Reviews

Fiction Review by Niall McArdle

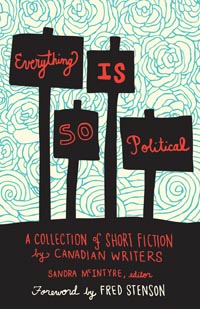

Sandra McIntyre, ed., Everything Is So Political: A Collection of Short Fiction by Canadian Writers (Winnipeg: Fernwood, 2013). Paperbound, 200 pp., $19.95.

Everything Is So Political is a mixed bag of short stories, some marvellous, some forgettable. Reading it is like walking the halls in that first week of university, when you’re bombarded with appeals, from the embarrassingly earnest to the slyly humorous to the downright clever, to join this club or that society. The collection asserts that the political is unavoidable, and its editor, Sandra McIntyre, acknowledges that the title is both a statement of the obvious and a complaint. “Why is everything so political?” Blame George Orwell. Say “political literature” and you immediately invoke his name, for better or worse. While his literary talent was never doubted, he often suffered criticism because his work was seen as just too “political.” It must have bewildered him that Animal Farm, perhaps the most savage piece of satire in English since Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, had been initially rejected by publishers for being too critical of Stalin. Even T. S. Eliot, as far from a Bolshie as you could get, felt the novel was just too negative for a world recovering from the Second World War. It is part of Orwell’s genius that Animal Farm and 1984 have managed to prick at the political conscience of generations of readers while still being successful “literary” novels. Political fiction is notoriously difficult to write: too often the literary shoe is too small for the ideological foot.

It is the irony of our age, when everything was predicted to be post-ideological, an age that was supposed to be about the Global Village getting even smaller, an age when everything is uploaded and shared and instantly commented on, so that people are no longer passive consumers but “citizen journalists,” that there is little in the cultural landscape that can be termed apolitical. When your choice of breakfast cereal, or what car you drive, or which television shows you watch (if you are such a dinosaur that you still have a tv) is a comment on your politics, how can anyone ever hope, as Somerset Maugham did, to simply write “a well-made story”? The good news is that Everything Is So Political contains several well-made stories. Some are subtly political, others wear their ideology on their sleeves, and practically every form of politics is explored, in various settings and genres. In J. Paul Cooper’s “The King’s Nephew,” a couple of war widows get medieval on a nobleman. Orwell makes an appearance, by way of time-travel, in Jack Godwin’s “Gotcha!,” a sci-fi satire on corporate power and political correctness; Michelle Butler Hallett imagines an alternate, non-Canadian Newfoundland in “Lost Wax Casting.” R. Jonathan Chapman’s “The Extremists” is a miniature play—just one scene, really—examining a peculiar case of political-party strategy. One of the outstanding stories in the collection, “Elephant Air,” by Fran Kimmel, examines the topic of animal cruelty in a tender tale of love and loss between father and daughter. The equally powerful “A Year of Coming Home” by A. S. Penne proves what we all know: that the personal is the political.

Two of the stronger stories in the book deal with the culture clash between whites and Natives, and both are downers. Joan Baril’s “Grace Street, 1946” is a coming-of-age tale about tacit segregation and Old Country tribal hatred. In Catherine Brunet’s “Star Spinning,” a white teacher in an impoverished Ojibway community feels she is another in a long line of colonizers. The story contains a line about hypocrisy that is meant to shock: “Canada is the model neighbour that beats his wife when the curtains are drawn.”

There are several shock-factor moments in these stories. Both Shane Joseph’s “Suicide Bombers” and Ethan Canter’s “The Briefcase” deal with terrorist violence, the latter in an alienated, unsettling manner reminiscent of Don DeLillo. Several stories deal with the consequences of breaking unwritten rules. In Michael Donoghue’s “The Problem of Being Really Good at Names,” an IRA-man has to punish a stick-up artist who stole the wrong gun from the wrong people. In Matthew R. Loney’s “From the Lookout There Are Trees,” backpackers get a glimpse of the Burma tourists don’t get to see. In Lori Pollock’s “The Royal Flush,” an earnest student learns a hard economic truth that lies beneath the academic buzzwords Sustainable Development.

If everything is political, even when it doesn’t want to be, thankfully there are some writers at work here ready to tackle that challenge.

—Niall McArdle