Reviews

Fiction Review by Corinna Chong

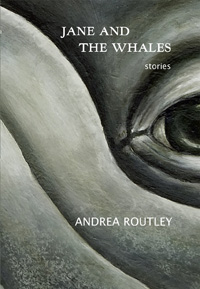

Andrea Routley, Jane and the Whales: Stories (Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin, 2013). Paperbound, 160 pp., $18.95.

While the stories that make up Andrea Routley’s debut short story collection, Jane and the Whales, are wildly diverse in subject matter, plot, and theme, the concept of deception becomes their connecting thread. Reading this collection is akin to navigating a carnival funhouse, coming up against wacky mirrors, dead ends, and moving hallways that take the floor out from beneath your feet. The narrators of these stories consistently deceive the readers, leading us to empathize with the protagonists’ apparently universal conflicts, only to later reveal the deeply unsettling extent of their moral failings. At the same time, the central characters deceive themselves, so firmly lodged in their ways of seeing the world that they remain blind to their own desperation.

While the stories that make up Andrea Routley’s debut short story collection, Jane and the Whales, are wildly diverse in subject matter, plot, and theme, the concept of deception becomes their connecting thread. Reading this collection is akin to navigating a carnival funhouse, coming up against wacky mirrors, dead ends, and moving hallways that take the floor out from beneath your feet. The narrators of these stories consistently deceive the readers, leading us to empathize with the protagonists’ apparently universal conflicts, only to later reveal the deeply unsettling extent of their moral failings. At the same time, the central characters deceive themselves, so firmly lodged in their ways of seeing the world that they remain blind to their own desperation.

Most striking about this collection is Routley’s ability to stretch her protagonists, gradually turning them inside out over the course of each story. In “Habitat,” Ray is a recently divorced father whose fifteen-year-old daughter is eager to shed her childhood as she excises old possessions from her bedroom. Lana’s mounting disinterest in her guinea pig, Bubble Gum, and her rejection of her place in her father’s home comes off as adolescent immaturity and selfishness in the beginning, and Ray’s misguided attempt to build a new-and-improved habitat for Bubble Gum reveals how difficult this transition is proving for him. It seems that Ray is being neglected, too, as he admits to Lana, “I’ve been thinking about Bubble Gum. Do you still love her?” exposing his fear that Lana’s love for him has also dissolved. Parallel to this narrative, Ray grapples with the problem of a fox that has been scavenging through his garbage, a habit that bothers Ray not for the mess, but because “He couldn’t stand to see a wild thing living like a transient.” In a surprising yet carefully paced turn of events, Ray transforms from being a likeness of the guinea pig—tame, naively loving, and an unfortunate casualty of Lana’s carelessness—to a reflection of the fox, who has become, unbeknownst to itself, a pathetic bottom-feeder, living off the unpalatable scraps of the past.

“Other People’s Houses,” the most memorable story of the collection, follows a similar structure. Bent on distancing himself from “the boiled wieners of his own childhood, minute rice, and fluorescent orange macaroni” that characterized his working-class upbringing, Tom obsesses over christening his newly purchased “Authentic Italian Brick Oven” by cooking a pork shank roast and holding a dinner party, to which he has invited his bitter ex-wife. Meanwhile, his ten-year-old daughter entertains her friend, Bonnie, who is staying over for the weekend, to Tom’s chagrin. As in “Habitat,” the story begins by encouraging readers to sympathize with Tom, as Bonnie is obnoxious, rude, and appears to have a derelict home life—one that bears striking resemblance to Tom’s when he was a child. However, Routley begins to drop clues over the course of the story that Tom is actually a superficial snob, more concerned with status and appearances than he is about the wellbeing of his daughter, and maintaining a stubborn resolve to see himself as a victim. By the gasp-worthy climax of the story, the sheer magnitude of Tom’s ignorance to his own internal struggles exposes itself, simultaneously shattering his already tenuous bond with his daughter.

The writing is at its strongest when the narrators are given space for careful reflection. “The Things I Would Say” tells of two sisters, who witnessed, and subsequently covered up, the drowning of their childhood friend. The compelling description of the moments following the drowning, as seen through the young narrator’s eyes, has an elegant, dream-like quality, punctuated by the narrator’s shocking, and even menacing, passivity: “I imagined the sturgeon swimming toward her, not as a vague shadow or a flash, but heavy, growing larger, Jurassic, its diamond back glowing brighter, mapping a trail to the other side, here to take her soul, but hitting its head on the log boom, just because she had said that, maybe, and I laughed. I laughed, not at Krista falling, at those other thoughts, and only because I didn’t know what was about to happen.”

The collection begins to lose some of its momentum at around the halfway point, where a few of the stories seem to rely more heavily on the inventiveness of the overall premise than on the strength of the writing. However, the book finishes strong with the title story. The setting of a seedy gay karaoke bar is an unlikely stage for a character like Jane, who only “wants… More. She wants more from this beer, this coaster, that story, this bar. Everything!” She yearns to experience a transcendental disconnection from body and reality, naively convinced that choosing the right song to sing for karaoke will give her the opportunity she needs, even while cheesy throwback songs like “My Way,” “Like a Virgin,” and “Hot Stuff” make up the usual repertoire. Routley explores the imagined feeling of escaping oneself in a fascinatingly polarized way that is, paradoxically, akin to both flying, weightless and untethered, and sinking slowly into the depths of the ocean.

Indeed, the theme of polarization resonates across the collection. These stories all deal, in various ways, with characters that make unexpected connections, but at the same time suffer traumatic disconnections, all the while toeing the line between ordinary and extraordinary circumstances. Routley’s perceptiveness of the subtle magic that underlies everyday life, and her ability to illuminate those subtleties to be fresh and yet instantly recognizable at once, is the standout strength of this collection. As Jane observes in the title story, “It is hard to see the mystical in something so familiar”—a fitting capstone for a collection that manages to achieve just that.

—Corinna Chong