Reviews

Fiction Review by Corinna Chong

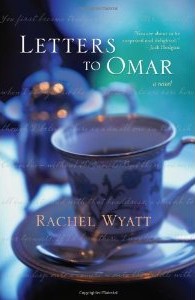

Rachel Wyatt, Letters to Omar (Regina: Coteau, 2010). Paperbound, 256 pp., $21.

It’s a charity dinner. The venue is a grungy, abandoned building, the main course is goat bought on sale, and the Three Elderly Women with a Purpose (acronym: TEWP) responsible for organizing it all are still in the midst of discovering what their purpose really is. Dorothy and Kate, cousins by blood, and their long-time friend, Elsie, are “sisters in the combat of life” who have seen each other through the trials of child-rearing, failed marriages, and growing old. An affront to the stereotypes of women over seventy, they are independent, computersavvy, ambitious, and energetic women who crave sex and adventure, and viciously reject stagnancy. When Kate’s grandson, Jake, suddenly decides to ship off to war-torn Afghanistan and deliver help to the needy, the “trinity,” headed by tenacious Dorothy, seek to make an impact by starting a fundraising initiative in support of a poor Afghani village. For Dorothy, the charity dinner is also about absolution, for it was her own advice that persuaded Jake to volunteer himself for the dangerous mission, much to the silent resentment of Kate and her daughter, Delphine (Jake’s mother).

Haunted by the ever-looming threat that Jake’s journey may drastically change him or even claim his life, the loved ones left behind begin to navigate uncharted territories of their own, sparking unexpected romances and family melodrama. Wyatt weaves a complex web of familial relationships that places a heavy focus on women: childless Dorothy plays “aunt” to Kate’s and Elsie’s children and grandchildren, who include Delphine, Jake, and Elsie’s daughters, Isabel and Alice (or Alec, as she prefers to be called since coming out as a lesbian), as well as Alec’s estranged daughter, Elvira. The events of the novel unfold from the alternating perspectives of Dorothy, Kate, Delphine, Elsie, and Isabel, showcasing Wyatt’s adeptness for building dramatic irony through fragmented narrative. While the themes are serious, Wyatt’s light-hearted tone lends an air of comedy and farce to even the gravest of situations, never allowing the novel to slip into a dismal slump. For example, in one of Dorothy’s musings, she considers how “she’d come to know more loneliness than ever before. She understood those works of art in which human figures hung suspended in space, or were isolated in a crowd. The one grey person in a mass of people in bright clothes. She’d seen a picture of a Roman tomb with images of the faceless dead… Come on, Dorothy, stop maundering and make yourself a cheese sandwich! What was it about that sharp-tasting fatty food that was so cheering?”

Wyatt’s effort to give a distinctive personality to each character in her multi-generational cast is at times thwarted by the consistency and control of her narrative voice, but at the forefront is Dorothy, chronic inquisitor and compulsive letter-writer. Dorothy’s “one-way correspondence” with public figures like Queen Elizabeth, Ronald Reagan, and Oprah Winfrey has, over the years, become her outlet of self-reflection—a way in which she can work through her personal dilemmas in the process. The pieces of these letters, which are interspersed throughout Dorothy’s narrative, offer some of the novel’s most insightful passages. “Dear Mr. Chamberlain,” she writes, “I don’t recall hearing your voice telling Britain that it was ‘now at war’ in September 1939 but […] I grew up knowing who you were and what you had done. I think you were a man who hoped. You were blinded by hope and couldn’t see evil when it was staring you in the face. If you were alive now, you might have found your niche.”

The addressee of Dorothy’s latest letters is Omar Sharif, the enigmatic star of the 1960s-era films Lawrence of Arabia and Dr. Zhivago. “You first became truly exotic to me,” Dorothy writes, “when I saw you in the desert. [...] there you were all in white, and with that headdress; a sheikh to your toenails. If I’d have been there, I would have leapt—can you leap onto a camel?—onto the saddle with you.” In his roles as a charismatic Chieftain in the Arabian Desert and a lovecrossed battlefield doctor for the Imperial Russian Army, Omar is Dorothy’s ideal man, at once a manifestation of her unreachable fantasies and a conduit for her idealized version of Jake as a brave crusader, immune to danger. However, the real Omar Sharif—the one with grey hair, wrinkles, and a spotty reputation for womanizing and gambling problems—mirrors Dorothy’s waning faith in her aging self as she wonders, “what earthly use he was to anybody anymore. How had he dared to become this aging version of the handsome young doctor who’d rattled along in the train across Russia? Was he now simply a total waste of space?”

Dorothy, Kate, and Elsie all find themselves up against the maddening reality that “people don’t always see older women. They look right past us. We get ignored.” Though their fundraising affair never measures up to Dorothy’s grandiose imaginings, it becomes a way for the three women to reflect upon the past, rediscover the possibility of second chances, and prove their worth to the people who matter most. At its heart, Dorothy’s true objective is a humble one: “I have not been entirely good through my life but I am now, before the end comes, trying to be useful.”

Although Letters to Omar does not front any new literary territory, it does manage to integrate gripping plot twists, sharp and funny dialogue, and elegant moments of contemplation in its exploration of the lives of seven women, each searching for a sense of self while striving to bring together the threads of family. As Dorothy discovers through looking back on the unlikely events of her life, “there are glints of gold. Glints of gold.”

—Corinna Chong