Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Rachel George

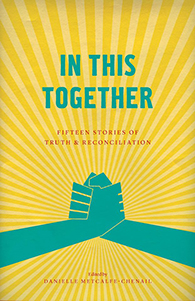

Danielle Metcalfe-Chenail, ed., In This Together: Fifteen Stories of Truth & Reconciliation (Victoria: Brindle & Glass, 2016). Paperbound, 224 pp., $19.95.

The discourse of reconciliation has dominated the socio-political climate in Canada with increasing intensity since the June 2015 release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s summary report and ninety-four calls to action. For many across the country, what “reconciliation” means in the daily lives of Indigenous peoples has yet to be truly grappled with. Those of us who are Indigenous understand that for an improvement in relations to occur, a necessary, multi-faceted approach to decolonization must pervade the consciousness of all those who call themselves citizens of Canada. In an attempt to tackle the question of reconciliation, In This Together: Fifteen Stories of Truth & Reconciliation compiles narratives and personal reflections from journalists, writers, academics, visual artists, filmmakers, city planners, and lawyers.

The discourse of reconciliation has dominated the socio-political climate in Canada with increasing intensity since the June 2015 release of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada’s summary report and ninety-four calls to action. For many across the country, what “reconciliation” means in the daily lives of Indigenous peoples has yet to be truly grappled with. Those of us who are Indigenous understand that for an improvement in relations to occur, a necessary, multi-faceted approach to decolonization must pervade the consciousness of all those who call themselves citizens of Canada. In an attempt to tackle the question of reconciliation, In This Together: Fifteen Stories of Truth & Reconciliation compiles narratives and personal reflections from journalists, writers, academics, visual artists, filmmakers, city planners, and lawyers.

In perhaps a deliberate attempt to allow the selected pieces to speak to their own understandings of “reconciliation,” the compilation is markedly devoid of critical perspectives of what is meant by the term. At its root, reconciliationdenotes a restoration of “friendly relations,” or a process of making two different ideas/facts compatible. Yet, any honest examination of the history of Canada would illustrate that “friendly relations” were few and far between. Current concepts of Canada as a benevolent, human-rights-adhering, peace-making nation are utterly incompatible with the true history of this country and its relationship with, and treatment of Indigenous peoples. At the heart of this collection is each contributor’s deep individual struggle to reconcile previous concepts of national identity with new understandings of national history while reflecting on the moment they each came to know about residential schools or about racism. The inherent struggle in reconciling opposing concepts of Canada is explicit through many of the pieces, but it emerges most prominently in a statement by Rhonda Kronyk: “Yet, even though ‘colonialism’ and ‘genocide’ are the correct words to use in Canada’s modern context, I wonder if they do more harm than good.”

Positionality becomes critical to understanding the intent and trajectory of this collection. Largely written by non-Indigenous writers, it seeks to welcome other non-Indigenous Canadians to the challenging conversation of reconciliation. Built on each author’s “ah-ha” moments as it pertains to Canada’s colonial past, In This Together endeavours to present how to move forward in the spirit of reconciliation and anti-racism while attempting to understand: “what is real reconciliation?” However, any confrontation of injustice among its non-Indigenous contributors centres primarily on residential-school policy and experience. Further, while the editor, Danielle Metcalfe-Chenail, provides no specific definition as to what “reconciliation” means, the particular understanding that is advanced by most contributors ultimately silences the breadth of Indigenous peoples’ colonial experience. This is how any serious framing of decolonization is continually marginalized, as well as any meaningful understanding of our rights and responsibilities as Indigenous peoples, particularly when it comes to our relationship with our lands, and self-determination. The understanding of reconciliation as put forward in this collection does not to speak to the deeply difficult conversations that are necessary to envision new relationships between Indigenous peoples and all Canadians.

Each individual reflection on racism, ranging from discussions of learning about residential schools, to foster care, to attempting to have more Indigenous voices heard in city planning, strives to suggest a step forward hinged on the principle of “just begin.” Many of these steps forward can be distilled simply to “more historical education,” “recognizing wrongs,” and “building individual relationships.” Yet, for Indigenous peoples who continue to battle against colonial policies that infringe on our territories, on our bodies, and on our daily lives, the discussion of reconciliation, as framed here, neglects to make a substantial difference. While these tasks are important, they are but mere half-measures in creating a new relationship. The silence on self-determination, and on the importance of our lands, and our responsibilities to our lands within the reconciliation discourse and, ultimately, within this collection, only furthers the colonial agenda. These “acts of reconciliation” continue to advance the notion of truth as justice, but do nothing to genuinely challenge colonial policies or the inherent racism that pervades Canadian consciousness.

While there are selected articles within In This Together that touch on aspects that are necessary for a new relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, such as Métis-Cree contributor Kamala Todd’s reflection on the power of making space for marginalized voices, the collection as a whole does not challenge the status quo. It merely scratches the surface of what is necessary in this country. Reconciliation, as presented here, does not disrupt current colonial policies, nor can it spark the systemic change that is necessary. Naming and challenging colonialism and genocide does not potentially “do more harm than good,” as suggested by Rhonda Kronyk; instead they seek to destabilize a system that desperately needs to be rebuilt. While this anthology emphasizes the prominence of education in improving relations, the silence on such core tenets as self-determination sets to found a relationship based on the denial of rights. Concrete redress includes land, and real justice means respecting self-determination. Anything less than this is a miscarriage of justice, a continuation of colonial practices, and does not represent “real reconciliation.” Although In This Together strives to contemplate “how we can move forward in a spirit of reconciliation and anti-racism,” the discussion must go much deeper than it presents. The silence on what’s critical fails to truly engage readers in the difficult conversations essential for a new relationship to occur.

—Rachel George