Reviews

Poetry Review by Allison LaSorda

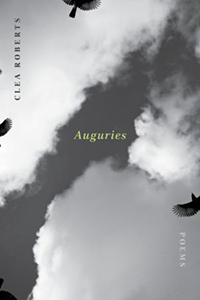

Clea Roberts, Auguries (London: Brick, 2017). Paperbound, 104 pp., $20.

I recently had the good fortune to visit the Yukon Territory, and briefly glimpsed the northern setting at the forefront of Clea Roberts’ collection, Auguries. The clay cliffs, the rushing Yukon River, and the density of wilderness that figures in the territory make up an intense and, at times, unforgiving landscape that provides Roberts’ quiet, tender poems with a background of rich layers and movement.

I recently had the good fortune to visit the Yukon Territory, and briefly glimpsed the northern setting at the forefront of Clea Roberts’ collection, Auguries. The clay cliffs, the rushing Yukon River, and the density of wilderness that figures in the territory make up an intense and, at times, unforgiving landscape that provides Roberts’ quiet, tender poems with a background of rich layers and movement.

The speaker introduces us to Auguries: “I’ve decided to speak, / to release certainty, / to take winter’s ravens / as my rowdy clerics.” The first poem sets the mood and intention of the book. There’s an admission of how language can be fluid and unreliable and also a sign of preoccupation with local corvine birds, who are plentiful and furtive, disruptive and comforting, at once. The sections within Auguries, defined by their foci, fluctuate in length: short, episodic talks, long multi-part poems, and more structured lyric poems. Roberts poems are highly visual, tracking the environs of her home and wider area; she names bird species and local flora with ease, and at times the listing of the unfamiliar is poetic in itself, while the interpretation of such scenes remains vague.

I particularly lingered on the winter-themed portions of Auguries. A Yukon winter at once seems stunning and challenging; in “Cold Snap,” the speaker admits, “I want to be / a winter person; // I like the way / it implies / improvement.” Certainly, the speaker looks to the narrative conventions that focus on northern life: for example, resiliency amid the elements, and having the privilege to choose what is, for many, an unconventional or more difficult lifestyle. Still, winter in Auguries provides more than a backdrop; instead, it seems to have a character of its own. The page breaks between sections (and recurring images of Whiskey Jacks) felt significant, white space as a pause, a moment to sustain. Winter is, if not intrusive, haunting. In my reading, descriptions of winter landscape gave room to absorb the grief poems, and winter offered a welcome respite compared to the urgency of other seasons. Winter’s harshness forces reflection, and the frozen stillness preserves emotions that arise.

The author has, in the process of writing this book, both become and lost a parent, and so mourning and the domestic figure prominently in this collection. In a suite of poems for her daughter, Roberts is candid. The stereotypical impression that a child’s birth is only a time of joy is complicated here: the loss of a former, solitary identity, a sense of isolation, confronting mortality, are undercurrents in these poems. Grief is written with similar complexity. Though the specifics of loss aren’t provided in these poems, the impact is present. Rather than being explained away, or resisted, it is presented with acceptance, even resignation: “This is what it’s like to forgive and yet remember,” she writes. Daily chores—the grim task of starting a car in deep winter, spring planting, child rearing, preparing meals—are what remain reliable, essential tasks for survival and coping with forward momentum and the persistence of memory. As the speaker says in “Spring Planting”: “It doesn’t matter what you use to dig. It doesn’t matter if it’s an act of forgetting or remembering.” Many of the poems are startlingly spare—deceptively so, as their impact deepens with repeated visits. Whether intentional or not, certain pieces have the sensibility of a mantra. Perhaps this is because there are some refrains in this book, repeated attempts to define grief: “Grief is a slow river, never freezing to the bottom... Spooked horses in a storm and you can’t find your coat.”

Auguries are signs of what will happen in the future—omens. An augur, then, is an interpreter of such omens. It remains somewhat unclear to me what, exactly, the omens are. The speaker often searches within the immediate for answers that may not reveal themselves. In “Epoch,” she says: “If there was a moon / it didn’t tell me anything / about myself.” My sense is that we are deeply within the present moment with the speaker. Rarely do the poems carry themselves away to imagining or theorizing. In “The Way a Winter Is Measured,” she writes: “And whether / I refer to calendars or mercury, / only a hard-packed path / along the clay cliffs / will measure the distance I have travelled / through my bright, ambiguous grief.” The speaker is clearly tied to her distinct environment. The idea of human-made measurements for temperature or time feels disingenuous to the process of grief. The desire for real connection after a loss seems to weave a thread between this and other poems; maybe, then, the speaker is looking for signs that connect her to something bigger. Outside of the personal, the wilderness remains real, tangible, and accessible.

In the section titled “Morning Practice,” in which poems are named for yoga poses, I expected that the internal, the sensation of one’s physical body, would’ve been central; instead, the external—more specifically, anything wild or natural—is held onto for symbolic weight. Through the morning practice of yoga, the body alternately feels as an antler, a field mouse under a palm, the weight of a cord of wood, the wind. These are delicate, crafted meditations, but I craved a more substantial sense of the body in the context of a book centering on grief and physical loss. In “Tree Pose,” the speaker says, “It’s necessary to sway a little when the wind shifts,” an admirable quality, to remain flexible to and aware of what external elements (challenging as they may be) require.

Across the collection, the word consider appears frequently. It echoes across the variations of themes and subjects that Roberts explores. To consider consideration, I felt it was important to acknowledge the variants of the word’s meaning: to think carefully, typically before making a decision; to think about and be drawn towards; to regard someone or something as having a specified quality; to look attentively at. The poems of Auguries thoughtfully touch upon each definition, and don’t make demands. Instead, they offer glimpses of distinct distances and proximities, possibilities worth considering.

—Allison LaSorda