Reviews

Poetry Review by David Eso

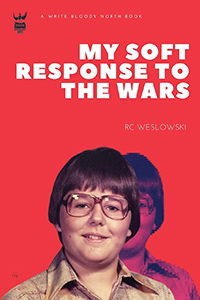

RC Weslowski, My Soft Response to the Wars (n.p.: Write Bloody North, 2021). Paperbound, 92 pp., $20.

Rarely does one encounter a debut collection by a veteran poet. My

Soft Response to the Wars offers that opportunity because its author has

made his writing public primarily from stages and through microphones

since the late 1990s. RC Weslowski is the kindly, clowning silverback

of Vancouver’s slam‐poetry and spoken‐word scenes. His

bombastic profundities and zany glee have won him a role as a kind

of Robert Munsch for adults: a healer who plays seer and storyteller

for the overgrown kids living within a certain set of underground literary

tinkerers.

Rarely does one encounter a debut collection by a veteran poet. My

Soft Response to the Wars offers that opportunity because its author has

made his writing public primarily from stages and through microphones

since the late 1990s. RC Weslowski is the kindly, clowning silverback

of Vancouver’s slam‐poetry and spoken‐word scenes. His

bombastic profundities and zany glee have won him a role as a kind

of Robert Munsch for adults: a healer who plays seer and storyteller

for the overgrown kids living within a certain set of underground literary

tinkerers.

The book’s publisher, Write Bloody North, has set out to preserve

spoken‐word artists in book form. In that, it joins in the mandates of

Write Bloody Publishing (of Portland, Oregon) and Write Bloody UK

(established 2020). The American company launched in 2004 and has

made more than 100 books available. The independent Canadian

imprint now has five titles to its credit, including RC Weslowski’s

promising addition to the starting line‐up. Write Bloody North’s previous

releases are by poets Ian Keteku, Lucia Misch, Titilope Sonuga,

and Brandon Wint.

In My Soft Response, edited by Stuart Ross, Weslowski appears as

only a shadow of the prominent oral poet. On stages, embodied recitations

and vocal acuity amplify the writerly craft that forms one part

of his artfulness. Familiarity with his penchant for comedically

inflected silences as well as his expertise as a voice artist may have

bolstered my enjoyment of the book. Those elements of his poetic talent

floodlit my reading—inescapable resonances after seeing his infectious

performances at many arts festivals and poetry events over the

past twenty years or so.

Much of Weslowski’s book concerns the battle to conquer stifling

silence with vital expression. He sees his North American society

plagued by secrecy and falsity. It is “a vampire empire” fed on media

staples like “bad porn and sitcoms.” In that context, creative utterance

becomes a daring, necessary attack from the fringes. Repressive limits

on communication receive vivid and clever descriptions: “an inability

to express / the crushed grape in your chest.” Even so, the sense of

frustration with muted speech and broken connections repeats across

poems to the point where I wanted to hear more of the direct counterforce

that is RC Weslowski (a stage‐ and now also pen‐name). To

dramatize expressiveness and its failures, the book continually returns

to terms for mouths, lips, throats, breaths, voices, and words (spoken

or withheld). The poet feels he has “a fox in [his] mouth” but must spit it out to say so. Weslowski courageously strives to overcome the

strains corrupting communication, which seems to me more valuable

than any primer on the problem of “Shackle Hearted” inarticulateness.

For this poet, making meaningful connections through language risks

a kind of incoherence (“a sacred union of confusion”) that reveals his

exuberant, even unusual spirit. He writes of a “tarantula dairy assassin,”

“Ut Ut Igboo Weasels,” “knuckle‐crumpling disco weavers,” and

“belching on a pickled trumpet.” These are dizzying formulations by

a writer emancipated from the banal, and I found that aspect of My

Soft Response deeply absorbing. And yet, to use a military metaphor

inspired by the book’s title, I sometimes wanted to encounter fewer

targets and more ammunition.

Weslowski’s Response presents outraged and outrageous voices but

also its promised softness. The poet sounds out a spare style in portions

of the book that address personal trauma and healing. Take these aphoristic

lines, seemingly on music: “the only thing you’ve ever loved / that’s

never hurt you.” Consider the poignant image of a boy’s hands “not

folded” but “knotted in prayer.” Pain comes across when the poet shifts

to his quieter tones. Simultaneously, the book’s recurrent commentary

on voicelessness takes on new depths in the blacklight of an unfolding

“history of abuse.” The poems testify to post‐traumatic flourishing;

their flourishes of language are more salvific than decorative. One character

in the book, Floyd Jones, speaks freely. Jones colours his bluecollar

monologue with elaborate and obscene cussing. But his is no

mere foul‐mouthed chin‐waggling. The poet sees Jones’s string of curses

as holy, especially when “compared to the profanities of commerce and

/ the blasphemies of human self‐righteousness.” And so, the enmity

between veiled quietude and gritty volubility is waged on emotional

and political terms in this Soft and not‐so Soft Response. Here, individual

and society suffer or heal together; on that ground, “your joy / is a revolutionary

act / your love, your rage.” RC Weslowski’s battle cry

unleashes “a spirit of fuck you and fuck yeah” that marks his book as

an underground offering, one both furious and loving.

Given the poet’s current track record, we may wait decades before

receiving another print collection to consider, puzzle over, and enjoy.

Meanwhile, the Canadian literary scene can continue to benefit from

his projects outside publishing. These include his regular Wax Poetic program on Vancouver’s Co‐op Radio, his Oh No Not Another Podcast podcast, and his live poetry performances.

—David Eso