Reviews

Poetry Review by Mitchell Parry

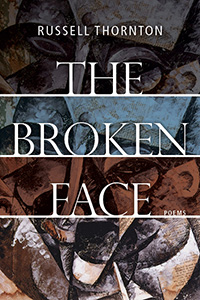

Russell Thornton, The Broken Face (Madeira Park: Harbour, 2018).

Paperbound, 95 pp., $18.95.

The cover of North Vancouver poet Russell Thornton’s seventh book, The Broken Face, features details from Umberto Boccioni’s 1913 mixed-media piece, Dynamism of a Man’s Head, an Italian Futurist work that simultaneously shatters and reconstructs a human head in an effort to capture how it changes in response to movement. Or, rather, how our perception of an object changes when it moves. It’s a strange image, nearly cubist in its geometrical reorganization of an ordinary and miraculous thing (what could be more ordinary and more miraculous than a face—human or otherwise?). It’s also the perfect image to grace the cover of Thornton’s first poetry collection since the Griffin-Prize-shortlisted The Hundred Lives (Quattro Books, 2014).

The cover of North Vancouver poet Russell Thornton’s seventh book, The Broken Face, features details from Umberto Boccioni’s 1913 mixed-media piece, Dynamism of a Man’s Head, an Italian Futurist work that simultaneously shatters and reconstructs a human head in an effort to capture how it changes in response to movement. Or, rather, how our perception of an object changes when it moves. It’s a strange image, nearly cubist in its geometrical reorganization of an ordinary and miraculous thing (what could be more ordinary and more miraculous than a face—human or otherwise?). It’s also the perfect image to grace the cover of Thornton’s first poetry collection since the Griffin-Prize-shortlisted The Hundred Lives (Quattro Books, 2014).

In an online interview with Malahat Review volunteer stephen e. leckie, Thornton claims that “a great poem occurs when language and experience meet—and become indistinguishable. Of course, the experience is extraordinary—and involves in itself a union of thought and feeling. And of course the language is extraordinary.”

That sense of language and experience “meeting” is central to the success of The Broken Face; in fact, I would argue that it is what allows Thornton’s poetry to come into being. For example, “Xmastime Dancing” opens with “two children [who] are giving an impromptu performance,” dancing to music in a local mall. Watching, the speaker feels his chest “tighten on a sudden darkness inside. It is real, / death is this close, and is nothing if not joy.” In the next line the poet confirms what we have suspected all along: the children are his children rather than random kids dancing in a mall; the generic children have become specific, personal, identifiable. Suddenly, surprisingly, the “two elderly people holding onto each other” and watching the dance are revealed to be the speaker’s deceased grandparents, at which point this extraordinary experience meets language that is, truly, extraordinary:

They have come back,

they have followed the electric current

along the never-ending looped pathway

of a circuit and arrived at snowflake stars

and a bright space where my kids move hypnotized

by “Jingle Bells” and “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer”—

and the living world is strange to them now

but warm and exquisite, as a food court meal

was once a banquet.

It’s a lovely image—particularly that “food court meal”—that initially seems to elevate the ordinary to the extraordinary but instead reveals how extraordinary the everyday really is.

This gesture of revelation accounts for the collection’s general tone of (what the publisher’s press material refers to as) the sacramental. The Broken Face is teeming with “holiness”: holy moments, holy objects, holy people—especially the poet’s children, who offer startling revelations and questions throughout the four unnamed sections that make up the book. Part I focuses on violence, criminal behaviour, recklessness; the bad choices it recounts are superseded, ultimately, by the arrival of a child, before whom the speaker “can do nothing, nothing other than kneel // and offer up what he is in the animal present, / a body a carrier of time” (“Week-Old Son”). Part ii takes up that idea of the self as “a carrier of time,” walking a fine tightrope between the past, full of familial schisms and disappointments, and the future (in the form of the children who embody its promise and its dangers); in the present, the speaker becomes the pivot point that links the two generational realms. Or a portal, perhaps, like the title subject of “Copper Door,” in which the speaker revisits a home built by his grandfather, the house’s signature “copper-clad entranceway” both calling him in and barring his entrance. Thornton uses this image brilliantly:

The door would open and come to a quiet close,

unlike the old man who died in pain, his bones crumbling

within him where he lay in his care home bed

uttering a metallic growl through gritted teeth.

The “metallic growl through gritted teeth” seals the poem for me, snug and precise as the door at the centre of the poem.

Part iii widens the focus, devoting itself to North Vancouver, where Thornton grew up and now resides. Although the poems in this section acknowledge the aspects of the area for which North Vancouver is known (the inescapable mountains, Lynn Canyon), Thornton is more interested in those parts of city life that don’t make it into postcards—the local Safeway, the wildfires looming just over the mountains, the “fearless, lit” homeless men who regularly race shopping carts down the district’s steep hills (“Cart Riders”). Again, Thornton’s attention is drawn to the sacramental: “Who will drive his cart straight to paradise? / Who will know God in the air rushing past him?”

The book’s final section is, in some ways, less successful. Its individual poems are all strong, all are places where extraordinary experience and language meet, but it feels as though they don’t hang together as convincingly as do the other sections. Nevertheless, there are some terrific poems in this final part of the book, including the title poem, with its chant-like repetition that makes emphatically human the faces—broken and whole—of the tried and convicted.

The Broken Face confirms Russell Thornton’s place as an important, extraordinary Canadian poet. In fact, reading this book made me want to start writing poetry again. High praise indeed.

—Mitchell Parry