Reviews

Fiction Review by Tracy O'Brien

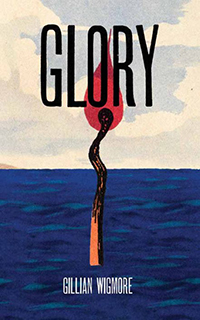

Gillian Wigmore, Glory (Picton: Invisible, 2017). Paperbound, 200 pp., $19.95.

In her debut novel, Glory, Gillian Wigmore shares with us the story of three powerful women in their struggle to escape their pasts and build a future in “back of beyond” northern British Columbia. Fort St. James is a remote town, in this novel a world unto itself that traps inhabitants, surrounding them with unforgiving wilderness and mountains. This is also a story about a vast lake, and how it figuratively and literally swallows those living around it. The lake looms large in these characters’ lives, shifting the weather and providing solace, beauty, and, too often, death.

In her debut novel, Glory, Gillian Wigmore shares with us the story of three powerful women in their struggle to escape their pasts and build a future in “back of beyond” northern British Columbia. Fort St. James is a remote town, in this novel a world unto itself that traps inhabitants, surrounding them with unforgiving wilderness and mountains. This is also a story about a vast lake, and how it figuratively and literally swallows those living around it. The lake looms large in these characters’ lives, shifting the weather and providing solace, beauty, and, too often, death.

In Survival, Margaret Atwood writes “Nature is a monster, perhaps, only if you come to it with unreal expectations or fight its conditions rather than accepting them and learning to live with them.” The monster in Glory is the lake, which Fort St. James’s citizens have mythologized as an almighty force that lures people with its sublime beauty, solitude, and resources, but kills with indifference. The lake draws boaters, fisher people, drinkers, and walkers. When it freezes “it shifts and cracks, unreliable and ruthless.” Fort St. James’s lake governs its citizens’ lives: “First thing they teach you when you’re a baby: ‘You’re on the water when the water goes black, you get off, quicker’n quick.’” Wigmore writes her characters such that their resistance to the struggles in their personal lives is manifested in vicious weather, wind, and waves that threaten lives and remind people of the importance of love and survival over all else.

The novel is written in the first person, but the narrator of each chapter changes to a different member of the community, or to the “Chorus” variously representing individuals or some group of speakers. The constant switching occasionally makes it challenging to follow the continuity of the story and, particularly, the timeline. It is difficult at times to determine whether a given part of the story is continuing linearly, or is a flashback or flash forward. The structure of Wigmore’s novel is that of a song, and music ties the characters’ stories together thematically. She writes in the notes accompanying the novel that the songs her parents listened to are the “inspiration for Glory and Crystal’s music” and Wigmore’s masterful imagery and rhythm create melody in her prose. Thus, while the character switching in each chapter can be confusing, it also contributes to the sense of a performance. Each chapter is comprised of a soloist delivering their rendition of Glory’s life and the events in the novel, and these solos are tied together by the “Chorus.”

It is unclear, however, to whom these characters are telling their stories, or why. This uncertainty can be overlooked as the writer’s choice to reveal a long narrative through a tapestry of short pieces; it is an interesting choice because it tells us something about the nature of how and what truths emerge, if any, when details differ and biases exist between individual reports of the same event. The form becomes a little distracting to the reader when, at one point in Part 3, the “Chorus” is identified as a writer using the journalistic first-person-plural voice. The chapter in question is subtitled “Ruth Harmer, notes toward a news article, never written.” This otherwise absent character is an unnecessary addition that weakens the narrative by shifting attention away from the story and towards resolving whether the novel is Ruth’s compilation of reports or not, who she is, and where she came from.

Inspiring and powerful women throughout the book, Renee, Crystal, and Glory are silenced at the end of this novel. Wigmore states that she “wanted to talk about women” and “how there are old hard-and-fast roles but not everyone fits into those ready-made roles.” Atwood identifies the “Rapunzel Syndrome” as a pattern “for “realistic” novels about “normal” women in which the main character is metaphorically imprisoned by her social conditions: i.e., the family “society says she must not abandon.” According to the fairy tale, of course, Rapunzel is rescued by a man. In these “realistic” novels, “the Rescuer’s facelessness and lack of substance as a character is usually a clue to his status as a fantasy-escape figure.” In Glory, the women make choices about whether or not to accept their circumstances in Fort St. James and settle with the men in their lives.

I read the silencing of Renee, Crystal, and Glory in two ways. First, the shift in focus from the female character finding balance in her life through her independence to finding it through a satisfying relationship with a man is simply Wigmore’s effort to bring the story in line with a traditional, happy ending. She has explored the dynamics between Renee, Glory, and Crystal, and followed them on their respective journeys to find a home and identity in this unforgiving wilderness and world of men. She finds that her characters are only at home in committed relationships with “good” men from their pasts, and to resist those relationships only leads to hardship. Hence, their struggles and self-explorations become trivialized almost as teenagers acting out against the societal restraints in which they live. Their protests are corrected when they return to the mature, sensible, reliable men in their lives.

I am hopeful that my second reading is more accurate, that the silencing of these powerful women as a means to their peace and happiness is the result of society’s patriarchal reliance on the normativity of a monogamous heterosexual relationship in which the male protects and comforts the female who reciprocates with her loyalty and gratitude. It is dissatisfying to see powerful female characters only find happiness through men; however, it is a painful reality that society deems women’s power as unruliness that must be subdued. Wigmore captures all of this in her stunning, raw prose and a fierce narrative that is irresistibly readable.

—Tracy O'Brien