Reviews

Fiction Review by Rachel Rose

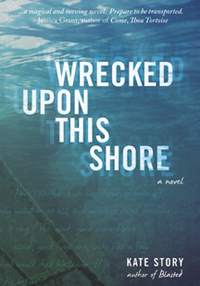

Kate Story, Wrecked Upon This Shore (St. John's: Killick, 2011). Paperbound, 198pp., $19.95.

“I don’t believe this,” I say, as I read Kate Story’s second novel, Wrecked Upon This Shore. “What are the odds?” Friends with whom I share the coincidence shake their heads in sympathetic astonishment. The odds are slim, and yet, it’s happened: I’ve been asked to write a review, the first in years, of a novel that explores abuse, lesbian love, and motherhood, infused by Shakespeare’s The Tempest. And I’m writing my first novel, and it’s also a novel exploring abuse, lesbian love, and motherhood, infused with the spirit of The Tempest. I’m shaken, in the way eerie coincidences can make the ground under one’s feet feel unsteady.

People affected by psychological disorders, whether depression, anti-social behaviour, or narcissism, affect those around them in myriad ways; for an author, this is fertile territory. Ian McEwan’s novel, Enduring Love, is a character study in obsessive personality disorder that makes the reader feel as trapped as the main character. Just as McEwan asks what happens to a man when a chance acquaintance becomes obsessed with him, Story asks what makes people become narcissists.

This novel doesn’t aim for suspense: the author reveals the character Pearl’s death in the first section, and then draws us back to what made Pearl who she was, and how she affected those in her orbit. Pearl draws men and women to her like moths to a flame. From the time we meet her, in high school, she’s already trouble: sexy, fearless, damaged, funny, cruel, and unpredictable. Pearl’s the girl who will take any dare. A girl named Mandy, unfortunately nicknamed Mouse, is drawn in, but as much as Pearl compels, she also burns those who circle her flame. Mouse escapes, but is indelibly marked by her love affair with Pearl. The two meet briefly, years later, when Pearl’s son, Stephen, is four, but their lives diverge until the end. Told in changing points of view, the novel allows us into both Mouse’s and Stephen’s heads, as they try to make sense of loving a narcissist. But there is no sense to be made of loving someone who damages without reason. We don’t really understand how it feels to be Pearl, except through them, and yet she comes through strongly: jagged, compelling, and dangerous. Stephen has grown up believing himself to be unworthy of the unconditional love he never received. In his relationship with the bisexual, polyamorous Laura, he finds solace (her mother is even more of a mess than his) and a curious kind of understanding, but there cannot be real comfort there, as Laura’s determination to reinvent herself, to remain non-monogamous, are too eerily similar to Pearl’s modus operandi. Stephen rejects Laura’s genuine offers to help and care for him as suspect. Despite a connection, their relationship remains troubled, as though, having survived what they have, they are too raw to manage ordinary love; their love affair is another wreck, even as it stands out as the most appealing in the novel.

With its themes of power and control, The Tempest is thematically compelling to Story. Just as Prospero takes his daughter, Miranda, to an isolated island where they live in exile, so Pearl brings Mouse to the island her wealthy family owns (Mandy, of course, is a nickname for Miranda). The play itself is one of the few points of joyful connection between Pearl and Mouse, and later between Pearl and Stephen (named after Stephano, the butler). When Stephen was a child, Pearl read him The Tempest. Before she banished herself, Pearl had her own island, her own fortune, like Prospero. But beyond plot parallels, Story employs lines from The Tempest to illustrate her characters’ moods, as when Stephen brings Laura to meet Pearl and Pearl spits: “Well, here’s my comfort!” Stephen cares for his mother at her worst, as she rages at the world and him. As he copes with her outbursts, he learns what he can withstand, as well as what she had to bear, and what she did to protect him. At the end of her life, Stephen heeds his mother’s wish and calls Mouse, who drops everything, including a not-very-understanding partner, to be with Pearl. Mouse gives Stephen the great gift of knowing that his mother’s narcissism is not his fault. “‘I tell you: it’s always been in her. Not her fault. But there.’ He hears her words and thinks, maybe later I’ll take this in, maybe it will make a difference, later.”

The book hits a rare false note with the imagined scenes of a young girl pushing a baby in a carriage at night, a baby that doesn’t cry. This seems like a dream Stephen would share with his therapist, not part of the novel; we readers get it: the long-suffering Stephen must learn to cry, must learn to voice his needs. Because the novel as a whole is nearly hyper-realistic in its attention to detail and place, the forays into magic realism, while few, are a distraction. Yet, this is a sensitive and thoughtful work. We all know someone like Pearl, someone who is only capable of the kind of love they’ve known, the kind that leaves scars. With Pearl’s death, her son and her almost-lover are left behind to comfort one another. For Pearl, there will be no salvation, no place of peace. But, even as the book ends, with two bereaved and wounded people in an empty house, there is a curious kind of hope implied; as damaged as they are, they are not entirely wrecked upon the shore.

—Rachel Rose