Reviews

Poetry Reviews by Danielle Janess

Raoul Fernandes, Transmitter and Receiver (Gibsons: Nightwood, 2015). Paperbound, 80 pp., $18.95.

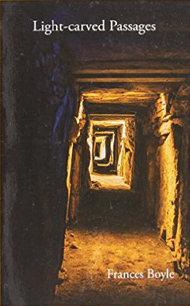

Frances Boyle, Light-carved Passages (Ottawa: Buschek, 2014). Paperbound, 84 pp., $17.95.

If reading the poems in Raoul Fernandes’ debut collection Transmitter and Receiver leaves you feeling as if the speaker could be your friend, as if “in a neighborhood in East Vancouver on a rainy evening near the beginning of summer” you could share “a couple of cans of ipa,” it could be the effect of the humility that characterizes this book. This humility, an unpretentious regard for the inner lives of objects and persons, is communicated by the speaker in, at times, an almost childlike tone for its sense of wonder and associative leaps. One might imagine the mind of these poems as a prescient grade-schooler who, taking the hand of the reader, leads her on his own familiar walk, introducing every being and non-being along the way.

If reading the poems in Raoul Fernandes’ debut collection Transmitter and Receiver leaves you feeling as if the speaker could be your friend, as if “in a neighborhood in East Vancouver on a rainy evening near the beginning of summer” you could share “a couple of cans of ipa,” it could be the effect of the humility that characterizes this book. This humility, an unpretentious regard for the inner lives of objects and persons, is communicated by the speaker in, at times, an almost childlike tone for its sense of wonder and associative leaps. One might imagine the mind of these poems as a prescient grade-schooler who, taking the hand of the reader, leads her on his own familiar walk, introducing every being and non-being along the way.

For Fernandes, the poem is an opportunity for connection, with self and dreams, with family and stranger, but also with the electronic file attachment, and the vacant retail space. In “Automatic Teller,” a sentient atm “wonders why / the woman looks so sad / when it prints out / pale numbers / on a small piece of paper.” In “Mixtape” a teenage boy “collects his friends’ broken Walkmans / and builds a flying machine out of them.” “Attachments” is a list of .jpg file attachments that catalogue the speaker’s nostalgia with titles like, “thiskidnobodyknowswearingthepuffiestjacket everandweallcallhimlittlelionwhichheseemstolike.jpg.” Because an electronic photograph and memory itself are immaterial, such witness to the unseen emotional life of technology and of the speaker works to soften possible egoism in the poem’s title pun. In other hands such tenderness could be rendered soppy, but this transmitter is not dull, although the wit here seeks to illuminate and comfort, rather than to jab or brag.

The poems in the first section are a dialogue with media and technology, while section two revisits adolescence, and the final section negotiates the sometimes-wobbly transition to adulthood, marked by work poems that talk of stress and a chronic “knot in the shoulder,” and poems dedicated to wife and child. In the poems’ sometimes strangeness, “I pour myself a cup of numbers in the kitchen,” and free-thinking associations, Fernandes nods to the thought-buoyancy of contemporary American poets such as David Berman with lines like “walking through the sensor gate at the public library / after a heavy reading, you fear the alarm / will go off from what is held in your mind.” Occasionally I wanted more air, less certainty, at the conclusion of poems like “Thirteen Summers For Timothy Treadwell” and “Affordable Travel Through Time,” where the omniscience of the last lines can feel too sewn-up. But, overall, the poems lean open; they question rather than proclaim. Less-successful attempts at transmission occur beside instances of clear, abiding hope, as in “Car Game,” when a man’s loose shirt becomes “a white flag” even as he “stands on / the railing of a bridge […]/ studying the waves.” Rather than join the ranks of impatient rush hour drivers who wait for the drama to pass, Fernandes urges us to attention and empathy. The effect is of transcendence; the poet acknowledges despair but will not go numb. “You have to let go of something,” he tells us, “to reach what you are trying to reach. […] You must let go and fall / in one direction or another.”

Ottawa poet Frances Boyle’s first book, Light-carved Passages, also conveys a reverence for dual natures. The book’s cover shows a tunnel with doorway arches illuminated by a sepia-golden glow. Walls obscured, openings visible, this is where we are headed. Early in the book, “Sepia” likens memory to a rusk at which the poet scrabbles, while reflections are “sepia / old photographs letters aged in tea.” In Italian art, chiaroscuro was an important technique in the development of realism. Boyle, too, brackets shadow with highlight in order to contour the images, emotions, and characters brought to life in these poems. Consider this excerpt from the opening poem, “Inarticulate emotion,” where the abrupt turn from exuberant to bitter illustrates the pair’s opposite states, the final caesura of a marriage:

Ottawa poet Frances Boyle’s first book, Light-carved Passages, also conveys a reverence for dual natures. The book’s cover shows a tunnel with doorway arches illuminated by a sepia-golden glow. Walls obscured, openings visible, this is where we are headed. Early in the book, “Sepia” likens memory to a rusk at which the poet scrabbles, while reflections are “sepia / old photographs letters aged in tea.” In Italian art, chiaroscuro was an important technique in the development of realism. Boyle, too, brackets shadow with highlight in order to contour the images, emotions, and characters brought to life in these poems. Consider this excerpt from the opening poem, “Inarticulate emotion,” where the abrupt turn from exuberant to bitter illustrates the pair’s opposite states, the final caesura of a marriage:

A husband on a dock in Colombo

mimes farewell, farewell to the ship […]

throws his whole being into the gesture,

waves himself into water, blue against the sky […].

The wife turns like the harbour tide, heads

back to the hotel, disavows the dumbshow,

walks away from fourteen years

of hoarded grudges. She denies affiliation.

Such domestic tension recurs throughout the book, as daughters and mothers, husbands and wives alternately struggle with and soothe one another. Rich in imagery, attentive to language and music, the poems have a strong narrative style, often so intensely personal that the reader winces alongside the speaker’s strain.

Loyal to the bonds between women, in “Sort of an Elegy, ii. And the room breathed,” the speaker says she, “believe[s] a woman I haven’t seen for nineteen years / is still my friend.” Dedications to poets such as Sylvia Plath, Gwendolyn MacEwen, and Brecken Hancock indicate Boyle’s apprenticeship to poems that plumb emotion, secrets, and family history. As a whole the collection speaks to lived experience. “I resist the idea of loss,” the speaker says in “And the room breathed.” “My life has been but one thread, spooling out / with other coloured threads, not in tapestry but in knots and tangles.”

—Danielle Janess