Reviews

Fiction Review by Aaron Shepard

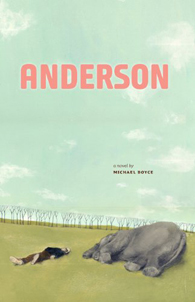

Michael Boyce, Anderson (Toronto: Pedlar, 2010). Paperbound, 228 pp., $21.

Anderson, computer technician by day, “detective of the soul” by night, is a descendent of the post-modern, metaphysical sleuths imagined by Auster, Borges, Bolano, or Robbe-Grillet: a vodka-sipping philosopher extraordinaire chasing ghosts, “detecting in the strangeness.” As a

novel, though, Anderson owes a much deeper debt to Gertrude Stein or Camus. The writing, as Larissa Lai describes it on the back cover , is a remake of “urban realism, 1930s fatale-noir and dark fantasy.” This conscious aping and blending of eclectic styles yields unique rewards for the reader, even as it poses certain hazards for the author.

When a strange poem written on a bathroom stall presents a new mystery to solve, Anderson is lured to Half Moon Aether Night at a small nightclub called The Belly. There, he spends his time detecting “energies” and trying to stay sober. His sleuthing techniques are, he admits, exceptionally passive: “He just sits back, so to speak, and observes the spin his mind is in.” Anderson is a detective of the mundane as well as the metaphysical, endlessly riffing on the minutiae of a slacker existence. This can be perilous: a character’s choices, not his observations, are what give a novel its momentum and lift. The obsessive interiority of the voice often yields abstract and expository prose. Even when we meet the object of his search—Ella, a seductive young woman seemingly possessed by a malevolent spirit—the moment feels underwhelming because we witness her strange “blathering” from a distance. Ultimately, it is the author who best states the risk: “He is in jeopardy of letting too much time slip by in idle musing.”

Luckily, Anderson’s situation feels more immediate once he begins to suffer from blackouts, strange dreams, and large chunks of lost time. His character is further grounded through interactions with Ella and two other characters integral to his case: Jones, a quiet and lovelorn magician; and Jack, who becomes a sort of ally. Eventually, Ella’s ghost possesses him entirely and, disembodied, Anderson must fight to regain his corporeal form. Here at last, he is forced into action.

Ella passes on her ghost through sexual and magical means, which create some wonderful metaphorical possibilities. In fact, much of the novel is a dizzying meditation on the nature of ghosts, the lingering energies of broken relationships, and people haunted by their sexual past. Treading the hazardous terrain of excessive philosophizing, the reader is rewarded with moments of dark-humoured revelation: “But even when they are apart from their beloved automobiles, people on the sidewalks still behave like cars, because of traffic-mind, which is the residual consciousness derived from being one with cars.”

The story is told from a third-person point of view, but the narrative voice achieves a remarkable, nearly flawless intimacy with the protagonist. There’s ample evidence of a skilled, intelligent writer at work, which makes some choices puzzling, as when Boyce relies on f-bombs and multiple exclamation marks to convey dramatic tension: “Then Anderson screams into its ear, GET THE FUCK OUT!!....Ella screams, What the fuck is going on?!!!” Comic irony? And if so, to what purpose? The author’s intent—that is, his relationship with the characters and the reader—is a greater mystery than the haunted girl’s ghost. For example, Anderson contemplates the detective/femme fatale dynamic he finds himself positioned within and begins to deconstruct

it: “But Anderson is not like those detectives in the classic film noir stories.” However, the clichéd dynamic of the detective/femme fatale was never firmly established prior to the deconstruction. The conventions or motifs of the film noir genre should be concretely present and active as a framework in the story, allowing the reader to engage or participate in the text in the expectation of having those conventions subverted. It is difficult to subvert what is hardly there.

Anderson is a comic sort of outsider, not unlike Meurseault in Camus’ L’Étranger or Mathieu in Sartre’s Age of Reason—seeking intimacy, yet unflappably confident in his own identity, his distance from the world. Is he a true detective of “the strangeness,” whose work is as necessary to the world as he believes? Or a deluded young man caught in an existential nightmare? Boyce shrewdly conceals his hand, never pulling the curtain away from Anderson’s rambling mind. Perhaps this is enough. For all the potential pitfalls, the overall effect of the Stein-like wordplay and underlying irony make this novel an original and compelling work. Written with an artistic, almost punk sensibility that feels defiantly anti-CanLit, Anderson seems destined for a cult following, to be savoured.

—Aaron Shepard