Reviews

Poetry Review by Heather Milne

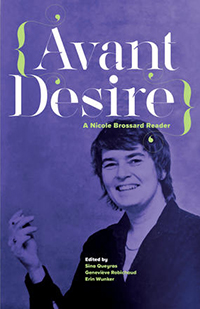

Avant Desire: A Nicole Brossard Reader, edited by Sina Queyras, Geneviève Robichaud, and Erin Wunker (Toronto: Coach House, 2020).

Paperbound, 320 pp., $26.95.

Editing a volume of the selected works of Nicole Brossard is a monumental task. Brossard has published almost fifty books of poetry, essays, and fiction in a career that spans more than five decades. She is one of Canada’s and Quebec’s most accomplished, prolific, and innovative writers and she has worked with dozens of translators to render her work accessible to readers in at least nine languages. This skilled trio of editors—Sina Queyras, Geneviève Robichaud, and Erin Wunker—has proven itself to be up to the task of compiling a collection that reflects the depth and scope of Brossard’s writing. Avant Desire: A Nicole Brossard Reader is an engaging, challenging, and comprehensive collection.

Editing a volume of the selected works of Nicole Brossard is a monumental task. Brossard has published almost fifty books of poetry, essays, and fiction in a career that spans more than five decades. She is one of Canada’s and Quebec’s most accomplished, prolific, and innovative writers and she has worked with dozens of translators to render her work accessible to readers in at least nine languages. This skilled trio of editors—Sina Queyras, Geneviève Robichaud, and Erin Wunker—has proven itself to be up to the task of compiling a collection that reflects the depth and scope of Brossard’s writing. Avant Desire: A Nicole Brossard Reader is an engaging, challenging, and comprehensive collection.

Avant Desire will appeal to readers new to Brossard’s writing and those already familiar with her work. Readers encountering Brossard for the first time in Avant Desire will glean a sense of her versatility as a writer; the poetic, philosophical, and political questions that have engaged her over the years; the language play, radical experimentation, and intellectual collaboration that have always been key features of her work; and the centrality of translation to the way her writing is received in English. Readers already familiar with Brossard’s work will experience the pleasure of recognition and rediscovery, but they will also encounter material they have not read before and will read familiar works in new ways since the selections gathered in this volume are set in conversation with each other across decades, genres, and translators through meticulous editorial arrangement. The selections span Brossard’s career ranging from early works initially published in the early 1970s to pieces only recently translated into English and published here for the first time.

Selections excerpted from longer works for inclusion in anthologies can sometimes feel truncated and decontextualized. The pieces in Avant Desire do not, for the most part, succumb to this problem because many of the excerpts are quite generous— entire poems, essays, or chapters from longer works are often reprinted in full. This allows most selections to stand on their own. The excerpted texts inevitably lose

some of their original context, but they also gain new contexts through their resonances with other selections in Avant Desire. The editors have arranged the book in five thematic sections: Desirings; Generations; The City; Translations, Retranslations, Transcollaborations; and Futures. Each section includes work written in a variety of genres from various stages of Brossard’s career. These thematic groupings provide a structure for the book and highlight concerns vital to Brossard’s writing. It should be noted, however, that all five of these themes weave

their way throughout the book to a large degree; part of the pleasure of reading Avant Desire lies in tracing the resonances that occur across the book and throughout Brossard’s oeuvre.

Placing newer work alongside older work highlights both the ways in which Brossard’s writing has changed over the years and the ways in which she has always been ahead of her time, and perhaps this is where the “Avant” in the title becomes most prescient. Reading some of the earlier pieces from the 1970s, one is struck by just how urgent this work still feels. Brossard’s poetic experimentations in texts like

French Kiss (1974) and These Our Mothers (1977) still feel contemporary; her poems and essays that have overtly feminist and lesbian themes still feel radical. Yet Brossard is also always “of” her time as a writer who engages with the politics, the eros, and the aesthetics of the present, whatever that present might be. As she writes in “Lorem Ipsum,” “I have always wanted to be of my time, meaning that very early on I assigned myself the task of understanding the world I live in. What are the values, the standards, the social and literary currents that have transited through me?” In a spirited, salon‐style conversation, included in this volume, between Brossard and fellow writers Catherine Mavrikakis and Nathanaël, Brossard explains: “I write on two pages: one page is the page of desire and utopia, and another page

which describes what is happening in the status of women, among women. Everything that has been stolen from women since the beginning of history. For me, these two pages operate at the same time.” This dual focus is a defining feature of Brossard’s writing and one of the reasons why her work is so enduring and engaging; she offers incisive political critique, while simultaneously articulating possibility, hope, celebration, community, and desire through radical literary experimentation.

With the exception of one piece that Brossard wrote in English, each selection in this volume is translated from French to English, so the reader is accessing Brossard mediated through translation. Occasionally, as in the poem “Sous La Langue / Under the Tongue,” we are provided with the French version followed by the English translation, allowing us to move between French and English and track the translation for ourselves. For Brossard, translation is not simply a matter of finding the equivalent English words for the original French words: it is an act of transferring the vitality of the text into a different language. Translation is a dynamic site of possibility and experimentation, and a space of sustained creative collaboration between translator and author. As Brossard writes in “Suddenly I find Myself Remaking the World,” a remarkable essay on translation that concludes this volume, “what we read in a poem is its energy, and that is what is most difficult to translate, because energy is what radiates from calibration, the expenditure or restraint in a text; it is this incandescence, the fine silk of living, that must be translated. Energy is the form of the living poem, meaning constantly shifting, which one has to pin down without seeming to.”

By my count, Avant Desire features the work of twenty‐four different translators ranging from Brossard’s earliest translators, including Larry Shouldice, Barbara Godard, and Suzanne de Lotbinière‐Harwood, to more recent ones, including Oana Avasilichioaei, Katia Grubisic, and Anne‐Marie Wheeler. Many are poets themselves: Erin Mouré and Robert Majzels, Oana Avasilichioaei, Caroline Bergvall, Angela Carr, and Katia Grubisic, among others. The book includes a section of Barbara Godard’s 1983 translation of These Our Mothers, or The Disintegrating Chapter directly followed by Erin Mouré and Robert Majzels’ 2019 retranslation, SeaMother: The Bitteroded Chapter. While the retranslation echoes Godard’s, it is also markedly different, illustrating just how significantly translation actively shapes meaning, and how, as Mouré and Majzels explain, a different “voice and tenor” arise

from reading and translating these texts in 2019. The editors include two dates following each selection in the book, the date of original publication and the date of translation, underscoring the sense that the translation and the original are related but distinct works. The volume also includes playful transcollaborations between Brossard and anglophone poets Daphne Marlatt and Fred Wah, as well as a homophonic translation by Charles Bernstein and an anagrammatic translation by Bronwyn Haslam. These experiments in translation highlight the creative, generative potential of translation as a site of linguistic play and experimentation, as well as its centrality to how anglophone readers encounter Brossard’s work.

Avant Desire: A Nicole Brossard Reader will serve as the definitive selected works of one of Canada’s and Quebec’s foremost experimental writers and feminist thinkers. Editing a volume of this scope and magnitude entails sustained and careful engagement on the part of its editors. It is a trans‐generational feminist collaboration and a labour of love. Sina Queyras, Geneviève Robichaud, and Erin Wunker have created an impressive book that pays fitting tribute to Nicole Brossard.

—Heather Milne