Reviews

Fiction Review by Tim Rogers

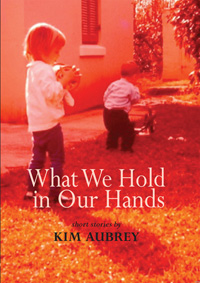

Kim Aubrey, What We Hold in Our Hands (Bradford: Demeter, 2013). Paperbound, 153 pp., $19.95.

This is a collection of ten short stories that are, of sorts, slice-of-life ethnographies. Each is a snippet from the day-to-day lives of a variety of characters, including a young woman navigating between male companions, a man’s efforts to find meaning in his life through watercolour painting, children trying to deal with their mother’s depression, a wheelchair-bound woman longing for a life outside her dingy apartment, and a couple negotiating change to the background of a televised bicycle race. Covering a broad spectrum of the elements of our contemporary lives, the stories deal with transitions, difficult choices, and caring.

This is a collection of ten short stories that are, of sorts, slice-of-life ethnographies. Each is a snippet from the day-to-day lives of a variety of characters, including a young woman navigating between male companions, a man’s efforts to find meaning in his life through watercolour painting, children trying to deal with their mother’s depression, a wheelchair-bound woman longing for a life outside her dingy apartment, and a couple negotiating change to the background of a televised bicycle race. Covering a broad spectrum of the elements of our contemporary lives, the stories deal with transitions, difficult choices, and caring.

Within each of these vignettes there is a constant interplay between time and reflection as various elements from the stories play against each other in complex yet intriguing ways. For example, in “Eating Water” the internal observations of being caught in the undertow of an ocean wave are set against multiple thoughts about the narrator’s parents, creating a whirlwind montage of impressions and reactions. The end result is a fluid insight into the character’s life. The general tone of such complicated interplay is gritty and harsh—no sentimentality here: “When we first moved into this apartment, I hated it. It’s on an ugly street lined with strip malls and car dealerships. If you drive a mile in any direction, that’s pretty much all you’ll see. The building’s a squat, brown rectangle, the elevator lurches and creaks, and everything smells of old meatloaf.” (“Flickers”)

There are also occasional moments of grace and gentility: “Within the low, graying Bermuda limestone wall grows a further wall of pink oleander, bordering the lemon grove. A big arching white cedar stands across from the lemon trees. Under its shade, no grass will grow, and the ground, red from the iron-rich soil, lies bare and soft. A curving gravel path leads up past rose bushes and nasturtiums to a small white house with dark green shutters.” (“Lemon Curl”) But, in the story’s next lines, we are yankedback into Aubrey’s flinty reality.“Twelve years ago, before she and Larry bought the property, Liv had asked the owners if the lemons were edible. She’d understood from childhood that the milky sap of oleanders was poisonous, and wondered if the poison might leach into the soil.” Even with the most sensitive of story lines, such as “Compact,” which deals with the impending cancer-driven loss of a sister, the oppressive weight of choices lies clearly in the background.“Gilda’s four children are old enough to vote, and have all, one after the other, found their own ways to disappoint or alarm her. Josh is living with the wrong woman, Jenny dating the wrong man, Lisa pursuing the wrong career—modelling—she’s pretty but what chance does she have? While Robin, her youngest, is in the wrong university—a three-hour drive away—and never answers when Gilda calls.”

The stories are brought to life by meticulous attention to detail. Aubrey’s writing excels at bringing vitality to small elements of lived lives, and the gestalt created by these montages can be astounding. In “What We Hold in Our Hands,” we find an eloquent articulation of the complex ambivalence for an absent father:

Ever since my father left us, I’d been trying to forget him, forget how remote he’d become when he was still at home, forget the way he used to tuck me into bed when I was small, answering the stream of questions I invented to make him linger by my side. Forget the way I used to help him in the garden, digging holes for the tomato and cucumber seedlings. He’d shown me how to tamp down the soil around them, how to stake plants when they grew bigger, how to pinch off the new growth between the established branches and the stalk.

A flood of sensory detail often creates an overall impression that could not be achieved by a more expository approach. Take, for instance, this reflection on being pregnant: “If she didn’t have this life inside her, these hormones making her weepy and vulnerable, she could be happy alone, writing her dissertation. But the larger the baby grows, the smaller she feels—a tiny woman with a belly out there. Staring down at its unavoidable roundness, she doesn’t notice the sparrows in the lilac bush until they flash in front of her. They seem to have burst from her belly like blackbirds from a pie.” (“Outside of Yourself”)

There are no heroes in these stories. I suppose we could use words like courageous or tough to describe them, but I believe that would miss Aubrey’s point. She gives us ordinary people, caught in the webs of their own choices, and a faithful portrait of the times in which we live.

—Tim Rogers