Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Mitchell Parry

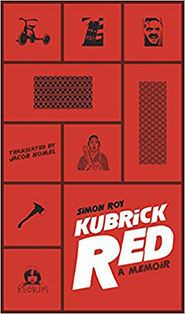

Simon Roy, Kubrick Red: A Memoir (Vancouver: Anvil, 2016). Paperbound, 160 pp., $18.

To begin, a terrible confession: despite studying and teaching film for about thirty years, I’ve never been a huge fan of the cinema of Stanley Kubrick. Heretical though it may sound, I often find his films, with their reliance on low-angle distance and one-point perspective, to be too coldly stylized, too detached for my tastes. Obviously, there’s much to admire in Kubrick’s work, but I have to admit I find it a very difficult corpus of films to warm to—especially those portentous, agonizingly airless late films featuring austerely lush settings populated by beings who seem less like characters than like faceless (though magnificently sculpted) ciphers moving from one centrally composed shot to another. Eyes Wide Shut, the last film Kubrick completed before his death in 1999, is probably the best example of this tendency, but it is an aesthetic that Kubrick embraced from A Clockwork Orange onward.

To begin, a terrible confession: despite studying and teaching film for about thirty years, I’ve never been a huge fan of the cinema of Stanley Kubrick. Heretical though it may sound, I often find his films, with their reliance on low-angle distance and one-point perspective, to be too coldly stylized, too detached for my tastes. Obviously, there’s much to admire in Kubrick’s work, but I have to admit I find it a very difficult corpus of films to warm to—especially those portentous, agonizingly airless late films featuring austerely lush settings populated by beings who seem less like characters than like faceless (though magnificently sculpted) ciphers moving from one centrally composed shot to another. Eyes Wide Shut, the last film Kubrick completed before his death in 1999, is probably the best example of this tendency, but it is an aesthetic that Kubrick embraced from A Clockwork Orange onward.

This isn’t to say I don’t like all of Kubrick’s films—even a heretic has to (however grudgingly) acknowledge some elements of orthodoxy. Dr. Strangelove is a brilliant and still relevant satire, and 2001: A Space Odyssey remains one of the greatest, most influential science-fiction films of all time; Barry Lyndon is a fascinating experiment in visual style disguised as a period piece. What remains especially compelling about Kubrick’s work is his ability to transform genre—the costume drama, the war film, the erotic thriller—into a decidedly personal statement of a world view. Perhaps surprisingly, no film in the director’s oeuvre reflects this auteurist quality than Kubrick’s 1980 foray into the horror genre, The Shining.

Montreal literature professor Simon Roy’s first book, Kubrick Red: A Memoir, is an often-harrowing account of the author’s family history as projected through the filter of Kubrick’s treatment of the source novel by Stephen King. The various, labyrinthine iterations of the narrative are important here: this is a book that attempts to translate the psychic impact of a film that attempts to translate a book’s translation of psychic disorder into prose (and it’s worth mentioning that King was outraged by Kubrick’s handling of the story). Roy’s connection to the film is singular and striking: stumbling upon the film (in its French version) on TV one Saturday night, the young Roy is shaken by a scene in which Scatman Crothers’s Dick Hallorann, chef at the Overlook Hotel, telepathically offers young Danny Torrance a bowl of ice cream. The seemingly innocuous scene terrifies Roy: “For some unknown reason, even though I couldn’t possibly be that naïve at that age, I felt like Hallorann had for a moment drawn back from his role as the guide to the Overlook Hotel to establish a direct relationship with me and reveal something hidden. A revelation that went far beyond a cordial invitation to savour a bowl of chocolate ice cream.”

Roy claims that, “Through The Shining, horror entered my life. A life which had, until then, been safeguarded by a mother always ready to overprotect me from the threats of the outside world.” From this imagined conversation with Hallorann emerges a sense of connection to the film—an obsessive fascination that at first is inexplicable (why thisfilm instead of another?). As the memoir progresses, however, we come to realize that The Shining’s visual narrative of blood-soaked horror has a deep, even traumatic personal significance for Roy and awakens memories of real-life family tragedies involving derangement, brutal murder, and suicide. Ultimately, the book takes on the form of a fifty-two-chapter maze, at the centre of which resides Danielle, the author’s mother, and her struggles against demons inner and outer, present and past.

Translating the written word into film is a notoriously complex task, how much more difficult, then, to translate the filmic image into text—and in the form of memoir, rather than as a novelistic re-telling. In many ways, though, Roy has chosen the perfect film for such an act: The Shining has a reputation for ambiguity, the kind of film that encourages multiple interpretations, including the extreme conspiracy theories outlined in the documentary Room 237 (Rodney Ascher, 2013). To his credit, Roy never indulges the compelling absurdities of that film, but still manages to let the book explore the many parallels and coincidences he finds between his family history and the narrative of The Shining—an endeavour Kubrick, who apparently loved coincidences, would surely admire.

Kubrick Red’s greatest strength lies in its structure, a series of very short chapters detailing the author’s relationship to The Shining, the production history of this and other Kubrick films, some of the bizarre theories about the film that have circulated over the years. Throughout, however, Roy returns to his mother, providing a loosely chronological narrative to hold the whole thing together. This allows the reader to experience the book as the textual embodiment of the Overlook Hotel; we weave through its chapters the way the film’s ghostly, unsettling Steadicam shots rush along the hotel’s corridors, drawn toward the shocking violence of Danielle’s childhood as inexorably as Jack Torrance and Kubrick’s camera are drawn to the horrors contained in room 237.

The book’s original French title—Ma vie rouge Kubrick (Les Éditions du Boréal, 2015)—offers a clearer sense of its subject than does the English translation, and this points to a relatively minor quibble: there are times when the translation, by Jacob Homel, seems to slip a bit. We learn, for example, that when Jack kills Hallorann “the old man crumbles [sic] to the floor.” More problematic (for me, at least) is the nagging sense that the book’s numbers don’t completely add up. Roy, born in 1968, claims he first saw the film when he was “ten or twelve, no more than that,” which means he either saw The Shining two years before it was released in theatres in 1980, or that it was first televised in Quebec the same year as its release. Otherwise, Kubrick Red is a fascinating and deeply moving account of one man’s attempt to make sense of his life, his family, and the film that has haunted both.

—Mitchell Parry