Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Eric Miller

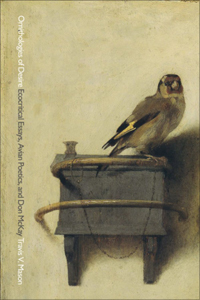

Travis V. Mason, Ornithologies of Desire: Ecocritical Essays, Avian Poetics, and Don McKay (Waterloo: Wilfrid Laurier, 2013). Hardbound, 306 pp., $48.99.

Rare is the poet in Canada who has not felt Don McKay’s kindness. “Kindness” is too abstract a quality. Say rather that many have experienced McKay’s many kindnesses. More significantly, it is a rare poet who has not been touched and inspired by Don McKay’s evolving example. Travis V. Mason’s book Ornithologies of Desire: Ecocritical Essays, Avian Poetics, and Don McKay is about McKay’s work; it is not by McKay himself; but one of the pleasures that Mason offers is anthological. He quotes McKay deliciously. It remains a challenge and a delight to read once more “the clearing is the wild ancestor of the room of one’s own,” and to be reminded that starlings on their perches behave and sound like “high-school wise guys.”

Mason’s book features fourteen essays, loosely disposed under their assigned rubrics. Take Chapter Seven, called “Birdsong.” In the course of such a chapter, Mason reliably offers lots of exciting, appropriately airy speculations: we learn that bird music and human music may have co-evolved. Mason chooses, moreover, and gathers, and piquantly dispenses to us, his happy readers, many gratifying facts. A brown thrasher has at its disposal fully two thousand distinct songs. To perform its song, the Bewick’s wren uses one hundred per cent of its breath: by contrast, human speech demands two per cent. Ravens transport water to their nestlings via their soaked plumage. Mason usefully refers us to an apposite literary character, refining the field guide in this respect. He calls this creature “the Bumbling Birder,” and uses for his holotype McKay’s folksy, tender, keen, though ironic, persona. Mason honours McKay with the seriousness this poet and his poetry deserve.

Nevertheless, as I read Mason’s book (in Toronto, in Parry Sound District, and on Vancouver Island), I found myself picking quarrels with it. In truth, Mason’s book would seem to harbour two souls in its breast. It manifests a bifurcated aim. One thrust of Mason’s argument would secure the significance and worth of McKay’s poetry and project. But Mason, an academic essayist, as opposed to a practitioner of belletristic writing, too often makes everything gracelessly explicit: “Positioning McKay’s writing about birdsong alongside and against the lyric tradition, I argue that McKay’s attention to aural wilderness, particularly birdsong, iterates an attentive relation to the nonhuman world by modelling an active, respectful style of listening.”

The second thrust of Ornithologies of Desire concerns the conduct of the university and of university life. Reduced to its exiguous skeleton, this polemical wing of the book urges the professor (or aspirant professor) to leave the office and learn in the field. This advice, praiseworthy enough in itself, appears in the guise of certain recommendations pressed vehemently on an abstraction called “ecocriticism.” Ecocriticism gradually accrues the attributes of an allegorical character—like McKay’s Bumbling Birder, but decidedly less compelling: “Such an ecocriticism would manoeuvre between and among various disciplinary approaches to the physical world while accommodating a complex set of challenges to anthropocentric models of the universe.” This overlooks how McKay’s own verse, with the Bumbling Birder persona, admits as its first premise and its last, too, the predicament of incarnation: there is no alternative for us to being embodied as humans—if you will, we are damned to anthropocentricity. Mason also claims that his ecopoets “undermine the unquestioned authority of anthropocentric language and knowledge in order to elevate the standing, in ethical terms, of other-than-human-beings.” Poets do nothing of the kind. They write poetry.

Mason confesses that he shifted his scholarly focus from history to ecocriticism. Though the ideas of Linda Hutcheon influence his argument, history is not one of the “various disciplinary approaches” that he brings very steadily to bear on McKay and nature writing. Nevertheless, opportunities to look at history open in Ornithologies of Desire. Mason mentions a soldier who birded while he fought in the midst of one of the Iraq wars. What is the relationship, the reader is reasonably prompted to ask, between the two Bush-Hussein conflicts and the “linguistic imperialism” that Mason excoriates as a defect of imaginative writing? Mason only says that here is proof that birding is among the most democratic of pastimes. His lack of proportion drifts toward the comic. Tens of thousands die: the indignant Muse of Satire stirs. Wars are imperialistic (not just “linguistically imperialistic”) in their nature, whatever their participants say. It is important to acknowledge the salience of satire to the case, and then to move beyond it. The Bumbling Birder does have a real, surprising, even confounding place on a planet of incessant strife—our planet. Carefully read, McKay himself would begin to disclose it. A hundred thousand corpses, a human being with a pair of binoculars: they do and they should belong together. How? What is the role of the perpetual amateur—the gauche, befuddled, diffident, ridiculous, inquisitive ornithologist—in the era of the surveillance state? Mason is perhaps too concerned to professionalize “ecocriticism” to ponder further. Instead, he recommends to writers and readers what he calls “species specificity,” meaning we should know what we are talking about (this is an American goldfinch, not a yellow warbler; boneset, not lady’s tresses). He also recommends (in the words of Robert Bringhurst) “knowing, not owning”: the refinement or suspension of a “desire to possess.” Very well. But Mason’s cozy, prosaic structure approximates earlier models from which he might wish to distance himself: the complacencies of physico-theology, the smugness of extinct sermons. Human nature affirms that the incessant recommendation of virtue will precipitate into its thorough abandonment.

Because ecocriticism is an equal partner with the Bumbling Birder in Mason’s narrative, the effect of Ornithologies of Desire is repeatedly to demonstrate that McKay has good intentions. It is true: McKay does. Mason has admirable intentions, too. But what about the poetry? Mason quotes McKay primarily for “content.” It is as though we wished to apprehend the “content” of a Bewick’s wren’s music, in a false isolation from other factors. Don McKay has a great, perhaps accidental precedent in Goethe. He, too, explored poetry of desire and of renunciation. Goethe insisted on the daemonic—the eruptive, the uncontrollable— as an abiding factor in poetry and in science. McKay’s definition of wilderness—“the capacity of all things to elude the mind’s appropriations”—has an affinity with Goethe’s “daemonic.” “All things,” after all, translates as “Pan.” Call it “wilderness” (as McKay does), Pan, the Muse: Mason’s style of reasoning fails to propitiate, or even really to acknowledge, this spirit.

—Eric Miller