Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Candace Fertile

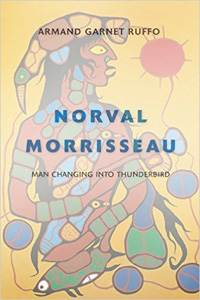

Armand Garnet Ruffo, Norval Morrisseau: Man Changing into Thunderbird (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 2014). Hardcover, 312 pages, $32.95.

In the Introduction to Norval Morrisseau: Man Changing into Thunderbird, Armand Garnet Ruffo lays the groundwork for the genre bending that follows. He makes it clear that he is not writing a standard biography. Instead he wanted to “tell a story,” and to honour his own culture (and that of Morrisseau) by using “the traditional form of acquiring knowledge that is central to Ojibway culture and to Native cultures in general.” So what follows is a form sometimes called “creative biography.” Ruffo includes biographical information, poems, pictures, and many imagined scenes of Morrisseau’s life. The book is indeed a complicated amalgam of form and content.

In the Introduction to Norval Morrisseau: Man Changing into Thunderbird, Armand Garnet Ruffo lays the groundwork for the genre bending that follows. He makes it clear that he is not writing a standard biography. Instead he wanted to “tell a story,” and to honour his own culture (and that of Morrisseau) by using “the traditional form of acquiring knowledge that is central to Ojibway culture and to Native cultures in general.” So what follows is a form sometimes called “creative biography.” Ruffo includes biographical information, poems, pictures, and many imagined scenes of Morrisseau’s life. The book is indeed a complicated amalgam of form and content.

Overall, in an extremely loose chronology, Ruffo retells Morrisseau’s life as he sees it: it’s critical that readers understand the book is a collection of Ruffo’s impressions about his subject. And the complexity of Morrisseau comes through forcefully. Born in 1932, Morrisseau is likely the most famous of First Nations artists, in part because of his stupendous output and his outrageous behaviour. He could be wonderfully kind but also appalling. He was enormously gifted and dedicated. He was a terrible husband and father, abandoning his wife and seven children to a life of poverty while he painted and caroused. He had serious problems with alcohol addiction, was in and out of jail, and lived on the streets for a while. Often surrounded by people who were mostly interested in how much money they could make from his paintings, he used people as well. And to this day a controversy exists about possibly fake Morrisseau paintings. As Ruffo notes, “whatever the truth, the current storm of accusations and litigation shows no sign of dispersing. No sign of light.”

Ruffo doesn’t hold back on the bad behaviour but there’s some suggestion that gifted artists should be allowed some latitude. Morrisseau was a creature of contradictions, and Ruffo’s assessment of Morrisseau as embodying the effects of the attempted erasure of Ojibway culture (among all First Nations cultures) is compelling. Given the tragedy of forced assimilation and constant denigration, First Nations people have many wounds, wounds that are both physical and emotional. And these wounds are not going away any time soon. How could they?

So it is against massive obstacles that Morrisseau prevailed as the artistic genius he so obviously is. Abused by priests in residential school, Morrisseau had a difficult time resolving his own sexuality and uses his painting as one way to come to grips with his internal reality. But the paintings are more than that. Ruffo is careful to explain how Morrisseau’s work was based on his grandfather’s stories: the stories of the Ojibway.

At the heart of the book is the question of identity, both on an individual and a cultural level. Once the culture is attacked, the individual also suffers, as identity is connected to one’s community. That Morrisseau prevailed as an artist is a testament to his strength and his belief in the value of the Ojibway culture.

While reading, I couldn’t help wondering what Ruffo means by “knowledge.” Story-telling is an essential way to communicate, to teach, but story-creating may be another matter. Over and over, I found myself asking, “How does Ruffo know this?” He has not given specific sources for material, and he frequently writes about things he cannot possibly know. For example, Ruffo imagines the response of a woman looking at Artist in Union with Mother Earth, which depicts sex. Ruffo writes: “Having trained herself in creative visualization, she can feel the sexual energy travel through her body.” Or Ruffo imagines Morrisseau at the age of six waiting for his grandfather: “And among these objects [in the room], his grandfather begins to take shape, his faint silhouette moving across the room. And then, with eyes turned and fixed to the east-facing window, Norval watches how all the colours of day become compressed into a single moment.” Of course, Ruffo has warned us that his goal is not to write a biography, but I was deeply distracted by the tangle of fiction and nonfiction.

In “The Garden Party,” one of the most entertaining and exasperating stories, Ruffo uses his customary fragment-laden prose but shifts the point of view to the second-person. He describes a lavish tea party that Morrisseau held in a tiny place 750 miles north of Toronto. Morrisseau chartered a plane for his invitees. Ruffo writes, “Beside you are the twenty guests who have also made the trip and, because of the flight, whom you feel you have known forever.” It’s as if Ruffo is a guest, but as the party happened in the 70s and Ruffo never met Morrisseau until after the National Gallery of Canada asked him, in 2005, to write a piece for the catalogue to accompany the Norval Morrisseau, Shaman and Artist retrospective. So whose point of view is it? Some of the people listed in the Acknowledgments were at the party, but there’s no way of knowing the specifics. Or did it even happen?

Ultimately, I closed the book with an overwhelming sense of frustration. Understanding what I was reading was like trying to catch a firefly in the daytime. Where is the light? What am I supposed to believe? In his quest to honour a particular ancestry and tradition (a worthy endeavour), Ruffo may have ignored another tradition—that of the pact of trust between writer and reader.

—Candace Fertile