Reviews

Fiction Review by Brandon McFarlane

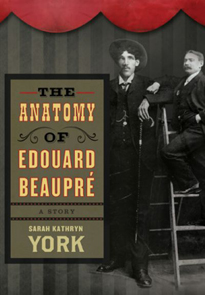

Sarah Kathryn York, The Anatomy of Edouard Beaupré (Regina: Coteau, 2012). Paperbound, 176 pp., $17.95.

Sarah Kathryn York’s The Anatomy of Edouard Beaupré is a solid debut book that recaptures the life of Edouard Beaupré, a world-famous turn-of-the-century giant. A growth on his pituitary gland caused his uncanny power to perpetually grow, but also doomed the man to a short life. After several years working the freak circuit, he died from a combination of lung cancer and tuberculosis at the age of twentythree. York retrieves his story, putting him on display for yet another audience. But her story presents Beaupré as a human, rather than a sideshow attraction, recovering a sense of dignity denied him in life and death. York uses a frame narrative to introduce the story’s major preoccupations. A Montreal doctor works obsessively on Beaupré’s corpse, attempting to discover a cure for hyperparathyroidism, a disease that causes the disintegration of bone mass, the shrinking of the body, and eventual death. He tirelessly examines the corpse, hoping to unlock the secrets behind its unexplainable continual growth, even after death. The doctor’s narrative provides the opportunity to quickly summarize the cadaver’s “life,” if we can call it that, and to introduce readers to the basic facts of Beaupré’s biography. His giantism was a curse that caused him to be exploited and isolated for much of his life. More importantly, however, the opening chapter, “Bones,” establishes the book’s major conceit; each section is named after one of Beaupré’s body parts. Readers, like the many scientists who have dissected the body, learn about Saskatchewan’s “André” by analyzing his scars, organs, and unusual anatomy.

York’s focus on “reading” the body is the text’s most charming element. She reminds us that our bodies carry our histories, but only certain people are able to decode their secrets. In a chapter called “Palm,” a fortune teller seduces Beaupré and attempts to uncover his body’s hidden stories. York writes, “Slowly, the palmist undressed him. Her touch was gentle and cool. As each layer was removed, she unravelled the mystery of his body. She pressed her fingers deep into his skin and along the lines of his bones. What she looked for was the man beneath the specimen, for traces of his past. Death, she was certain, followed Edouard Beaupré.” Like the Montreal doctor, the psychic understands that our skeletons embody our histories. This motif encourages the reader to assume a similar role, York forces her audience to reach out and “read” Beaupré like a poem written in Braille. That is an achievement and she deserves credit for imagining such a “hands-on” role for her audience. A broken nose, like a tattoo, becomes a monument to a story. The conceit loosely structures a narrative that is primarily concerned with humanizing the giant. The Montreal doctor, who narrates the opening and concluding chapters, serves a similar purpose; he publishes an article about how the body may help develop a cure, and includes an extended biography of Beaupré, which, of course, is inappropriate for a scientific journal. This detail draws a parallel between York and the professor, that is, both were attracted to the giant by his freakish appearance but were ultimately seduced by his life. Their retelling of his story seeks to make the ostracized monster a man.

The tantalizing conceit and compelling character study are, however, not enough to sustain the narrative. After reading The Anatomy of Edouard Beaupré, one is left wondering about the point of the story. The plot and narrative arc are underdeveloped. While the chapters do a fine job of adding another dimension to Beaupré’s previously “cardboard” existence, they read more like a compilation of sketches rather than a fully fleshed-out narrative. There is a powerfully sentimental scene that could serve as a climax; Beaupré attends his sister’s wedding and dances with a reluctant young lady. As they spin around the room, he clumsily pulverizes her toes—his feet are gigantic. After the party, he leaves to perform at the World’s Fair, an action that symbolizes his acceptance of his freakish status and his isolation from normal society. He dies shortly after arriving in St. Louis, and his family is too impoverished to have his massive body shipped home. The text seems neither a collection of short stories nor a novel, and does not productively synthesize the genres. Resolving this issue would have unified the narrative; as it stands, the story is structurally incomplete. York also missed the opportunity to write a tragedy. Because it explicitly tells the reader when and how Beaupré will die, the narrative frame invites tragic pathos and allows for dramatic irony. Similarly, Beaupré is alienated and isolated from society. The circus, which he chooses as his final home, provides him with a career but not community; he does not form a fellowship with any of the other acts and the promoters repeatedly swindle the young, naive man. Beaupré’s moment of grace after the dance is certainly touching, but it too strongly contrasts the overwhelmingly tragic details of his biography.

—Brandon McFarlane