Reviews

Poetry Review by Karen Schindler

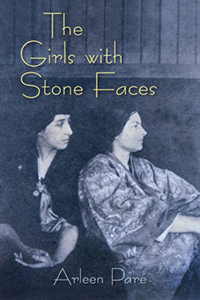

Arleen Paré, The Girls with Stone Faces (London: Brick, 2017). Paperbound, 104 pp., $20.

When I saw The Girls with Stone Faces listed in Brick Books’ fall catalogue last year, it was an easy choice. I’d been awaiting Arleen Paré’s next collection, plus there was the arresting cover portrait by Robert Joseph Flaherty: “In the photograph the two sit / gazing left, to the east, composed in that way, / profiled in kimonos and loose-knotted scarves” (“Having Been Made to Abandon Their Lives”). Who were these “girls with stone faces,” captured so beautifully in bromide-blue? Although previously unaware of Frances Loring and Florence Wyle, it didn’t take me long to get up to speed. Paré draws the once-renowned sculptors back into focus so compellingly—touring us through their lives, love, and art—that I’ve become an ardent admirer of Loring and Wyle, and I suspect this has been a common reaction to the collection.

When I saw The Girls with Stone Faces listed in Brick Books’ fall catalogue last year, it was an easy choice. I’d been awaiting Arleen Paré’s next collection, plus there was the arresting cover portrait by Robert Joseph Flaherty: “In the photograph the two sit / gazing left, to the east, composed in that way, / profiled in kimonos and loose-knotted scarves” (“Having Been Made to Abandon Their Lives”). Who were these “girls with stone faces,” captured so beautifully in bromide-blue? Although previously unaware of Frances Loring and Florence Wyle, it didn’t take me long to get up to speed. Paré draws the once-renowned sculptors back into focus so compellingly—touring us through their lives, love, and art—that I’ve become an ardent admirer of Loring and Wyle, and I suspect this has been a common reaction to the collection.

An epigraph-intro provides the backdrop: the two women met as art students in Chicago in 1906, then moved to Toronto where they worked side-by-side in their deconsecrated church studio-home for almost sixty years. They built solid reputations as Canadian sculptors, while advocating for other artists and, most notably, expanding the role of women in art. Paré’s five room-themed sections present their story in a loose chronology, with emphasis on biography, ekphrasis, and politics of the time.

Poems in the first “rooms” highlight the women’s contrasting styles. Loring was the flamboyant extrovert, sculptor of memorials and political statues, lover of cigarettes and scotch: “not reluctant in love Frances loved mud clay… //… the way life is almost always about to take flight… //… she loved being boss phone calls and her red velvet cape” (“Frances Loved Florence”). Wyle was the tough-minded introvert, excelling at portraits and torsos: “Reluctant and yet / Florence did love… /… loved the wind rough / across blue Midwestern plains… //…The unadorned female form, / she loved and was smitten. Despite or because of the breasts” (“Florence Loved Frances”).

While the extent of their partnership was (not surprisingly) never declared, their private relationship provides context for some of Paré’s most beautifully crafted lines: “They hallow their life in this church, / stumble over clay feet and empty arms in the night. // Do they wake in wholeness into each other’s arms? / Does the sun dash cobalt, shards of red, gold on the spread?” (“This Church is a Ghazal”).

In first-person poems, Paré takes us more immediately in hand to share in her narrator’s own discovery. The closing lines of “The National Gallery: Unguarded I Would Have Caressed Every Surface” illustrate Paré’s consistently imaginative attention to wording: “… I knew only distillate awe / a welter of bliss / I could only memorize the shapes sanctified the room a basilica a concrete / space that transcended the concrete.” “Basilica” points to the high-ceilinged, hushed museum room where the narrator is brought to a standstill, and also the sculptors’ church-home, twice sacred because of the sanctity bestowed anywhere art is created, or love shared. “Welter of bliss” captures the emotional chaos (welter) of being overwhelmed by art, with a subtle side-serving of bodily impact (welt) that implicates the harsh physicality of sculpting. “Distillate” references both the pure intensity of the narrator’s experience and the creation process itself—be it a figure emerging from the sculptor’s stone, or an essence extracted into words by the poet.

In the section “Rooms without Enough Room,” tensions are ratcheted up as Paré addresses the difficulties the women would have encountered. “How Heavy Art 1” places us on the scaffolding with Loring, at work on her stone lion beside the new Queen Elizabeth Way: “her gloveless hands, the groan / of the planks as she shifts / her hips, the slip / of the chisel in sleet.” We are also treated to a poem series based on the looming next sculptor-of-choice: “It’s not that they will die. / They will die: early winter and a revolution / already rummaging the streets… // It’s Henry Moore, / the holes he sculpts inside their minds, their bodies, art, / their peace” (“How Art Works”). Paré’s five ekphrastic studies of Moore’s females—monumental in size, or missing feet or arms—deftly capture how this pervading modernist influence would have run smack up against Loring’s and Wyle’s “art should above all be beautiful” aesthetic.

The section “Last Rooms” focuses on loss (both women died in 1968, within weeks of each other), including our struggles with transience: “Angels, of course, go missing, stables fall / brick by brick into the street, // Is there anything that will not?” (“All Things Removed”). But Paré’s answer to this question is what resonates throughout. She offers eloquent argument for art’s fluid existence, suggesting that artists not only preserve but set something new in motion: “Point, line, and depth: these form the dimensions of sculpture. / There is a fourth, which is time, elastic, supple, / hard to predict… // The process working in either direction. / Between the two women” (“Technicalities of Neoclassical Sculpture in the Beaux Arts Tradition”). There are the two directions of Loring’s and Wyle’s craft: building up poured casts; carving away bronze and stone. There is the two-directional time-bridge that their work has created, for Paré, and now for any reader of this collection. And like Paré’s gallery-wandering narrator who realizes, “What I love about you… // is how you / love me back” (“Torso 4”), we are reminded of the two-way emotional exchange with art which, when we’re lucky, can occur.

—Karen Schindler