Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Sandra McIntyre

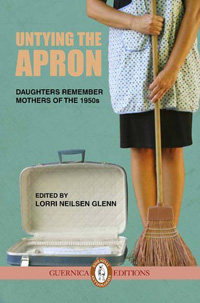

Lorri Neilsen Glenn, ed. Untying the Apron: Daughters Remember Mothers of the 1950s (Toronto: Guernica, 2013). Paperbound, 244 pp., $25.

The apron is an apt symbol that works by association to call up an immediate stereotype: the North American housewife and mother of the 1950s. The apron is her work uniform, signifying her place in the kitchen, the armour she dons to do battle with mess and dirt. It represents the domesticity to which the mother-housewife is tied, whether she puts it on willingly or not. Even the spotlessness of her clothes without the apron reminds us of it. The apron ties hold the apron to her body; symbolically, they bind her to the role. The ties call to mind the drudgery of the work, her lack of freedom to reject the role, the restrictions on her behaviour and on her self-expression, and her socialized passivity—what Simone de Beauvoir called woman’s immanence.

The apron is an apt symbol that works by association to call up an immediate stereotype: the North American housewife and mother of the 1950s. The apron is her work uniform, signifying her place in the kitchen, the armour she dons to do battle with mess and dirt. It represents the domesticity to which the mother-housewife is tied, whether she puts it on willingly or not. Even the spotlessness of her clothes without the apron reminds us of it. The apron ties hold the apron to her body; symbolically, they bind her to the role. The ties call to mind the drudgery of the work, her lack of freedom to reject the role, the restrictions on her behaviour and on her self-expression, and her socialized passivity—what Simone de Beauvoir called woman’s immanence.

Untying the apron, then, is a liberating, transcendent act, one fit for daughters who came of age during the feminism of the 1960s and 1970s. Again and again, the writers in this anthology provide examples of mothers out of apron, doing things beyond the work of providing home-cooked meals and fresh laundry. The untying they do through writing frees their mothers from the stereotype that erases individuality. In Janice Acton’s “The Forward Look,” we see young Janice’s mother with her royal-blue 1957 Chevrolet, not to mention Miss Hopkins, the “woman with grey hair and granny tie-up shoes,” expressing an interest in cars and the car show. In Marilyn Gear Pilling’s “The Sour Red Cherries,” we see mother handling a gun, which she shoots with a squint and “careful aim.” The mother in Deb Loughead’s “The Dirty Blonde in the Yellow Pajamas,” “could never tell off-colour jokes, could never act foolish and impetuous in public, always had to maintain her wifely veneer,” but she could and did tell stories that reveal these parts of her character, the feistiness she has buried.

Published in Guernica Editions’ Essential Anthologies Series, Untying the Apron brings together more than seventy contemporary works of poetry and prose (less than a quarter previously published, most in the 1990s) from well- and lesser-known Canadian literary voices. The anthology opens with Daphne Marlatt’s “Keeping Up.” Marlatt is well known as a writer interested in memory; “I like rubbing the edges of document and memory/fiction against one another,” she says, speaking of her novel Ana Historic, but the sentiment applies to her prose piece “Keeping Up” as well (interview with Sue Kossew of the University of New South Wales). Opening with Marlatt sets the tone for the anthology as an exercise in remembering while cataloguing the expectations placed on women in the 1950s, in particular the ways in which they were expected to judge themselves not to their own standards but to the standards of others. Several poems and prose pieces in the collection follow suit, some presenting women who created, reverted to, or rediscovered their own standards.

Advertisements from the 1950s, reproduced in low-quality black and white, along with a few photographs interleave the sections of the book. The ads also remind the reader of the expectations placed on women to conform to societal standards, though I do wish more care had been taken in reproducing these ads in all their graphic glory. Part of how they work on readers is not only the authority they assume but the cheery “lustre” and sheen with which that authority is imparted.

The mothers of the fifties (as seen through their daughters’ eyes, anyway) are generally not critical of the status quo or engaged in any systemic analysis of oppression. They act out of necessity or compulsion, and do not see their behaviour or decisions as extraordinary. For those who do struggle against the ties that bind, resistance often manifests in the body or in the mind. There are many instances of mothers addicted, “mad,” unstable, sick, or depressed. Often, as Pam Thomas expresses it in her biographical piece, “The Alien Corn,” no one “questioned the smoke of her melancholy.” Occasionally a daughter presents her mother as part of a group, as in Patricia Young’s “The Mad and Beautiful Mothers.” Or a daughter might use her mother’s gendered oppression as an entry point for understanding her own, as in Shauna Butterwick’s “In My Blood”: “We make our own way, walk our own path, not noticing we’re on the same road, caught in the same bind.” But, for the most part, the act of untying is a gentle, personal one. The purpose of untying appears to be one of understanding and coming to terms, as much for the daughters as for their mothers. Few express anger or blame, a wonderful exception being deborah schnitzer’s “Good Mother,” This is not to say a critical viewpoint is lacking, only that it comes not from individual poems or stories but aggregates across the collection. Reading the anthology is a consciousness-raising exercise. The details make the writing good and true. The commonalities of experience make it political. The last section, called “Getting Ready,” I found especially powerful, as would, I expect, any reader contemplating a mother’s life and death.

—Sandra McIntyre