In the “New World” the colonial

administrations had different social conditions to work with when

engaging the surveying of “new”

territory. As Scott argues:

Where the colony was a thinly populated settler-colony, as in North

America or Australia, the obstacles to a thorough, uniform cadastral

grid were minimal. There it was a question less of mapping preexisting

patterns of land use than of surveying parcels of land that would be given

or sold to new arrivals from Europe and of ignoring indigenous peoples

and their common-property regimes. (Scott 49)

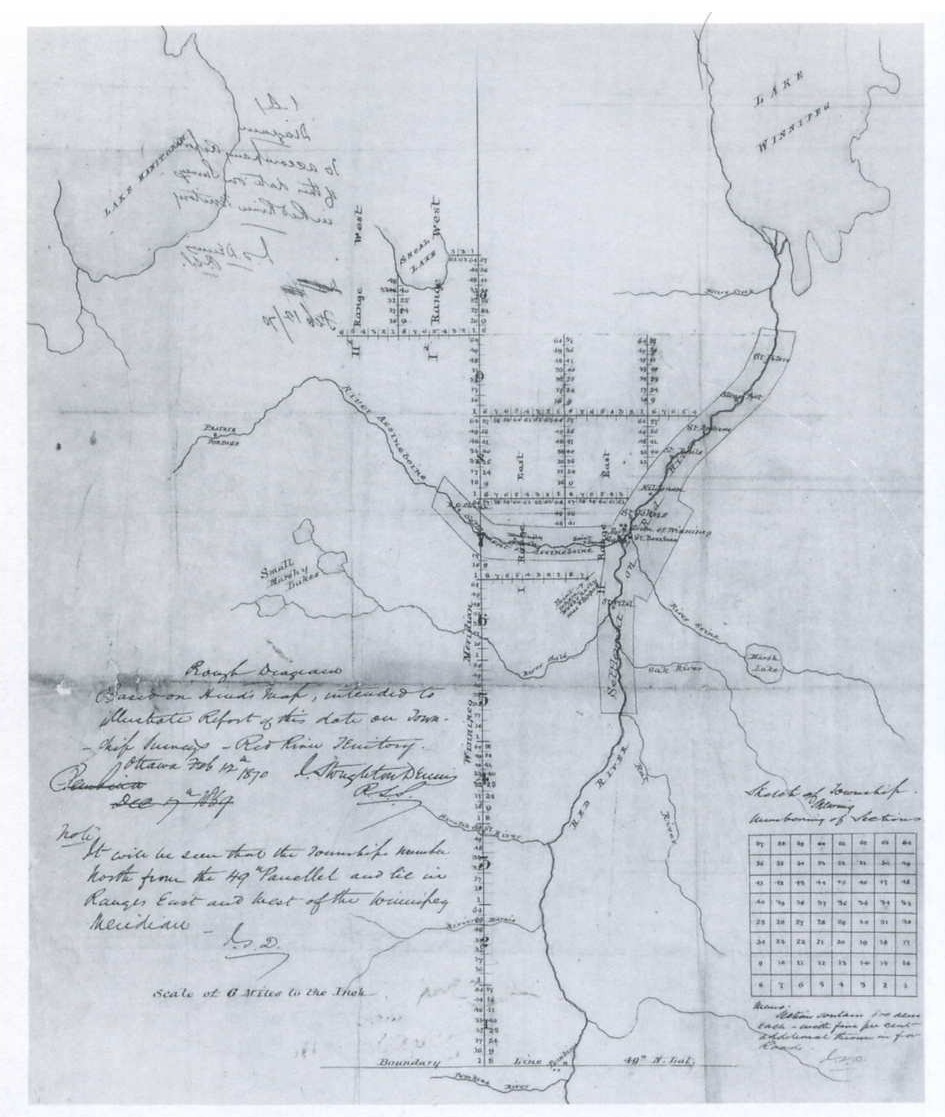

Map of Early Winnipeg

|

In

mapping out new territory, “British” systems of land

holding were often promoted as the desirable forms of settlement. Pat

Moloney shows that “salesmen of colonialization” (Moloney

34), such as Edward Gibbon Wakefield, promoted systems of drawing in

settlers and organizing them on the land as a “systemic”

process (Moloney 35). The Wakefield system’s goal was to

create a productive society that would be based upon not only the

“cultivation of fertile ‘wastelands’ but also the

cultivation of tastes, wants and desires” (Moloney 36).

For Wakefield one way for the promotion and maintenance of Victorian

cultural values in the colonial setting was to offer land, as Moloney

states, “at a uniform price in an organized and equitable way

with the government providing security of title" (Moloney 35).

Thus the state was to have a heavy role in the promotion and

organization of settlement. To accomplish this state officials

would need, as a prerequisite, a firm understanding and knowledge of

the territory they wished to settle. Cadastral mapping provided that

state knowledge.

|

Surveying and Cadastral Mapping in Colonial British Columbia

Cole Harris has provided two examples of how surveying and mapping were

used in British Columbia as tools for the

administration of territory by

the British. The first way in which cadastral mapping and surveying

were used is primarily concerned

with the practicality of securing title to land. For property to be

owned it had to have a specific location, boundaries

and boarders. Maps fulfilled this requirement and were thus a

fundamental aspect of the acquisition of land in a colonial setting

such as west coast (Harris 175).

The second aspect of how colonialism used mapping is related to how

mapping was used to help influence the perception, or using

Scott’s terminology, the “legibility” of a colonial

space for cultural and political means. Harris argues that, “maps

conceptualized unfamiliar space in Eurocentric terms, situating it

within a culture of vision, measurement, and management” (Harris

175). Harris argues that the creation of cadastral maps

re-oriented the colonial administrator/settler’s perception of

space by providing maps as a way to conceive the acquired territory in

a new spatial dimension. Not only did this re-orientation of conceiving

space graft upon the landscape a system that reinforced European

conceptions of property relations, typified by the cadastral

system’s use of grids and carefully measured and numbered parcels

of land, but the cadastral system also enabled settlers to use their

own methods of conceptualizing and administrating space as a way to

replace aboriginal ways of knowing and using the land (Harris 175).

In Harris’ own words, “this cartography introduced a

geographical imaginary that ignored indigenous ways of knowing and

recording space, ways that settlers could not imagine and did not need

as soon as their maps reoriented them after their own fashion”

(Harris 175) Scott is more direct in arguing the same point when

he quotes Kain and Baigent:

The cadastral map is an instrument of control which both reflects

and consolidates the power of those who commission it…the

cadastral map is active: in portraying one reality, as in the settlement

of the new world or in India, it helps obliterate the old. (In Scott 47)

Both Kain/Baigent and Harris’ statements reinforce one of the

prime directives of the Wakefield system, namely, the cultivation of

tastes, wants, and desires; specifically the desire to impose a

European way of looking at, and thus experiencing, the colonial setting.