Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Carleigh Baker

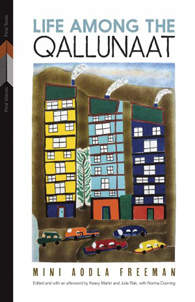

Mini Aodla Freeman, Life Among the Qallunaat (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 2015). Paperbound, 278 pp., $24.95.

Mini Aodla Freeman’s memoir, Life Among the Qallunaat, is the third book from the University of Manitoba Press First Voices, First Texts series, which publishes “under-appreciated” texts by indigenous writers. But this isn’t just a reissue; the press has gone one step further by revisiting Freeman’s original typescript and working directly with the author to ensure her writing style and voice are honoured. Life Among the Qallunaat stands out among neglected indigenous texts, not only for its merit, but for the treatment the book received when it was first published in 1978.

Mini Aodla Freeman’s memoir, Life Among the Qallunaat, is the third book from the University of Manitoba Press First Voices, First Texts series, which publishes “under-appreciated” texts by indigenous writers. But this isn’t just a reissue; the press has gone one step further by revisiting Freeman’s original typescript and working directly with the author to ensure her writing style and voice are honoured. Life Among the Qallunaat stands out among neglected indigenous texts, not only for its merit, but for the treatment the book received when it was first published in 1978.

Here’s the story behind the story. After its publication, over half of the print run of Life Among the Qallunaat—approximately 4200 copies—was seized by the Department of Indian and Northern Affairs. The books sat in the department’s basement for about eight months, awaiting official approval, presumably for content relating to residential schools and Inuit relocation programs. Positive reviews in the Globe and Mail and Toronto Star, and consideration for the 1978 Governor General’s medal shortlist didn’t have much of an effect on sales, because there were no books to sell. The book was finally read and approved for distribution by someone at the Department of Indian Affairs, but still only made it into the hands of a relatively small readership. Life Among the Qallunat was never re-printed, nor was a paperback edition published. This triumph of indigenous literature, as humorous and disarming as it is harrowing, is finally back in circulation.

The brilliance ofthis book lies in Freeman’s perceptive and insightful writing, but its effectiveness lies in its accessibility. Told in a series of short, digestible anecdotes along a fairly linear timeline, readers who are unfamiliar with Inuit culture will find it easy to peruse. Freeman possesses a life perspective and experience that non-indigenous readers may find utterly foreign. With humour and deceptively simple language, she opens that world up to us.

Freeman was born in 1936 on Nunaaluk (Cape Hope) Island in James Bay. I’ll give you a second to Google that. Okay. Every day without fail, Freeman and her brother were under grandmother’s orders to “go out, look at the world,” to “greet and adore the things that are disposed to us.” This pragmatic acceptance of the environment isn’t presented with any pretension of northern mysticism. Quite the opposite. “Having to do this every day in our childhood became a joke to me and my brother. We would burst out laughing. What were we looking for?” The reportage of this simple daily routine is an effective call to action for readers, a reminder that in order to properly appreciate her story, we need to see the world through Freeman’s eyes.

The first few chapters of Life Among the Qallunaat tell the story of a young woman in an entirely foreign environment—using elevators, telephones, stoplights, and even electricity itself, which Freeman had been taught “came from thunder and lightning.” The mundane world and social norms are examined and analyzed with humour and honesty. We are being lightly teased by Freeman, in a narrative voice that subtly mimics the “voice of God” narration of early colonial explorers when documenting Inuit culture.

While her grappling with the trappings of 1970’s modern life provides some amusement, Freeman’s life philosophy is what really makes her story unique. “I am Inuk—I do not shape my future for my own gain. I let others shape it for me and learn to take whatever comes, good or bad.” This seemingly passive attitude might not make Freeman very popular with some modern feminists, but in the context of the memoir and Freeman’s wildly interesting life journey, it makes for fascinating reading. Her superb adaptability is the story here. She may not see her role as a shaper of the future, but her ability to excel in any situation she encounters is extraordinary, especially, as she gracefully points out, within the context of a society that considered her a savage—barely a human being.

One evening, I arrived at the teacher’s house and as usual took off my coat and sat myself at the piano. […] She never used my name. This evening, she did not get on with the lesson, but spoke. “You Natives are so talented, you Natives should take advantage of your free education, you Natives should aim for higher things.” You Natives should this and that. I just sat there taking it all in. She had never spoken so much to me before.

Although raised to be polite and accommodating, Freeman is keenly aware of her own character arc, and how her response to this racist behaviour changed as she matured. Readers of all backgrounds will take great satisfaction her achievements.

From out of the basement and into the hands of readers, Life Among the Qallunaat is funny, engaging, and honest. Indigenous lit is hot right now, but a rapidly expanding market can overlook diversity. Mini Aodla Freeman’s writing will quietly blow your mind, and I’m thankful to University of Manitoba press for their efforts with the First Voices, First Texts series.

—Carleigh Baker