Reviews

Fiction Review by Nora Decter

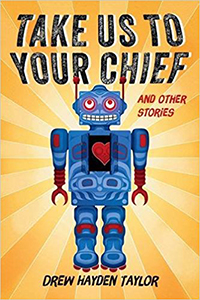

Drew Hayden Taylor, Take Us to Your Chief and Other Stories (Madeira Park: Douglas & McIntyre, 2016). Paperbound, 150 pp., $18.95.

Drew Hayden Taylor has been experimenting with literary hybrids for a long time. “Perhaps it goes all the way back to my dna,” he writes in the foreword to Take Us to Your Chief, “I’m half Ojibway and half…not.” Throughout his twenty-five-year career, Taylor has published work in nearly every form imaginable (novels, graphic novels, essays, and many, many plays) and every genre and sub-genre out there, from magic realism to comedy to vampires. Despite this incredible literary range, the intention behind Taylor’s experimentation remains the same: to expand the definition of First Nations literature. As he explains in the foreword, “a lot of Indigenous novels and plays tend to walk a narrow path specifically restricted to stories of bygone days. Or angry/dysfunction aspects of contemporary First Nations life….All worthwhile and necessary reflections of Aboriginal life for sure. But I wonder why it can’t be more?” Answering that question has sent Taylor’s writing journey across genres, and now galaxies, as his new collection of short stories smashes together the seemingly disparate worlds of First Nations literature and science fiction.

Drew Hayden Taylor has been experimenting with literary hybrids for a long time. “Perhaps it goes all the way back to my dna,” he writes in the foreword to Take Us to Your Chief, “I’m half Ojibway and half…not.” Throughout his twenty-five-year career, Taylor has published work in nearly every form imaginable (novels, graphic novels, essays, and many, many plays) and every genre and sub-genre out there, from magic realism to comedy to vampires. Despite this incredible literary range, the intention behind Taylor’s experimentation remains the same: to expand the definition of First Nations literature. As he explains in the foreword, “a lot of Indigenous novels and plays tend to walk a narrow path specifically restricted to stories of bygone days. Or angry/dysfunction aspects of contemporary First Nations life….All worthwhile and necessary reflections of Aboriginal life for sure. But I wonder why it can’t be more?” Answering that question has sent Taylor’s writing journey across genres, and now galaxies, as his new collection of short stories smashes together the seemingly disparate worlds of First Nations literature and science fiction.

So what exactly does this literary mash-up look like? At first, the opening story, “A Culturally Inappropriate Armageddon,” seems to hew closely to the clichés of each genre. Set at C-RES, a radio station on an unnamed reservation, the plot will be familiar to anyone who has seen Independence Day (a ufo approaches Earth and humankind scrambles to prepare for its first contact with extraterrestrials). The characters and even the writing itself lean on cliché, and structurally the story can feel disjointed because of the years-long breaks in between sections. These are calculated moves on Taylor’s part, though; as he wisely keeps the story humming along before our curiosity about how these genres are going to cohabit can fade. That is the magic trick here, not the writing or the plot, but the way Taylor deftly exploits the assumptions with which readers approach these stories. We see this when a character compares how journalists are referring to the approaching UFO to how the history books refer to Europeans arriving in North America. “Did you hear what they’re calling it? ‘Contact.’ Does that sound familiar to either of you? Man, I bet both sides already have people drawing up treaties.”

Expectations are subverted again when we jump ahead to a post-“contact” world. The aliens have razed the surface of the Earth and reduced the population of North America to 100,000 people, all of whom are either enslaved or in hiding. The c-res staff are among the latter, hiding under a bridge, roasting a raccoon for dinner. There is a satisfying irony to this scene (rather than being upset, the group are matter of fact about the invasion, as if it’s not their first genocide) that’s made more satisfying when we learn why the aliens invaded. Turns out, it was c-res’ fault, and by trying to preserve their language they actually brought about the apocalypse. It’s a big leap, but this is a story that requires the reader to make many such leaps in logic and in time, and they pay off in the end. Taylor is an expert at using pacing to control tone, and knows that staying in these scenes any longer would make them less funny, more grave.

Having established this playfully subversive tone, the rest of the collection is a romp through terrain that—once recognizable—has been made over by Taylor’s Frankenstein-esque treatment of genre. Science fiction, even when it is playing out the end of the world, is still intended to entertain, and Taylor leads with that, letting the seriousness of his themes arise unexpectedly.

The formula of “familiar plotline, unfamiliar perspective” repeats throughout. “I Am…Am I” follows a robotics ethicist as she creates a form of artificial intelligence. Unexpectedly, the AI’s newfound consciousness despairs because it doesn’t have a soul. When it discovers the traditional First Nations belief that everything has a spirit, it is comforted, and wants to learn more about the history of First Nations people. Of course, the knowledge proves too great a sorrow to bear and the AI deletes itself, an act that calls to mind the suicide crisis amongst First Nations youth. This idea returns in “Mr. Gizmo,” a story about a boy contemplating suicide after experiencing great loss. He has a gun in his hand when a toy robot, beloved in the boy’s childhood, speaks up and talks him out of it. In “Lost in Space,” Mitchell, a First Nations man alone on a space station, struggles to process the death of his grandfather while totally disconnected from the Earth and his people.

It is a quality of Taylor’s work to leave you with not one lasting thought but three or four, and he brings a healthy dose of levity to this collection along with more solemn moments. Each of these stories addresses broad human experiences like loss and identity, topical issues like the importance of seeing First Nations people represented in all fields, while also having fun with robots and spaceships. Indeed, “Superdisappointed” is pure fun as it follows Kyle, the world’s first Aboriginal superhero, throughout his day. Yet, it’s also one of the most effective stories of the collection, achieving Taylor’s goal of expanding the definition of First Nations literature in the most straightforward manner possible, simply by casting an Indigenous man in the role of superhero.

—Nora Decter