Reviews

Poetry Review by Cara-Lyn Morgan

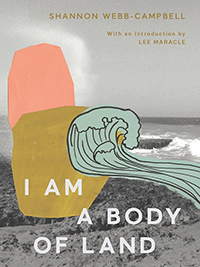

Shannon Webb-Campbell, I Am a Body of Land (Toronto: Book*hug, 2019). Paperbound, 72 pp., $18.

Unlearning. This is the undercurrent of Shannon Webb-Campbell’s I Am a Body of Land and a response to her controversial and now infamous collection Who Took My Sister? Released in a flurry of accolades, the book was then promptly pulled from circulation amidst concerns of breach of Indigenous Storytelling Protocol, and the fallout from that experience could have tempted the writer down a truly different path. Where many may have simply licked their wounds and plowed forward, or, worse, refused to acknowledge the damage caused by their best intentions, Webb-Campbell revisits, rather than abandons, the highly criticized work, examining ways of reparation, acknowledging past errors, and attempting to acknowledge self-education as an Indigenous woman and an artist speaking the stories of a community in the midst of generations of pain and healing.

Unlearning. This is the undercurrent of Shannon Webb-Campbell’s I Am a Body of Land and a response to her controversial and now infamous collection Who Took My Sister? Released in a flurry of accolades, the book was then promptly pulled from circulation amidst concerns of breach of Indigenous Storytelling Protocol, and the fallout from that experience could have tempted the writer down a truly different path. Where many may have simply licked their wounds and plowed forward, or, worse, refused to acknowledge the damage caused by their best intentions, Webb-Campbell revisits, rather than abandons, the highly criticized work, examining ways of reparation, acknowledging past errors, and attempting to acknowledge self-education as an Indigenous woman and an artist speaking the stories of a community in the midst of generations of pain and healing.

It strikes me that this collection is not an apology. It is an attempt to understand the root of past mistakes, and to move forward causing no further harm. It is an ecdysis, the sloughing off of old skin and the growing into a new one. The result is beautiful and aware, a timely exploration of cultural and generational trauma, identity, and purpose. It is an act of humility, admonishment, and personal and artistic growth. The collection is an intersecting of art and catechism—a new forum for poetry to question its intrinsic role in healing and all the ways in which our own path toward self-understanding can bring unintended pain.

This book is an honest desire to speak the past, for Webb-Campbell to understand her own colonized mentality, and to acknowledge the ways in which this colonization informs part of her Indigenous understanding. “… L’nu Neuptjeg. / I’m Mi’kmaq forever … I am a translation of a translation.” She walks the space between Indigenous and Settler storytelling with both delicacy and confidence.

I Am a Body of Land addresses questions of how to make amends, how to show that we have heard and learned from the past in a way that allows us to move forward without repeating our mistakes. Webb-Campbell navigates communal pain—its impact on the individual—and begins to examine generations of colonial scar tissue, to de-colonize herself and, by extension, her art.

Webb-Campbell does not dwell on the past, but rather navigates through personal and national narratives to uncover wounds complex, unhealed, and largely unexplored. There is an air of caution throughout—“be careful with this story you now live”—that acts partly as wisdom being passed along, but also as an internal mantra for the speaker, that the reader cannot help but adopt. It is a reminder of how easily mistakes can be repeated, how insidious are the harms of the past, how crucial it is to remain vigilant. She pointedly addresses storytelling protocol, drawing on responsibility which extends beyond poetic licence and accepts the difficult reality that not all stories are hers to tell.

Like the past, the poems are fraught with moments of desperation and loss: “we are living in a trauma state / our capital is your pain.” And also like the past, they contain snippets of sweetness, understanding, and human connection.

Highly confessional and self-exploratory, the collection moves in a clear arc of understanding and evolution: from sterile, cautious, and self-deprecating language—“You say I’m not / Indian enough, like I don’t already know”—to descriptions of the most intimate connection—a child chewing a piece of gum from the mouth of her drunken relative, an act of innocence underlain with the dark awareness that if she does not remove the gum her loved one may choke on it in their sleep. “Our love is unlearning. Our only living treaty.”

The early poems are lined with discomfort and insecurity teetering on despair, yet just as the collection becomes uncomfortable to read, we see the poet suddenly owning her voice again, shifting from sparse language to repetition and musicality, from confession into dance. It is a swift and timely shift, the moment the old skin is discarded and the new skin feels air for the first time.

The closing poems are lighter structurally and rhythmically, and though Webb-Campbell maintains the awareness of caution and understanding of the lessons addressed in the earlier work, this part leaves the impression of a speaker who truly understands the struggle and that the process of exploration was worth it. The end pieces are a testament to optimism: “we are made of oceans . . . we are liquid ceremonies. We are sky.”

“You know trauma lives . . . . You are not divided from your body . . . . You know the land will outlast us all.” This is a short book, at times easily read despite the weightiness of the subject, due to the poet’s skill and command of language. It can be read in a single sitting, mused over, and enjoyed. It is also the work of a truly aware writer, a formerly admonished child, someone seeking to undo past harms while acknowledging and exploring the colonization which led to her mistakes in the first place, the story of a woman learning to unlearn. I Am a Body of Land is memory, humility, and a celebration of truly good poetry.

—Cara-Lyn Morgan