Reviews

Poetry Reviews by Michael Greenstein

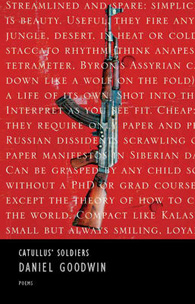

Daniel Goodwin, Catullus’s Soldiers (Toronto: Cormorant, 2015). Paperbound, 70 pp., $18.

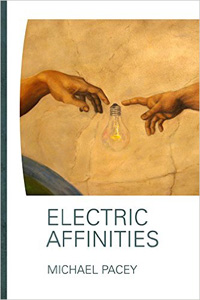

Michael Pacey, Electric Affinities (Winnipeg: Signature, 2015). 96 pp., $14.95.

The cover of Michael Pacey’s Electric Affinities portrays two hands reaching to touch a lightbulb against the backdrop of the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling. “Light Bulb” examines some of the implications of this cover. The poem opens bluntly, and connects mind and matter, lightbulb and abstraction: “Icon of pure idea.” In his sensory grammar, Pacey emphasizes nouns and sounds, and often downplays verbs. We are further immersed in the phenomenology of this everyday object: “Screwed into a sphere of permanence / skin-thin, fragile as eggshell, yet suffused / with even light.” By inspecting the imagery surrounding an ordinary lightbulb, the poet imparts permanence to evanescence: “a Platonic corona identical / to the thinking mind’s delicate glow.” A penumbra connects the bulb to its immediate surroundings and to the broader implications of other minds. The word “identical” establishes identity for the object and relates it to its metaphoric potential. The poet illuminates the experience of what we take for granted. His rhythms complement the visual nature of the poem’s stanzas. Sentences begin emphatically and invitingly: “Say,” “Naked,” “Screw a few in just for fun,” and “Installation’s easy.” “Light Bulb (II)” opens with “Quick tweaks / of the wrist— / in series— .” “Light Bulb (III)” further highlights the writing process: “A string of metaphors / —in series—.” Pacey’s similitudes, two-handed dichotomies, and hum and drum of conundrums shine and flash in each poem: “Like and unlike rubbing together, / the kindred and the incongruous.”

The cover of Michael Pacey’s Electric Affinities portrays two hands reaching to touch a lightbulb against the backdrop of the Sistine Chapel’s ceiling. “Light Bulb” examines some of the implications of this cover. The poem opens bluntly, and connects mind and matter, lightbulb and abstraction: “Icon of pure idea.” In his sensory grammar, Pacey emphasizes nouns and sounds, and often downplays verbs. We are further immersed in the phenomenology of this everyday object: “Screwed into a sphere of permanence / skin-thin, fragile as eggshell, yet suffused / with even light.” By inspecting the imagery surrounding an ordinary lightbulb, the poet imparts permanence to evanescence: “a Platonic corona identical / to the thinking mind’s delicate glow.” A penumbra connects the bulb to its immediate surroundings and to the broader implications of other minds. The word “identical” establishes identity for the object and relates it to its metaphoric potential. The poet illuminates the experience of what we take for granted. His rhythms complement the visual nature of the poem’s stanzas. Sentences begin emphatically and invitingly: “Say,” “Naked,” “Screw a few in just for fun,” and “Installation’s easy.” “Light Bulb (II)” opens with “Quick tweaks / of the wrist— / in series— .” “Light Bulb (III)” further highlights the writing process: “A string of metaphors / —in series—.” Pacey’s similitudes, two-handed dichotomies, and hum and drum of conundrums shine and flash in each poem: “Like and unlike rubbing together, / the kindred and the incongruous.”

Aside from domestic objects, Pacey’s poetics of space includes small details from nature, individual letters of the alphabet, and other writers such as Shakespeare and Tennyson. In “Nests” he juxtaposes “the oriole’s familiar metaphor — / the domestic scene hanging by a thread,” and concludes with witty bricolage: “gluey strings of words moved around, / the template inside; held in place, stuck with sweat, / with spit, to the sheer edge of a page.”

Daniel Goodwin’s Catullus’s Soldiers directs its gaze outward toward social, political, and historical spheres. The cover of this collection displays an AK-47, the weapon designed by the poet Mikhail Kalashnikov. Goodwin pays tribute to him in “AK-47”: “The best poems work like an AK-47, / Streamlined and spare.” The poem progresses through a series of similes, equating poetry and firearm: “Compact like Kalashnikov, / small but always smiling.” Staccato and simile continue: “Rough-hewn gun with ancient rhythms / … the intricate art like Robert Frost’s.” The poet concludes: “Why am I not surprised Kalashnikov / wrote poetry with his other hand?” Just as Kalashnikov is both poet and warrior, so too is Catullus, whose “other hand” appears in “Catullus in a Martial Moment”: “They march to a cadence of my choosing, / across the page like a wave of soldier ants.”

Daniel Goodwin’s Catullus’s Soldiers directs its gaze outward toward social, political, and historical spheres. The cover of this collection displays an AK-47, the weapon designed by the poet Mikhail Kalashnikov. Goodwin pays tribute to him in “AK-47”: “The best poems work like an AK-47, / Streamlined and spare.” The poem progresses through a series of similes, equating poetry and firearm: “Compact like Kalashnikov, / small but always smiling.” Staccato and simile continue: “Rough-hewn gun with ancient rhythms / … the intricate art like Robert Frost’s.” The poet concludes: “Why am I not surprised Kalashnikov / wrote poetry with his other hand?” Just as Kalashnikov is both poet and warrior, so too is Catullus, whose “other hand” appears in “Catullus in a Martial Moment”: “They march to a cadence of my choosing, / across the page like a wave of soldier ants.”

Goodwin’s historical imagination includes personal family history. “Heritage” chronicles his dual identity: “You wear the burden lightly, my son / of those who went before you: / Dutch and Jew.” The oxymoronic light burden, displaced syntax, rhyme, and double ancestry lead to “two small nations / scattered or squeezed between empires, / the domestic sphere the only safe harbour.” The poem ends with a simile: “like a rolled-up Torah or canal boat,” that underscores Semitic and Dutch roots within the “narrow straits of civilization.”

Within Goodwin’s domestic sphere, one encounters “Domestic Epic” and “Domestic Arguments.” While the poet is “upstairs with words,” he describes his family’s routine: his son plays with the confidence of an “Old Testament god,” and his daughter speaks to her “Bubbe,” mixing myths and “Homeric epics.” Navigating between Hebraic and Hellenic poles, Goodwin portrays a well-rounded, three-dimensional tapestry. The sonnet, “Domestic Arguments,” presents a family feud: “They blur the lines: who’s right, whose wrong, / the same old dance, the same old song.” His dancing dialectic ends with the everlasting moment’s monument: “And we wonder what happened to the future. / But something of before endures.”

A number of poems are devoted to the poet’s father, William Goodwin, 1916 – 1999. “My Father’s Books” lists a library of Penguin Classics and first editions of Montreal relatives and family friends, including Irving Layton, whose influence is unmistakeable in “The Butterfly” and “The Bull.” Allusive yet accessible, Goodwin wears his learning lightly and with considerable wit. His similes and soldiers move in many directions in “Sixteen Ways of Looking at a Poet.”

Michael Pacey’s father, Desmond, who was also a writer, figures in his son’s “Escalator Down,” another domestic epic. For all their differences, Goodwin and Pacey share affinities in their affiliations. Pacey traces the letter “Y” as an old tree, a fork in the road, a river dividing and converging. “Y is always the meeting, / and Y / the parting ways.” Pacey’s phenomenological icons and Goodwin’s soldier-poets converge on the page in alternating currents of surprise and satisfaction.

—Michael Greenstein