Reviews

Fiction Review by Karen Schindler

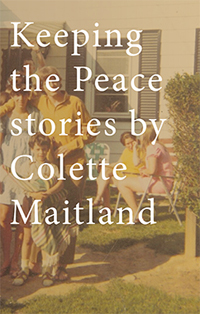

Colette Maitland, Keeping the Peace (Windsor: Biblioasis, 2013). Paperbound, 240 pp., $21.95.

In her short fiction debut, Keeping the Peace, Colette Maitland presents us with nineteen stories set on her home turf of small-town Eastern Ontario—in and around Smiths Falls, Kingston, Brockville—with focus on the girls and women who live there. An interweaving of characters throughout the stories, not uncommon in short fiction collections, might suggest an emphasis on community. However, Maitland’s light hand with this—the way a character from one story drifts through another in such a marginal way—serves to underscore her interest in her characters’ insular struggles.

The females in Maitland’s stories are all wrestling with something—grieving, in denial, neglected, lost. Her protagonist is either tackling a current impossible situation—such as shopping for a car to replace the one a son was driving when killed in a prom-night crash—or she’s been trying for years to move on from the past, one that might include a teenage-self in the bathtub, a drunken father, and an unlocked bathroom door. Maitland’s women are stuck—paused on thresholds. (It’s a theme the author subtly emphasizes by ending a handful of stories with a character literally at a doorway.) Can they find escape? love? vision? a way to get un-stuck? In the best of these stories, the answers aren’t explicit.

Reading this collection, it’s easy to be reminded of Alice Munro’s analogy of a short story being more like a house than a road, where you go inside and explore the rooms, “wandering back and forth and settling where you like.” Munro’s story-as-house metaphor works well here. Maitland manages to create a “what do I see?” momentum, rather than “where is this going?” She’s also good at creating tension-filled actual rooms for her readers. In “Children at Play,” it’s an upstairs bedroom at an annual Hallowe’en house party, where just-out-of-high-school Chrissie is nursing her baby while an ex-boyfriend lingers in the bedroom doorway and her lost-cause husband’s drunken voice drifts up from the backyard. In “Faith and Joy,” it’s the office of the town doctor, where thirty-eight-year-old Faith lies supine on the examination table while her seventy-year-old doctor, who’s known her all her life, assesses her post-partum body and pointedly avoids her post-partum mind.

In addition to scene setting, Maitland also displays a knack for handling endings. Yeats said that a poem “comes right with a click like a closing box.” Although the Yeats quote does not necessarily refer to a poem’s conclusion but rather to the writer knowing when a poem is finished, the metaphor extrapolates well to short fiction endings. It addresses both the need for there to be some sense that the story has been brought into concord as well as the idea that this should happen when we haven’t quite finished checking out every corner of that box. More often than not, Maitland nails this elusive “click.” A couple of her less impactful stories feel like they have overly-orchestrated conclusions, however, these are in contrast to more subtle presentations such as “Catch and Release.” In this story, pregnant, stay-at-home mom Gail is talked into a girls’ getaway at a fishing lodge with her ex-addict cousin, Lou. Upon return from their soul-baring weekend, Lou takes it upon herself to stir the waters of Gail’s marriage, as Gail is unable to confront her husband with her suspicions of infidelity. The closing scene, in an upstairs bathroom, is one of morning sickness and confession, and ends with this: “Gail closes her eyes for a moment. Resting her cheek against the cool lip of the toilet bowl, she listens as the tank refills with water until the sound of the water rising stops with a satisfying thunk.” The “thunk” provides a solid, corporeal, “swallow hard and move on” closing, nicely tying in to water-related themes of pressure, drowning, and surfacing, but also adequately oblique. It manages to leave the bathroom door ajar for us.

A similarly effective “click” (more like a buzzing in this case) can be felt at the end of the title story. In “Keeping the Peace,” Sybil, single mother and military widow to soldier Martin, relocates to a smaller town to shift the wayward course that her fourteen-year-old daughter seems intent on following. As Sybil begins work at a new casino, daughter Gwen finds a job at a local motel, which brings its own set of temptations. The closing scene involves a return to a more innocent dynamic between mother and daughter, with Gwen crawling into her mom’s bed: “Sybil’s gaze is drawn up and over Gwen’s shoulder, to the urn that sits atop her dresser—Martin’s remains. And not for the first time, she imagines a miniature Martin trapped inside there like a genie, waiting for the right set of hands, the perfect string of words to set him free.” The tensions within and between mother and daughter, in abeyance but not gone, are concisely represented by a very-much-alive vibrating presence in the urn. At the same time, the closing image refocuses our attention, giving new weight to Martin’s presence throughout the story. It’s a fine execution of Yeats' “coming right."

—Karen Schindler