Reviews

Poetry Review by Rebecca Geleyn

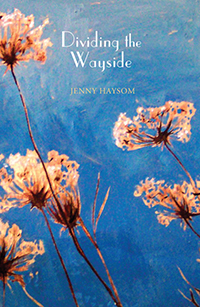

Jenny Haysom, Dividing the Wayside (Windsor: Palimpsest, 2018). Paperbound, 86 pp., $18.95.

Jenny Haysom’s debut collection Dividing the Wayside shows off her linguistic prowess while spanning a spectrum of themes. Playing on traditional forms such as the haiku and tightly rhyming couplets, Haysom also demonstrates an aptitude for looser, narrative-driven poems that meander in everyday life and memory tinged with melancholy. The collection opens with a stand-alone poem, “Unfastened,” that wakens the reader with vivid imagery and a hypervigilance towards the thrilling mechanics of objects: “the quick pleasure in zippers / realigning their tracks; and consider / Velcro biomimicking burrs.” Not only a wow-factor poem, “Unfastened” also conjures a meta-poetic (perhaps sarcastic?) sentiment about the collection as a whole: “If only there were / such utility in poetry.” The book is split into three sections following this opening. The first, “Something Between Us,” is a series of quiet familial poems, highly lyrical, deeply felt, and full of the past. The second section, “Angel of Repose,” approaches Emily Dickinson from different angles, with poems about her, written in her style, or engaging with Dickinsonian themes. The third section, “Stirring the Firmament,” is the most playful. In this part, Haysom bases poems on news headlines, current events, and flights of fancy for results that are both delightful and inspiring.

Jenny Haysom’s debut collection Dividing the Wayside shows off her linguistic prowess while spanning a spectrum of themes. Playing on traditional forms such as the haiku and tightly rhyming couplets, Haysom also demonstrates an aptitude for looser, narrative-driven poems that meander in everyday life and memory tinged with melancholy. The collection opens with a stand-alone poem, “Unfastened,” that wakens the reader with vivid imagery and a hypervigilance towards the thrilling mechanics of objects: “the quick pleasure in zippers / realigning their tracks; and consider / Velcro biomimicking burrs.” Not only a wow-factor poem, “Unfastened” also conjures a meta-poetic (perhaps sarcastic?) sentiment about the collection as a whole: “If only there were / such utility in poetry.” The book is split into three sections following this opening. The first, “Something Between Us,” is a series of quiet familial poems, highly lyrical, deeply felt, and full of the past. The second section, “Angel of Repose,” approaches Emily Dickinson from different angles, with poems about her, written in her style, or engaging with Dickinsonian themes. The third section, “Stirring the Firmament,” is the most playful. In this part, Haysom bases poems on news headlines, current events, and flights of fancy for results that are both delightful and inspiring.

Haysom’s poems make plenty of allusions, particularly to well-known Western authors (Donne, Poe, Woolf, Chaucer, Dickinson), so her collection will appeal to those familiar with canonical writing. Of particular note is her “Invitation to Elizabeth Bishop,” with its rhyming lines and perfectly placed refrain of “please come riding.” The poem’s last stanza exemplifies Haysom’s skill with both form and words:

And if you cannot come riding

come in writing,

a noonday ghost, a shadow on the page

inclining. Or with pails of blueberries

at your sides—though not for baking—

but for an afterlife’s supply

of the mystical, purplish

ink you’re formulating.

But the collection also assembles inter-texts with other objects and works of art, while notes at the end of the book provide the references. “Four postcards and an umbrella from the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam,” for example, is a series of ekphrastic poems that immediately invokes the artist’s style. “Toward the Blue Peninsula” wraps up the short series of poems after Dickinson and is based on a box made by Joseph Cornell, which in turn refers to a Dickinson poem. This poem is striking for its uncommitted wavering between interpretations, its struggle for definitive meaning reminiscent of the lament about poetry in the collection’s opening piece. The box is a “perch ready for the bird to come. / All we can do is anticipate— // though perhaps it’s been / and gone.” The poem is full of doubtful “or’s”: the box is again “Like a thought in an empty room. / Or a room—emptied— / so we can think.” It is in this uncertainty of knowledge that Haysom’s metaphors proliferate and where her poetry finds its strength.

Open endings are also a favourite, and these leave the reader teetering on an edge of possibility. In the quippy “Arrhythmia,” a single image of a starling flits across the page in the form of a question, beginning with an interlocutor asking her listener if she remembers the bird that flew in then out of the room “in a puff of Victorian soot / like the panicked / heart of Poe?” The question mark, though maybe expected, still startles, as the starling did. The ending of “Sized,” which traces a familial line through a grandmother’s ring that requires resizing, also ends with a twist of the poem’s meaning. The poet’s mother, she states, was “born blue, but named / Barbara— / which means ‘stranger.’” These final lines replace the warmth of the piece with a sudden chill.

Besides these terrific turns, Haysom’s strength also lies in her exceptional attention to detail in pictures, objects, and the natural world. This focus sets up metaphors so clear they strike with scientific precision. In “Dashes,” a jaunty exploration of the punctuation mark, Haysom calls these “logs for crossing / boggy spots or high wires / between stars—” and later “ladders / disassembled— / they’re intersections.” The poem continues like this, leaping from one vivid image to the next. “Unearthed” provides an intense curiosity, this time lingering on a beetle’s shell, which is

translucent

but tinted brown, like crackling Sellotape

unsticking from the spine of a yellowed

novel, and clinging to this, fine

crumbs of soil.

This investigative voice serves the collection well, as poems move from particular details to broader contexts—the unearthing of the beetle shell leads to the discovery of a cicada, “Basho’s / shell which had sung itself / utterly away.” The shift to Basho in “Unearthed” opens the entomological discussion up to history and poetry, a move both dizzying and satisfying. Haysom’s collection is playful and astute, an engaging read for both poets and a broader audience alike.

—Rebecca Geleyn