Reviews

Nonfiction Review by waaseyaa'sin Christine Sy

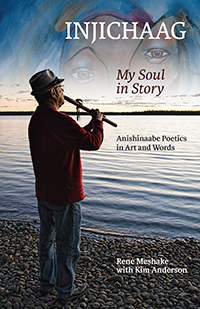

Rene Meshake with Kim Anderson, Injichaag: My Soul in Story, Anishinaabe Poetics in Art and Words (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba, 2019). Paperbound, 304 pp., $24.95.

As a student of my Anishinaabe culture, poet and creative, and assistant professor who has learned from Anishinaabe “Techno Elder” Rene Meshake, I was thrilled to learn of his latest publication and was eager to embark on learning from it. The work of a multi-media artist and educator who has previously written and illustrated children’s books entitled Blueberry Rapids (2008) and Moccasin Creek (2009)—books that exist lovingly in my family library—Injichaag is Elder Meshake’s first creative nonfiction book. Easily situated within the fields of Indigenous Culture, Literatures and Languages, Oral History, and Philosophy, its most salient disciplinary contribution will be to Anishinaabe Studies.

As a student of my Anishinaabe culture, poet and creative, and assistant professor who has learned from Anishinaabe “Techno Elder” Rene Meshake, I was thrilled to learn of his latest publication and was eager to embark on learning from it. The work of a multi-media artist and educator who has previously written and illustrated children’s books entitled Blueberry Rapids (2008) and Moccasin Creek (2009)—books that exist lovingly in my family library—Injichaag is Elder Meshake’s first creative nonfiction book. Easily situated within the fields of Indigenous Culture, Literatures and Languages, Oral History, and Philosophy, its most salient disciplinary contribution will be to Anishinaabe Studies.

Through her Introduction and Epilogue, Rene’s adopted daughter and Cree/Métis scholar, Kim Anderson makes her own unique contribution by illuminating his life vis-à-vis the philosophy of the Anishinaabe life cycle; and she closes with an emphasis on Indigenous vibrancy and futurity. Simultaneously, this book is historicized within Canada’s colonial structure and processes such as the residential

school system, and as such readers may expect the content to engage pain and trauma. However, where Elder Meshake is obviously shaped by his experience as an Ojibway boy and man in Canada, the soul-in-story that he documents for the present and future focuses on life-giving Anishinaabe ways, the significance of relationships, endurance, good life, and creating. This is not so much a purposeful partitioning off of painful subjects as it is a broad teaching in itself: Anishinaabe life, lifeways, personhood, and the future are much more dynamic and omnipresent than ongoing colonization and its effects.

Identified as both memoir and life story, Injichaag rests at the nexus of memoir and autobiography due to its feeling and intimate reflections on life experiences as well as its references to particular periods of his life and historical events. The field of Indigenous literature is continuing to unfold and Indigenous memoir as a particular genre has not been as fully articulated as has Indigenous autobiography. A more

fitting description would be Indigenous “autobiographical” books, because the parameters of and methods employed in writing “the Indigenous self” as it exists over time are fluid, creative—perhaps “undisciplined”—and are often marked by historical, political, economic, social, and environmental confluences. Recent examples of Indigenous manifestations of one’s life in writing and/or in audio version that, like Meshake’s memoir, defy prescriptive expectations include Lindsay Nixon’s nîtisânak (2018), Terese Mailhot’s heart berries (2018), and Tanya Tagaq’s Split Tooth (2019). Indigenous life stories, or stories from life, often include the self as a part of a larger whole— a family, a community, a circle of relations, a nation. They likewise include personal engagement with the natural and supernatural world. Meshake’s energizing and multi-genre approach, and the vibrancy and spirit conveyed in his particular method, is a signpost of what Cree-Métis scholar Deanna Reder refers to, in her research on Indigenous autobiography, as an Indigenous intellectual tradition.

Injichaag is also a significant addition to the almost non-existent library of Anishinaabe men’s autobiography and autobiographical books, or texts. These include Kahgegagabowh George Copway’s The life, history, and travels of Kah-ge-ga-gah-bowh, a young Indian chief of the Ojebwa Nation (1847), Herb Nabigon’s The Hollow Tree (2006), and the digitally published “teachings” of Paul Buffalo through the University of Minnesota Duluth (last updated, 2019). If readers know of more, please let me know! Uniquely—and standing out from these other writings— where grandmothers often figure in the life stories of Anishinaabe men as relatives, Rene describes the significance of his grandmother’s influence in his life as a relative operating within matriarchal society. Intended or unintended, this qualification is a powerful naming, or renaming, of Anishinaabe forms of governance which have long been invisibilized through colonial processes.

Focusing less on what this dynamic book is and more on what it does, Elder Meshake begins with an invocation which is followed by a brief orientation to the significance of storytelling. Comparing oldtime storytelling functions and ways to today’s, he says, “There’s no more guys like that. Today we have these storytelling festivals and

people that travel around. I sometimes do that, but I’m always telling stories just as a part of my life, too.” From this, then, the significance of doing storytelling and keeping that going within Anishinaabe ways of being is an important objective. In this way, Rene embarks on storytelling across seven themes: nurturing, warnings, loss, protection and transition, recovery, healing through art, and regeneration.

Anishinaabemowin (the language) is presented as stand-alone short definitions rendered through the translation of syllables. It is also conveyed through what Rene refers to as his method of “word bundles.” Where dictionaries abound, Anishinaabe oral histories include Anishinaabe words with translations or entire translated texts, and Anishinaabe language educators create new materials with the intent of revitalizing the language; Rene’s “word bundle” approach teaches concepts he considers significant by enriching them with nuanced stories that convey worldview. His creativity and joy with the language and with teaching it resonate with the writing of Anishinaabe poet, scholar, language educator, and language-maker, Margaret

Noodin. Indeed, Meshake’s word bundles are like sacred little packages that explode with meaning and possibility.

Employing multiple methods to convey his intentions, Rene’s book is accessible in large part due to the short vignette-like stories and language entries as well as visual art. Readers will engage poetry, oral history, visual art, genealogy, teachings, and the two aforementioned salient approaches to language translation presentations. With the varied genres and myriad topics included, thematic flow and organization is, at times, discombobulating; however, like a jazz song the structure works, and the teachings work their magic. It is evident that Rene’s life-force is shining and the generative power emanating through his writings is created to benefit anyone interested in learning about life through an Anishinaabe lens.

—waaseyaa'sin Christine Sy