Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Chelsea Rushton

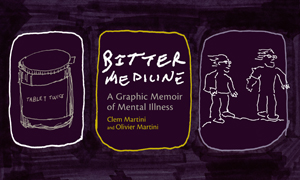

Clem Martini and Olivier Martini, Bitter Medicine: A Graphic Memoir of Mental Illness (Calgary: Freehand, 2010). Paperbound, 260 pp., $23.95.

If someone asked me what schizophrenia is, I would be able to say that schizophrenia is a mental illness that has any number of symptoms including hallucinations, delusions, paranoia, slurred speech, disorganization, depression, and withdrawal. But do I know what that actually means for the people who are diagnosed, or for their families, or for the medical staff that need to care for them? If I were asked to explain the complexities of the disease and how it can completely change the lives of those who are faced with it, I wouldn’t have a clue where to start. In Bitter Medicine: A Graphic Memoir of Mental Illness, Clem and Olivier Martini have done an admirable job of explaining.

The Martinis were a regular family: Mom, Dad, four sons, a dog. They ate dinner together and took summer vacations. Clem writes that “the biggest thing to understand is that we were nothing remarkable.” But in 1976, youngest brother Ben was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and then, ten years later, brother Olivier (Liv) was told he had it also. This book is Clem’s written account of his family’s threedecade struggle to cope with and understand mental illness, presented alongside Olivier’s illustrations of his experience, which are at once delightful and disquieting. Together, the brothers have created something that is not a textbook, nor a diagnostic manual. Rather, Bitter Medicine is charming and accessible even before it’s opened: with unconventional dimensions and Olivier’s primitive, almost feral-looking pictures on the cover. These also appear liberally throughout the book as portraits, scenes, and comic strips. Not only do they break up the text, they provide ballast as they lend insight and atmosphere that simply cannot be otherwise articulated.

Clem approaches the subject from several angles: the book begins with a poignant, personal account, in which readers are welcomed from the start:

I thought I had our future lives mapped out. Liv, my second oldest brother, unearthed more dinosaur bones than anyone else. From this evidence I concluded that he was destined to become a palaeontologist. (Though he was also the only one among us who had discovered flint arrowheads on several occasions, so there was, I assumed, the outside chance he would become an archaeologist.) Nic, the eldest and our undisputed leader, could identify every tree, bush, or cactus from a single seed or needle. He would, I was certain, secure employment as one of those park naturalists my family so admired. …I wanted to write. I wasn’t sure where you applied for a job like that, though, or what credentials were required. I thought maybe I’d work in a zoo instead. I liked animals.

A trusting relationship is formed between the writer and the audience, and this allows Clem to maintain an unbroken dialogue with readers, as though he is confiding in us. Rather than being disconcerted by this, as I am in most other cases, I found myself thankful.

It is because this text took me by the hand, guiding me through any number of situations I might not encounter otherwise, that the book’s interlude, “The Circles of Hell,” is so effective. It occurs after Liv has been diagnosed with schizophrenia, when it becomes evident that he simply cannot hold a job the way other folks can, and before anyone can see in the dark to find some kind of solution to this problem. “To appreciate Liv’s anxiety surrounding being unemployed,” Clem writes in his small introduction to this section, “you have to understand that for those with mental illnesses, beneath the surface of society there exists another dimension, and it is always, always waiting.” It begins with diagnosis, and cycles through joblessness, alienation from family and friends, homelessness, and finally imprisonment. “The Circles” is written exclusively in the second person in order to place the reader exactly in that uncomfortable position of someone diagnosed with a mental illness.

Coming out of “The Circles” readers are further faced with what was (and was not) being done, at the time of Liv’s diagnosis, by the government, the hospitals, and the mental health providers, to integrate patients back into their communities, and what is still lacking some thirty years later. Clem bitterly states that “underfunding of psychiatric services is prevalent, systematic, and blithely accepted across the country.” Not only does he bolster this statement with research and statistics, but he also encourages his readers to go to their local hospital and try to find the psychiatric ward, and to venture into their communities and locate the integrated mental health support services. “Don’t worry if it takes a little time,” he says. “It’ll turn up eventually, secreted in some anonymous, out-of-the-way site.”

While the stats are indeed grim, and the funding inadequate, and Liv’s journey through various pharmaceutical treatments is perhaps sadder still, this narrative ends on an encouraging note. Liv takes to a daily regimen of walking and moves in with Mother. They help each other and drive each other crazy, but somehow these small things make all those other big horrible things seem not so big, or not so horrible. It’s a relief for us to know that maybe there is one tiny slice of relief here. This solace does not come with any guarantees, however, nor does it come without a grave warning that things must change. “The system is a mess,” Clem says. “Those in the highest levels of our health care system must stop shutting their eyes, pretending that nothing is wrong, pretending that psychiatric services are receiving adequate support.” Bitter Medicine doesn’t aim to make readers feel better when we finish reading, or safer, or as though we are off the hook for something. In fact it’s exactly the opposite: we’re made aware of the very real injustices concerning those afflicted with mental illness. By virtue of the fact that we all co-exist together, that injustice extends to everyone, and the truth is simply that “we all deserve better.”

—Chelsea Rushton