Reviews

Nonfiction Review by Candace Fertile

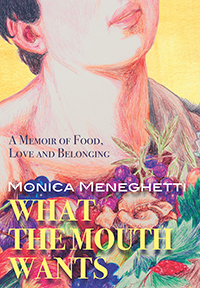

Monica Meneghetti, What the Mouth Wants: A Memoir of Food, Love and Belonging (Halfmoon Bay: Caitlin, 2017). Paperbound, 168 pp., $22.95.

“Tongues,” the first piece in Monica Meneghetti’s What the Mouth Wants, makes it clear that this memoir, a sensuous offering of variously sized verbal dishes, deals with what nourishes: food, sex, and love. As Meneghetti says, “Our first penetration is self-penetration with this soothing flange. And the thumb will be followed by air, by nipple, by milk, and from then on many things will enter our mouths, until our bodies cease to exist.” What makes existence bearable, or perhaps meaningful or even joyful, is a sense of belonging. And reaching that state can be arduous.

“Tongues,” the first piece in Monica Meneghetti’s What the Mouth Wants, makes it clear that this memoir, a sensuous offering of variously sized verbal dishes, deals with what nourishes: food, sex, and love. As Meneghetti says, “Our first penetration is self-penetration with this soothing flange. And the thumb will be followed by air, by nipple, by milk, and from then on many things will enter our mouths, until our bodies cease to exist.” What makes existence bearable, or perhaps meaningful or even joyful, is a sense of belonging. And reaching that state can be arduous.

Having grown up the youngest of three children in a traditional Italian family in Canada, Meneghetti had to cope with the challenges of the immigrant but, in her case, the challenges were compounded by the loss of her mother and her own bisexuality. That her mother’s death when Meneghetti was sixteen still affects her (and why wouldn’t it?) is evident from her dedication: “For my mom, l’ombra al mio fianco,” which means “the shadow by my side.” Loss has formed a baseline of existence, and the memoir grapples with the author’s desire to understand the gaps left by her mother’s absence and to assuage them with other relationships. Readers know right from the beginning that Meneghetti has been successful, as the Acknowledgements (placed immediately after the table of contents) pay tribute to her partners, sister, friends, mentors, teachers, publishers, and other writers. The journey to find her place in the world has been rewarded and, at age fifty, Meneghetti is deeply grateful to those who have helped her and to those who love her. She has created her own family, an unconventional one, but a successful and supportive one.

The book is divided into four sections: Antipasti, Primi, Secondi e Contorni, and Fruiti e Formaggi, and each section has at least nine vignettes, separately titled and very loosely following the trajectory of her life. But just as the courses in a meal play off each other, so do the vignettes, as Meneghetti plays with time and its effects. One of the longest pieces is “The Orchard,” and it details her mother’s death. She watches her father care for her mother and thinks about her parents’ fiery arguments in the past and how she had wondered if they were staying together until she left home. She remarks, “Now as I watch Dad caress Mom’s cheek and whisper something to her in Italian, I wonder if I understand what love really means.” She watches her aunt, who has come from Italy to be with her sister, and recounts how the sisters were raised during World War II in a convent near the Italian Alps, an experience that so scarred her mother that she never went to church. Meneghetti describes how her mother was the one who supported her desire to become a writer and always brought back notebooks from Italy for her daughter.

But her relationship with her father is less supportive. She leaves home against his wishes and, while she never fully explains the rift, it’s obvious that the pain lingered. Her father remarried, and for many years Meneghetti attended family Christmas gatherings. Finally, she just stops and has Christmas dinner with her chosen family, her long-term partners, Sheldon and Tasha. Both sound like remarkable people who are willing to share love and intimacy without feeling threatened, although, again, Meneghetti tends to shy away from much detail about their domestic life (apart from food).

Food—or the lack of it—plays a significant role in Meneghetti’s relationship with a boyfriend she meets in university residence, “a brainy, cycle-racing Adonis,” and with whom she lives for a while after graduation. Neither of them has any money, but the boyfriend, Toby, seems used to it and simply makes do. Meneghetti is always hungry until the night Toby serves her a marvellous salad, dripping with olive oil, and some bread. She loves it. She loves it, that is, until he says, “Tonight’s dinner, courtesy the Safeway dumpster. Can you believe they threw that stuff out?”

Overall, the book has many wonderful passages, some which focus on narrative and others that are musings less than a page long. For example, “Secret Ingredients” shows Meneghetti’s skill in including Italian words while exploring feelings: “Layered within smooth-as-skin pasta, the ragù of resentment mingles with the besciamella of abandonment. Melted mozzarella blankets lasagne like longing.” Longing may well be the overriding emotion of the entire book, and, as the longing is ultimately satisfied, the result is a sense of peace for both writer and reader.

Finding her place in the world means coming to terms with her sexuality, and while nowadays much is out in the open, we must remember it was not always that way, and people suffered (and still do suffer). In “The Pasta Machine,” Meneghetti describes making pasta with her parents and then combines that with a description of her father’s fury at her asymmetric haircut; then her father’s borsello, a small bag (which opens up a discussion of fashion and sexuality); then her own discovery of bisexuality at sixteen, when she is given an article on her idol, David Bowie, and is thrilled and confused when she reads that he met his wife when they were “‘both dating the same man.’” As she notes, “I didn’t understand why it was so utterly fascinating. It was the first time I’d ever been exposed to the concept of bisexuality.”

While I wished for more coherence in the memoir, I think Meneghetti has tackled some personal and cultural issues of great importance. And I suggest that the book be read as it is written—in small bits. It’s worth it.

—Candace Fertile