Reviews

Fiction Review by Shannon Webb-Campbell

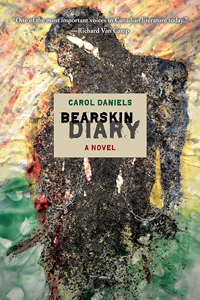

Carol Daniels, Bearskin Diary (Madeira Park: Nightwood, 2015). Paperbound, 256 pp., $21.95.

Fact and fiction are shapeshifters depending on the teller. Renowned author, poet, and journalist Carol Daniels explores the nature of truth in her debut novel, Bearskin Diary. Daniels, who became Canada's first Aboriginal woman to anchor a national newscast when she joined CBC in 1989, spent her career telling other people's stories. When Daniels delved into her own creativity, and her own narratives and experience, she found deep roots of inspiration.

Fact and fiction are shapeshifters depending on the teller. Renowned author, poet, and journalist Carol Daniels explores the nature of truth in her debut novel, Bearskin Diary. Daniels, who became Canada's first Aboriginal woman to anchor a national newscast when she joined CBC in 1989, spent her career telling other people's stories. When Daniels delved into her own creativity, and her own narratives and experience, she found deep roots of inspiration.

Bearskin Diary follows protagonist Sandy, a reporter, who was one of twenty thousand Aboriginal children taken from their mothers by the federal government between the 1960s and 1980s. As a child in her small town, Sandy was the only Cree for miles—not that anyone knew what it meant to be Cree. Adopted into a Ukrainian family, Sandy was the only brown-skinned child amidst a sea of white grain on the flat prairie landscape. She even tried to scrub off her dark skin in the hope of fitting in. Like thousands of Indigenous people, Sandy was part of the "Sixties Scoop," and as a result lost her First Nations community, and customs. Throughout Bearskin Diary, Sandy struggles with her identity, culture, and sense of self. Themes of self-esteem, shame, and isolation are constant; including struggles with sex, alcohol, love, and belonging, though Daniels also sprinkles the text with offerings of intuition, healing, and insight.

While Sandy navigates internal and external discriminations from schoolmates, co-workers, strangers, and even herself, she eventually starts to connect with her culture and history through telling stories as a pioneering Indigenous television reporter. However, the position doesn't come without challenges of being ostracized and emotionally abused. "Sandy's recollection of those first days on the job make her realize that rarely does she feel fresh—more like some cheap token. A cigar-store Indian, here for show but expected to keep silent. A hard thing to admit. The day-to-day shunning has continued with ugly undertones suggesting she doesn't belong in this job, this industry." Sandy's knack as a storyteller and truth-seeker get her into some tricky situations, and the crux of the novel hinges on a close encounter with becoming a statistic—another woman on the list of missing and murdered Indigenous women.

Daniels highlights the larger issues surrounding First Nations people in Canada in portraying the connection between Sandy and her lover, Blue, a Métis man who didn't grow up on the rez, and who is in deep denial of his own heritage. Part of what captivates Blue about Sandy is what ultimately pushes him away. "It startles Blue to admit that he no longer sees Sandy as the sweet inquisitive girl who happens to be brown. Ever since moving here, she's sounding more like those Aboriginal women the police department hires to do Aboriginal awareness training. He thinks about one of those training sessions held last month."

One of the insights from Aboriginal awareness training strikes Blue in particular—how some Native men refer to Native women as buckskins, as if ashamed of their own culture. They only date white women, and say Aboriginal women are only meant to try on, and discard when they are finished. His last partner was a white woman, and he can't quite shake her. Blue is both bystander and antagonist, a complex character in Bearskin Diary. The connection between him and Sandy highlights issues of colonialism and generational trauma. Their relationship is cloaked in shame. "It frustrates him that these nagging thoughts emerge. He forces himself to ask, deep down, whether he is ashamed of Sandy, whether he is ashamed of himself. Blue rubs his forehead as though doing so will wipe away the bad thoughts."

Daniels also highlights several issues facing First Nations women; including marginalization and silence, and, as the plot twists, she addresses Canada's national inquiry into the missing and murdered Aboriginal women. As a First Nations Mi'kmaq reader, writer, and journalist, I found elements of myself in Daniels' pages—drowning in Merlot, being in the arms of the wrong lovers, and writing other people's stories in attempt to find my own voice. Much like Sandy, I had anxiety going to my first powwow, and questions around the exploration of my Indigenous roots. Eventually, visions came, along with moments of teachings, offerings, and medicines. Eagles even started to soar overhead. As Daniels writes: "Today, a lone bald eagle flies directly over her vehicle as she drives. It's going to be a good day. She smiles to herself, recalling an Aboriginal teaching that Joe mentioned. 'The bald eagle watches over the spirit of Aboriginal peoples because it flies higher than any other bird. It is able to communicate between the Earth and the Spirit world.'"

It's Daniels' honesty and concise diction that make Bearskin Diary a powerful, and captivating read. Her voice is authentic, melodic, and artfully captures an integral perspective in Canadian letters. Daniels' own artwork is featured on the cover, originally a five-foot painting made with dirt and acrylic based on a story by an Aboriginal Elder who ran and hid as a child in the pre-1960s every time he heard the Indian Agent's car driving close to his house. The image embodies fear, pain, and skulls in the body of the agent, and draws parallels between stolen children in the residential school system, and the Sixties Scoop.

—Shannon Webb-Campbell