Reviews

Poetry Reviews by Will Johnson

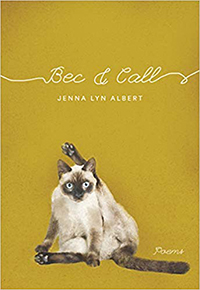

Jenna Lyn Albert, Bec & Call (Gibsons: Nightwood, 2018). Paperbound, 94 pp., $18.95.

Sandra Davies, Giacometti's Girl (Toronto: Cormorant, 2018). Paperbound, 88 pp., $18.

The sad-eyed cat on the cover of Jenna Lyn Albert’s Bec & Call is contorting itself into a vaguely sexual yoga pose, one leg hitched overhead, daring you to look at its crotch. This image perfectly captures the uncomfortable, subversive playfulness of her work. These poems force readers to confront ugliness while also mining dark moments for unexpected levity. “It’s not you, it’s the patriarchy,” her female narrator writes in “Deleted Dating Profile,” while in “The Rebound,” she sneaks out of a dude’s apartment “as subtly” as he “slipped the condom off mid-performance.”

The sad-eyed cat on the cover of Jenna Lyn Albert’s Bec & Call is contorting itself into a vaguely sexual yoga pose, one leg hitched overhead, daring you to look at its crotch. This image perfectly captures the uncomfortable, subversive playfulness of her work. These poems force readers to confront ugliness while also mining dark moments for unexpected levity. “It’s not you, it’s the patriarchy,” her female narrator writes in “Deleted Dating Profile,” while in “The Rebound,” she sneaks out of a dude’s apartment “as subtly” as he “slipped the condom off mid-performance.”

Albert’s work is deeply informed by the #MeToo movement, and routinely fixes on those moments when power shifts from abuser to victim, when her female narrator overcomes her subservience or complicity and embraces rage and retribution. In one of her more startling pieces, “Testament,” she writes about losing her virginity at fifteen to a Catholic schoolmate. Though “even he could see the hurry and the harm of such fervent fornication,” she still finds herself performing oral sex in the stairway outside the school theatre: “I wonder now if David hesitated before he severed Goliath’s head.”

One of Albert’s obvious strengths is wordplay. She tells an unwanted suitor “Yes, my lips are cabernet: sashay away,” then “I will drop you like Pluto’s relationship status: Solar. Sole. Single.” The title itself uses the French sense of “bec”—a kiss, mouthpiece, or beak—to complicate notions of compliance and submission. In “Tinder” the characters are “skittishly sipping local IPAs and disclosing our GPAs.” There are passages that beg to be read aloud, that could easily be spoken word, even rap. In “Deleted Dating Profile,” she makes her desires frankly known: “Netflix and lick my clit enough to warrant recompense.”

In one poem, Albert references the song “Chasing Waterfalls” by tlc, and it’s clear her narrator has taken their maxim to heart. She’s not waiting for a man to save her, and she’s not looking to be wedged into a narrowly defined gender role. She’s blunt about her Acadian upbringing, saying in “Famille” that she’s “the stuff of hand-me-downs in garbage bags” and, in “Quotidienne,” that she’s “Munsch’s mud puddle heroine.” Over the course of the book the character achieves a sort of self-actualization made possible by being abundantly raw and honest, not only about her past experiences but also about her complex desires as a woman and her stubborn insistence on living the child-free life of an artist.

In Giacometti’s Girl by Sandra Davies, her narrators endure tragedies great and small: in “What’s been and lost,” a husband with young sons shoots himself in the skull; in “Without a Script,” an elderly mother struggles hopelessly with dementia; and in “Remembrance Day,” a WWI veteran can’t leave behind the memories of trench life decades before. Sadness and turmoil are seen as inevitable; in her title piece Davies writes “we women sit braced, contained / hearts willed to steady / waiting with guarded eyes / for God’s other shoe.”

In Giacometti’s Girl by Sandra Davies, her narrators endure tragedies great and small: in “What’s been and lost,” a husband with young sons shoots himself in the skull; in “Without a Script,” an elderly mother struggles hopelessly with dementia; and in “Remembrance Day,” a WWI veteran can’t leave behind the memories of trench life decades before. Sadness and turmoil are seen as inevitable; in her title piece Davies writes “we women sit braced, contained / hearts willed to steady / waiting with guarded eyes / for God’s other shoe.”

Davies’ title refers to a print she purchased depicting one of the Swiss artist’s creations. The girl depicted sits on a grassy bank, arms crossed, waiting patiently for her life to happen. This image permeates the text, as the characters scrabble to find meaning in their mundanely hellish existence. She writes about listening to Chopin as a child: “the longing in each pearly note, / the undertone of deep accepting sadness / conspiring … to carry us / to safe untroubled sleep” (“Nocturne”). These moments of catharsis, these glimpses at a supernatural reality beyond our comprehension, are the spiritually rich experiences Davies is most interested in having us witness with her.

If this is a book of questions, then Davies goes to every available length in search of answers, asking readers to envision the grandiosity of the cosmos and then ponder the dream-life of a child in utero. She wonders about the tiny suns of the N11 Nebula: “do they too bask, / soothed by rhythms of the Mother’s deep / humming? Is there nurture in fire and dust, the swirling hot winds?” (“Tiny Suns”). In grief, her characters look to God, to science, to any available justification for why suffering exists, and sometimes find solace in peculiar moments. In her nine-part poem about her husband’s suicide, her emotional catharsis comes while playing with her grandchild: “She laughs, this girl, / head thrown back, / mouth wide open / to drink in her delight. / Straight from the belly, she laughs / and laughs. And here you are.”

Though this collection routinely veers into dark territory, it’s not wholly morose. In “Farm Wife’s Tale,” we get a comedic meeting with the Messiah: “This Jesus looked a lot like that nice doctor / who came to the farm when Tom was sick / with the sugar diabetes.” She also takes us to unexpected places, as when she writes about Benazir Bhutto, the first woman to head a democratic government in a Muslim-majority nation, and Prime Minister to Pakistan in the 1980s and ’90s. She finds through-lines that draw a multitude of threads together, every poem circling back to the same themes of death and transcendence. As her mother’s condition worsens in “Without a Script,” Davies writes “she’s dying, even / enjoying it somewhat, the drama—we’re more alike than either of us cares to say.”

—Will Johnson