Reviews

Fiction Review by Rhonda Mullins

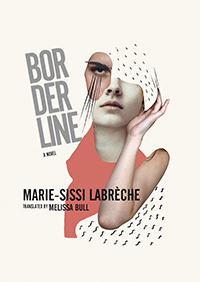

Marie-Sissi Labrèche, Borderline, translated by Melissa Bull (Vancouver: Anvil, 2020).

Paperbound, 152 pp., $18.

When I cracked the cover of Marie‐Sissi Labrèche’s novel Borderline, I could have sworn I heard a scream. And indeed, it was a scream of anguish that started on page 1 and ended on page 143.

When I cracked the cover of Marie‐Sissi Labrèche’s novel Borderline, I could have sworn I heard a scream. And indeed, it was a scream of anguish that started on page 1 and ended on page 143.

Originally published in French under the same title in 2000 by Les Éditions du Boréal, Borderline had to wait twenty long years to be translated to English, something thankfully undertaken by Anvil Press and author, poet, and translator Melissa Bull. It is only right that the book be available to English‐speaking audiences, given the chord it has struck across countries and on the screen. Borderline has appeared in German, Russian, Dutch, and Greek, and was made into a movie by the same name, earning Labrèche a Genie Award for best adapted screenplay. Borderline tells the story of Sissi, a seemingly feral young woman who is numbing the pain from her childhood through casual sex and less casual alcohol, turning to physical intimacy and recklessness to avoid emotional connection. Her erratic, destructive behaviour is explained through flashbacks to her trauma‐filled upbringing. Raised by a mother who suffered from mental illness and made repeated attempts at suicide, Sissi starts to believe that she is the source of her mother’s illness and indeed of all ills, egged on in her shame-fuelled delusion by her vitriolic grandmother. From the age of eleven, she is left in the sole care of her grandmother, a haranguing presence who lashes out regularly and without warning, threatening Sissi that she will end up thrown to the wolves, with a concomitant range of dire fates, from foster homes to sexual predators.

As we are ushered back and forth between the present day and her childhood, we gain insight into how Sissi’s outrageous, at times exhibitionist, grown‐up conduct has the same drivers as the behaviour of a child who finds no emotional safety no matter where she turns. And having learned that being taken care of comes at the price of emotional abuse, pain, and indignity, Sissi decides it is better to go it alone.

Labrèche effectively captures what happens when childhood trauma is carried into adulthood, where the chaos and violence that was once on the outside colonizes the inside and becomes trapped in the mind and the body. Sissi is diagnosed with borderline personality disorder, an illness driven by fear of abandonment that leads to her rage, impulsiveness, and mood swings, and her need to push people away. “I’m borderline,” she says. “I’ve got a problem with limits. I can’t tell the difference between inside and out. Because my skin is on backwards. Because my nerves are tightly wound. I think everyone can see inside me. I’m transparent. I’m so transparent I have to scream so people can see me. I have to make a racket for people to take care of me. That’s why I don’t know when to stop.” And she doesn’t stop, careening through the pages from men who disgust her to women who beguile her, always just beyond reach of the hands held out to try to save her. As her grandmother comes to the end of her life, Sissi unravels, with a glimmer of hope that in the unravelling she can start to heal.

The novel includes helpful endnotes to explain some of the more arcane aspects of Québécois language and culture to English readers, but then lapses into a Quebec that doesn’t exist, with doctors making house calls, direct hotlines to the emergency room, and male gym teachers helping little girls get undressed and changed for gym class. And for a book anchored in gritty realism, glib humour does not fly, such as when young Sissi calls for help after yet another of her mother’s suicide attempts, chatting with the operator about her mother’s uncanny Marilyn Monroe imitation. The dissociation of the moment is believable, but the execution, if only for the anachronism, is less so. But these are minor quibbles that do not detract from the overall effect, which is disturbing. On first reading, thinking I had heard the odd lapse in voice, I stepped back to consider that perhaps that was the point, to hear the wounded child surface in the adult who is tearing down everything around her.

English‐speaking readers will feel they are in good hands with Melissa Bull’s translation. When words are spit rather than said, as Labrèche’s are in Borderline, finding the right tone to convey the pain and rage while avoiding lapsing into caricature and verbal slapstick is a challenge. The rawness of a novel like Borderline would have been difficult to translate. But Bull manages to match spit for spit with Labrèche, perhaps a skill honed in channelling Nelly Arcan in translation, a woman who was conversant with pain. Or perhaps it is simply that a scream of anguish is understandable in any language and loses none of its resonance some twenty years on.

—Rhonda Mullins