the subject matter here is especially intense. Wangersky, though, pulls it off by a combination of carefully controlled “off stage” action and the use of third-person point of view.

All in all, this is a very accomplished collection, with some very fine writing. In each story, Wangersky quickly manages to establish his characters and set the action in motion. There is even, occasionally, some sardonic humour to lighten the serious subject matter. When the lover in “Open Arms” thinks about the lawyer “doing the math” on the costs and benefits of his marriage ending and this new relationship beginning, she thinks: “Math happens, and it usually happens when there’s already a fight going on, and by then it’s always too late to redraw the lines.”

As I neared the end of this book, I have to admit, I developed some resistance to the stories. Well-written or not, by the tenth story in which a character was introduced only to show his or her life falling apart, I found myself imaginatively pushing back. Is the whirling apart of a life inevitable? I suspect Wangersky intended to provoke just this kind of questioning. My suspicions are increased by the last story, “I Like,” which introduces a couple in danger of splitting up before it delivers the most unlikely of endings. Even in the midst of life’s whirl, the story suggests, there are, occasionally, small rituals that allow us to hold things together.

—Jamie Dopp