Reviews

Fiction Review by Kyra Kristmanson

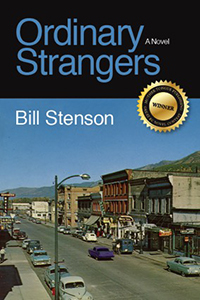

Bill Stenson, Ordinary Strangers (Salt Spring Island: Mother Tongue, 2018). Paperbound, 274 pp., $23.95.

Most families are made, but some are found. For Sage and Della Howard, family begins with a child abduction in the woods outside Hope, B.C. Bill Stenson’s novel Ordinary Strangers explores family dynamics in uncharted territory after a childless couple seizes their opportunity to start a family when they happen across an abandoned toddler in searching for their lost dog. Della wants to be a mother, and names the girl Stacey Emerald Howard. Sage is apprehensive, but “once the Howards invested in a winter coat, they no longer mentioned finding the authorities and returning the girl to wherever she had come from.” This unusual dynamic weaves through a web of the mundane as the Howards’ lives unfold.

Most families are made, but some are found. For Sage and Della Howard, family begins with a child abduction in the woods outside Hope, B.C. Bill Stenson’s novel Ordinary Strangers explores family dynamics in uncharted territory after a childless couple seizes their opportunity to start a family when they happen across an abandoned toddler in searching for their lost dog. Della wants to be a mother, and names the girl Stacey Emerald Howard. Sage is apprehensive, but “once the Howards invested in a winter coat, they no longer mentioned finding the authorities and returning the girl to wherever she had come from.” This unusual dynamic weaves through a web of the mundane as the Howards’ lives unfold.

The narrative occupies a moral grey area almost entirely throughout. A child, taken with no one to notice, is raised in a loving home in the best way Della can manage. Sage’s brooding moods and erratic behaviour put the family in jeopardy several times over, but he provides for his family no matter what. Stark contrasts like these coexist so closely in character dynamics that the entire narrative contains an edge of discomfort. It becomes almost impossible to parse out despicable realities from moments of perfect tenderness, like a lovely family Christmas that ends with the image of a pearl necklace, meant for Sage’s mistress, sinking to the bottom of a river.

Stenson plays with irony, adding a dry side-glancing humour to offer respite from more morose or disturbing themes. A destroyed snow fort devastates young Stacey, and casts Sage and Della’s judgmental eyes on someone we might consider a real mother. When Stacey wanders home from kindergarten and her absence is unnoticed upon her marched return, a frantic Della catastrophizes the way any parent would: what if someone had taken her? These moments remind the reader of Della’s almost delusional commitment to her role, while also showing a genuine love and concern for her daughter, and further muddle our outsider perspective on the dynamic as a whole.

Stenson, born in Nelson, B.C., clearly knows the terrain of the story’s setting. The brutal honesty with which he writes about the area requires a level of deep intimacy. His delicately crafted descriptions give a sense of the small-town west known to many Canadians. Swaddled by rivers and mountains and isolated from the big world outside, Fernie feels much like my northern-B.C. hometown, the Howards’ life there accented by piling snow and icy roads that keep families sealed behind closed doors through the long winter months. In spring, the world comes alive; in summer you do anything to get out of town—away from the hot concrete—and autumn dies into winter again. We watch each other grow up and grow older, and eventually fade away. We admire those who get out.

A shift in focus occurs at the novel’s midpoint, away from family values to a series of tragedies and a blossoming of awareness in an adolescent Stacey. A traumatic misunderstanding reveals past transgressions in close quarters, and the family that Della worked so hard to fabricate is torn apart. The narrative comes full circle from one form of abandonment to another, leaving Stacey with a lifetime of hard lessons in her sixteen years, and some difficult choices regarding how to express her new-found agency. Here Stenson illustrates the line we draw for family—constantly moving it further back, little by little, each offence forgiven. At what point do we lay down the hard line?

Stenson’s novel asks us to consider one key question: who are we to judge what a family is? The answer is unclear, even at the last lines of a hopeful ending. One could say this was a family forced into existence by selfish and questionable actions. Whether our bonds are of blood or something else, individuals must define their own relationships. Stacey is left with this burden at the close, and we are left to wonder how we might begin to define things differently for ourselves.

—Kyra Kristmanson