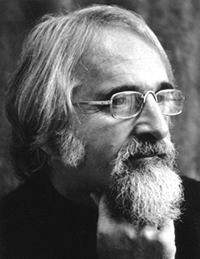

That Momentary Peace Which is the Poem: Matt Thibeault in Conversation with Gary Geddes

Malahat intern Matthew Thibeault talks with Gary Geddes about his Long Poem Prize winning piece, “The Resumption of Play,” as well as his narrative process and the role of the writer.

See the original announcement page for the 2015 Long Poem Prize winners.

You’re known as a writer who takes on social and political issues. What prompted you to write “The Resumption of Play”?

I’ve been working for several years on a book about Indigenous health issues, in particular the segregated Indian hospitals, their painful legacy and their links to the infamous residential schools. As I read widely and interviewed elders across the country, I kept hearing comments about the residential schools that troubled me and that would not likely find a place in my non-fiction work-in-progress. Gradually, these fragments coalesced and I found myself in verboten territory yet again, that place avoided by the angels, but so often trod by foolish poets. Although I knew I might end up looking like St. Sebastian, when the critical arrows begin to fly, or like someone who’s tangled with a porcupine, I thought: Hell, I’ve spent my life writing persona poems about ancient terracotta warriors, the Spanish conquest of the America, Chile during the dictatorship, Trotsky on the morning of his assassination, the so-called mad bomber of the House of Commons, ironworkers who survived (or did not) the collapse of the Second Narrows Bridge in Vancouver, POWs in Japanese prison camps in Hong Kong. The list could go on.

Was there something different about this persona poem? I wondered. Yes, as a white man, I am clearly part of the problem, writing from a position of privilege and power. I tried re-writing the poem addressing this issue, but it did not work; the intimacy and power were lost and the revision became about me and my struggles to write about a First Nations boy. In short, a postmodern mish-mash. This poem, I thought, is not for Indigenous people, who know these stories all too well, but for the rest of us who have too long hung on Lester B. Pearson’s Nobel Peace Prize, thinking of ourselves as gentle people, innocents on the world stage, and Canada as number one destination for immigrants. Our history is brutal. Canada is the world’s largest land-grab and our treatment of the original inhabitants constitutes a genocide in slow motion. All this blather, of course, I could not put in the poem, which had to be personal, intimate, concrete and rendered, as Sartre suggests, with “an essential lightness.”

Did you know you would write an 18-page poem when you started? Do some themes feel long and others feel short? How do you know and how does it affect your process?

I started to write this poem when a voice came to me, took me by the throat and said: Tell my story! To honour that voice, I had to listen to its inner promptings, imagine the separation anxiety of the child, the brutal awakenings in store, the crisis of identity that came from being abused and told that you and your culture are worth nothing, the flight from pain and the descent into hell that are to be found in alcohol, and the constant, almost impossible dream of recovery. The process here was not unlike the writing of The Terracotta Army; in fact, those individual poems came out as nine couplets, military in their appearance and restraint, 18 lines, a sort of Chinese version of the sonnet, roomier but still tight. In “The Resumption of Play,” I felt the individual pieces needed a similar kind of restraint, so I stuck with the eighteen lines but used three six-line stanzas instead.

The process reminds me of Dylan Thomas’s moving account of his creative process, where he had to fight alcoholism and other demons: “Out of the inevitable conflict of images,” he wrote, “—inevitable because of the creative, destructive and contradictory nature of the motivating centre, the womb of war—I try to make that momentary peace which is the poem.” The peace poetry affords is not permanent; it’s no more enduring than the peace afforded to Ethiopians and Eritreans, or to Israelis and Palestinians. It needs to be re-negotiated daily. Like peace, poetry is a process, a way of life, a daily discipline of self-assessment and commitment and renewal, driven by good faith. Not an easy task, because language, like politics, is an unstable medium; it’s dirty with sound, with secondary meanings and with unexpected connotations that come zinging in from the side to torpedo the best of intentions.

About length, I am never sure where an image or a persona will take me. I try to keep myself open to new ideas, new depths, going down, as Yeats suggests to the “rag-and-bone shop of the heart.” The long poem takes time, and encourages the taking of time; it also has the advantage of letting the unconscious provide unexpected surprises, day to day. I seldom know when a poem is finished; in fact, the revision never stops for me, even after publication, or in the middle of a poetry reading. As Paul Valéry said: “A poem is never finished, only abandoned.”

“The Resumption of Play” tells the true story of tens of thousands of people. You’ve created a single character to represent them all and reflect on his life in vivid detail. Often we plant little pieces of our own stories in our characters in order to make them truly occupy historical space. Are there any places in this poem where you think you may have done so?

I like this question very much, and it’s one that I think about often. Flaubert once advised the novelist to be everywhere felt but nowhere seen in his work. I appreciate that advice and try to keep out of the story as much as possible. But I also realize that everything I write, however remote the persona might seem from my own experience, is informed by who I am, what I believe and what my gifts and limitations are as a writer and a human being. “Resumption” is no different. I know the meaning of shame, addictive impulses, personal failure, and the struggle to rise above my own weaknesses. Those are the emotional linkages that must be there if a character, a persona, is to feel authentic; but, of course, there are also those moments when a known experience from one’s own personal history feels as if it might be useful. So, in this long poem I ransack my experience as a young man working at B.C Sugar Refinery, as a former religious, my reservations about academia, and other experiences readers who know me might detect.

Poems like this spark conversations about issues like “The Role of the Writer.” What are your thoughts on what that role might be?

I’ve probably had too much to say about this already. Every writer has a different path to follow. Mine has involved a lot of writing about social breakdown, violence, war and individuals caught in the machinery of history. I would not recommend or wish this same path on anyone else. There is so much to be written about domesticity, the struggle to be a good person, a loving partner, a caring parent, and about the need to celebrate and stand in awe of the earth and its beauty. If I had another life...

Matt Thibeault

* * * * * * * *