Reviews

Poetry Review by David Huebert

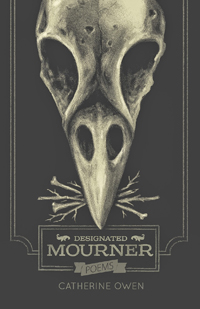

Catherine Owen, Designated Mourner (Toronto: ECW, 2014). Paperbound, 110 pp., $18.95.

Catherine Owen’s latest poetry collection, Designated Mourner, is unsettling in the

Owen organizes the poems into relatively coherent chronological order, from 2008 to 2013. The collection begins with the elegiac subject—the “you” or “him” of the poems, rarely (but crucially) called “Chris”—still alive. As the volume proceeds through this young man’s death and the speaker’s three-year period of paralyzing grief, another story emerges alongside the mourning narrative; this is the retroactive account of the deceased’s life—his ecstatic bond with the speaker, and his struggle with the addiction that led to his early death.

Chris is a lean young guitar-playing man with a love of dogs, cigarettes, metal music, and a striking passion for his beloved. Accumulating debt as he works low-paying construction jobs, the young man develops a crack habit that takes over his life and, despite his own ardent efforts and his partner’s support, he meets death shortly after his twenty-ninth birthday: “toxins wracking the nest and you, a beautiful one-time-only, / poisons captive in your brain, then from the truck’s cold cage, / your heart wrecking itself.” The young man’s “exploded heart” serves (“The Last Perfect Thing”), here and throughout the collection, as both literal and figurative cause of death. The crack he smoked and couldn’t stop smoking caused his crucial organ to cease functioning. But, like many tragic heroes of literature, he also seems in some sense simply too passionate to live a balanced, normal, boring life. In poems such as “Why I Would Try It, the Means You Died By,” this affective excess finds its outlet in the “sour cowardly exquisite risk” of the drug: “they call it blowing the devil’s dick the best climax you’ll / ever have.” But these extremes of feeling also enable the young man’s prodigious love for the speaker, a love which is “worth struggling for through all the pain of crack” (“New Year’s Day”). The romantic relationship this book investigates is enormously passionate, and at times the poems are almost unbearably intimate: “I think of you, for instance, reading / intently about the clitoris, then spending an hour / brailling me with your tongue” (“The Hardest Thing Is How Hard”). But even as the intensity of the romance flares and soars in retrospect, the reader knows that it will end in death and the poet’s abysmal loneliness. Happiness, here, is never unequivocal; rather, in the world of these poems there is only “terrible pleasures” and the “terror of happiness” which always provokes its opposite (“Erotics of the Dead”; “migration: things taken, what of this counts”).

The poet’s relentless exploration of trauma, evident throughout the collection in recurring tropes such as corpses, autopsies, cremation, and ash, also emerges within the formal structure of the poems. Owen writes sonnets, ghazals, madrigals, and villanelles, but they are almost never technically standard or formally consistent. Of the four sonnets I noticed, no two have the same rhyme scheme or stanza structure. Though she uses the scaffolding of established forms, Owen refuses to close her poems off with technical autonomy. Instead, she leaves them open, allowing a haunting presence to move into the gaps. This also emerges in her spectral free verse. Take, for example, “Poem Without the Word Heart”:

I’m speaking about the and then

once you know it explodes well

you imagine what the (drawn from the body)

resembles and you remember lying on his chest

and hearing the beating alive alive alive

and you begging him not to do that again to the

because he knew now didn’t he that it is not

sweet & clichéd the that is the of everything

Given the heart’s enormous importance to the book as a whole, its absence here becomes all the more potent. By omitting the word “heart” and leaving ghastly white pauses in its stead, Owen highlights the “hushed explosion” that haunts us throughout the collection.

—David Huebert