Reviews

Fiction Review by Clarissa Fortin

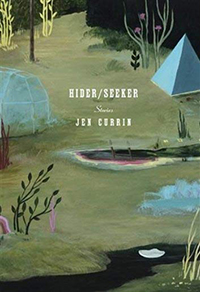

Jen Currin, Hider/Seeker (Vancouver: Anvil, 2018). Paperbound, 224 pp., $20.

In a world of noise, of endless news cycles, pundits and demagogues, Jen Currin’s debut short-story collection is a source of welcome stillness and respite. The book is Currin’s foray into short fiction after four published books of poetry. Hider/Seeker is aptly titled: its pages are populated with characters longing for retreat, or seeking out revelations. Currin’s characters, mostly queer women, journey to isolated cabins, and uncomfortable dinner parties, explore unorthodox Buddhist centres, and lonely bathhouses. Her prose is spare and clean and her stories can be concise snapshots of existence, surreal expressions of psychological states, or, sometimes, a fascinating mix of both. Characters hide from each other, from themselves, seek peace, and seek connection. As the narrator of the opening story “The Charlatan,” says, “I tried to look at each stranger’s face as if I knew them.”

In a world of noise, of endless news cycles, pundits and demagogues, Jen Currin’s debut short-story collection is a source of welcome stillness and respite. The book is Currin’s foray into short fiction after four published books of poetry. Hider/Seeker is aptly titled: its pages are populated with characters longing for retreat, or seeking out revelations. Currin’s characters, mostly queer women, journey to isolated cabins, and uncomfortable dinner parties, explore unorthodox Buddhist centres, and lonely bathhouses. Her prose is spare and clean and her stories can be concise snapshots of existence, surreal expressions of psychological states, or, sometimes, a fascinating mix of both. Characters hide from each other, from themselves, seek peace, and seek connection. As the narrator of the opening story “The Charlatan,” says, “I tried to look at each stranger’s face as if I knew them.”

Hider/Seeker encourages the reader to look into the faces of a wide cast of strangers and know them. Stories vary in length and style, the longest being twelve pages and the shortest just a few paragraphs. Currin primarily concerns herself with the emotional minutiae of ordinary people living ordinary lives but she also introduces the occasional levitating woman, angel, ghost, or lizard man. While “Up the Mountain” and “Hider” are narrated by the same character, the rest of the pieces overlap thematically rather than narratively, and often mirror or respond to each other. Failed relationships, alcohol addiction, misogyny, meditation, domestic violence, and grief—these elements surface over and over in various forms.

Meditation and self-reflection come up again and again as plot points and central themes in Currin’s stories. In “The Garden of Vows” and “Up the Mountain,” forms of Buddhist meditation help the protagonists confront pain and act with greater compassion towards themselves and others. However, in “Hide and Seek,” the search for stillness and fulfillment takes on a surreal and perhaps sinister tone as the protagonist falls in with a mysterious cult. In these stories, the path to self-knowledge can be fraught with false prophets and danger. At other times, stories directly contrast each other. “The Sisters and the Ash” is a fairy tale about three sisters who overcome incestuous patriarchal violence with the help of an old crone and some jewelled knives. The father himself meets a biblical fate, turning to dust as his daughters live on in a conclusion that is hopeful and empowering. However, “Snake in the Grass” follows former alcoholic Shannon, the middle of three sisters who are all dealing with the lifelong repercussions of their father’s sexual abuse. In “The Sisters and the Ash,” women are protected from sexual violence by crones and knives, whereas, in Shannon’s world, it seems that a cruel history of misogyny and violence may be doomed to repeat itself.

Not every story is strictly heartbreak and trauma. There are complicated joys and triumphs too. The reunion of two ex-wives in “Third Beach” is lovely to behold, even though their relationship seems ultimately doomed. There is the great surging power the young protagonist feels at the end of “Girlfriend/Boyfriend,” when she is finally able to stand up to a boy who is after all “only a little bit tall and marginally handsome”—but she finds the courage to do this at a terrible moment.

Currin often leaves her characters in the midst of their own indecision and pain. She resists the urge for a conclusion or transformative character arc. While this can be frustrating, it’s also comforting. Currin taps into the rhythms of a life as it’s lived, allows the reader a glance into that life, and then moves on. In “The Rash,” for instance, she leaves her protagonist in the midst of his deep depression. “Seeker” finds its central character isolated in a cabin struggling through the fourth day of a looming thirty-day retreat. While many of these stories take us to the annals of sadness and regret, they’re always elevated by Currin’s prose. She finds beauty in moments of stasis and stillness. “I had always loved hinges—the places where death and birth meet,” muses one protagonist, post break-up. “Orange-brown leaves rotting in a puddle as snow begins to fall, waking at dawn on an overnight train.”

The stories are strongest when the mundane and the wondrous live side by side, as in “Up the Mountain” and “Hider.” “Up the Mountain” follows Misaki, who arrives at the Kanda Monastery while grieving the loss of her father. “Hider,” the final story of the book, returns to Misaki seven months later when a domineering, power-hungry new student named Mark arrives at the monastery. Currin’s gift for subtlety is on full display here. Mark is made sinister entirely through the feeling he creates in Misaki: “Often while walking in the woods or sweeping the hall I think I see him out of the corner of my eye—but when I turn he’s not there,” she observes, “There is something shadowy about him, even when he’s standing in bright sunlight.” This build-up to perceived danger followed by an unexpected catharsis provides a deeply satisfying conclusion to the collection. The author does not pass simple judgements or leave us with easy conclusions about any of her characters. Mark might learn, he might transform. Or he might not. The same goes for every single hider, seeker, and survivor Currin leaves on the precipice.

—Clarissa Fortin