Reviews

Fiction Review by Susan Sanford Blades

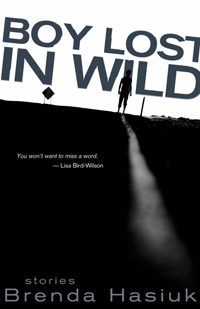

Brenda Hasiuk, Boy Lost in Wild (Winnipeg: Turnstone, 2014). Paperbound, 150 pp., $19.

In his homage to Winnipeg, “One Great City!,” John K. Samson of indie rock band The Weakerthans sings, “A darker grey is breaking through a lighter one.” The song, the refrain of which is “I hate Winnipeg,” is a heartfelt take on how many Canadians feel about their home towns, marked by equal parts love and hate. His description of Winnipeg’s grey, hopeless winter days, I’m sure, cuts to the heart of anyone who’s lived there.

In his homage to Winnipeg, “One Great City!,” John K. Samson of indie rock band The Weakerthans sings, “A darker grey is breaking through a lighter one.” The song, the refrain of which is “I hate Winnipeg,” is a heartfelt take on how many Canadians feel about their home towns, marked by equal parts love and hate. His description of Winnipeg’s grey, hopeless winter days, I’m sure, cuts to the heart of anyone who’s lived there.

In her third book of fiction but first book of short stories, Boy Lost in Wild, Brenda Hasiuk offers eight Winnipeg stories that ambitiously capture aspects of the city. Hasiuk embodies a unique voice in every story and it is clear she has done her research, both in terms of character psychology and in representing a wide array of Winnipeg’s inhabitants, from a young First Nations boy giving a speech as poster boy for a local youth shelter, to a Chinese exchange student tormented by a screaming neighbour, an inattentive landlord and some local punks, to a family of Indian immigrants dealing with the regrets of their lovelorn father and their track-star son’s possible cancerous tumour—even including characters from the city’s abnormally large Icelandic population. In “Blood,” the author shows us how a young autistic man experiences language, and artfully conveys his strained relationship with his mother. “Dad was a ’71 Camaro, steel blue, with worn sheepskin seat covers and its hood up.… Only the word mom remained imageless, was simply an everyday sound, like bang or pop.” In “Sandwich Artists,” she captures the inter-clique awkwardness that can happen between teenagers at their part-time jobs and the ease they feel when those social boundaries are removed, “Dorri and Casey speak of each other to no one, which gives an odd weightlessness, an unreality, to their conversations.”

Hasiuk begins each story with four or five facts, in a numbered list, that pertain to its content in some way or another (e.g., “Red hair is still honoured amongst Moslems, as the Prophet Mohammed himself was reported to have red hair”). While reading, I was unsure as to how I felt about this device. On one hand, the lists do serve as a unifying force in the collection and the facts are at times quirky and entertaining. On the other, it threw me off as the very first thing I saw upon opening the book; and the facts were not used to their full advantage. They could have, for instance, been incorporated within a story’s dialogue, employed as foreshadowing, or otherwise rounding out the story, but they were often peripheral and only distracted from it. They served as an explanation, a flashing red light that dictated “this is the theme of the story you are about to read.” I would have preferred the facts to be woven into each story and to come to them naturally. While each story presented a thoughtfully rendered section of Winnipeg life, a sense of cohesiveness seemed lacking throughout the collection. I found, upon finishing the book, I had been offered a cold, researched Winnipeg. What The Weakerthans could convey in that one grey line had no comparable effect here. I wished for Hasiuk’s mosaic of characters to be united by their feelings for the city, what it does for them, how they love and/or hate it, how living there has shaped them.

This collection was nonetheless enjoyable to read, and could be best encapsulated by its most accomplished story, “Life on Ice,” about a teenaged girl, Jasmine, who moves from her father’s home in Churchill to live with her Godfather in Winnipeg for a fresh start after committing an act of “truancy” at home. This story has many layers: a great voice, in-depth character insight (“What makes it worse, or maybe better, I don’t know, is that I’m convinced she loves me.… It’s just the day-to-day she can’t handle, the hands-on nuts and bolts of being there for someone”) and detail (“Frida wears the kind of sheer bras that let your nipples peek through. Ari smells like firewood and electrical tape”), as well as unique setting description (“The Japanese tourists always stood at the TV and giggled at the craziness of our parents circling in their ATVs, rifles at the ready in case a migrating bear on its way to the coastal ice decided to carry off a sugar-sticky little human”). As the story unfolds, its emotional weight evolves from being about a girl who feels abandoned by her mother to the inappropriate ways in which she reaches out for affection. Jasmine ends her tale with final words we can all—as writers and readers alike—relate to, “As usual, just writing these pointless words makes me feel better.”

—Susan Sanford Blades